BARBARA KRUGER

CAROL SQUIERS

When Barbara Kruger first showed her large text-and-image works in the early 1980s, no one could have predicted the enormous influence she would have, not only in the arts but in venues as diverse as Newsweek magazine and MTV. A committed feminist, she takes as her subjects the skewed social relations created by the inequalities of gender, class, and race. Always working in outsized scale—one of her favorite forms is the outdoor billboard—Kruger has in the last few years begun doing large installation works. Here she talks about projects she has done in an art gallery, a new subway, and on the grounds of a new museum building.

Carol Squiers: Your last two exhibitions in New York have been installations, but you’re also working on an installation in a different kind of venue in Strasbourg, France.

Barbara Kruger: It’s in the main subway station for a new underground line that’s being built in Strasbourg. I’ve been working on it since September 1992—and it’s supposed to be completed in November 1994. It was a terrific opportunity for me to do an installation—one that I didn’t have to pay for myself, first of all, and one that was permanent.

CS: How did it come about?

BK: I was chosen by a committee led by the European curator Jean-Christophe Ammann, who’s in Frankfurt now. He curated my first European show. I went to Strasbourg and had meetings with the town government, the transportation authority, and the architects. Talking to the architects was most important for me, looking at their sense of space and use of materials, which struck me as being so different from what architects use in this country. The varied choice of materials was interesting—colored glass, different kinds of stone. Architecture has a presence in Europe that it doesn’t have here.

CS: What are the components of the installation?

BK: The stairs leading to the platform each have a single word on them—play, live, die, love, hate. Up above the train it says, “Where are you going?” So every single day you think about that first question. There will be sixteen plaques inset into the platform at the entrance to each subway car, some with only words, others with images and words. I did research in Strasbourg because I wanted some of this to be historically based. I used parts of a really beautiful alphabet designed in the nineteenth century by a woman from Strasbourg, Mile. Hélène Scheffer, in which each letter incorporates drawn pictures of monuments and buildings in the city. I’ve written texts with the pronoun you on each of these; some are more tied to the image than others. There’s one picture of a cathedral, and the text for that is about looking up at the sky and thinking about your life and your death.

CS: How did you deal with the fact that people are in the subway when they’re looking at this?

BK: I wanted to talk about what it’s like being in that place waiting for that train, but also tie it into other things. You are late, you are tired, you are happy, you can’t stop smiling, you’re in love, you feel crazy, the world is spinning, you are dreaming. Kind of poetic but very tied to the everyday, things that you don’t usually see in a permanent installation that’s going to be there for hundreds of years.

CS: What about the big image and the words above the trains?

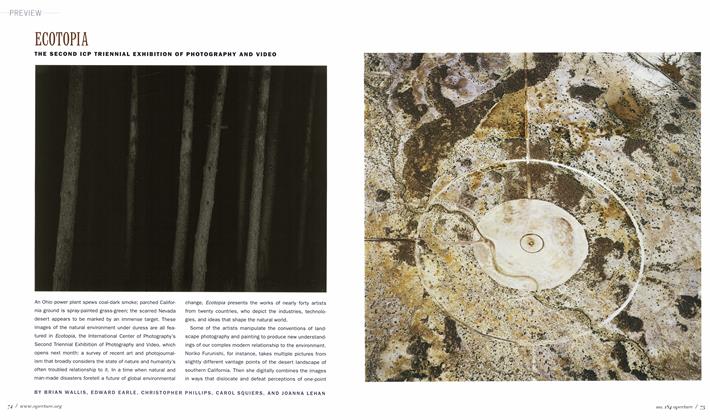

BK: There’s one huge silk-screened image on aluminum panels that covers two concrete beams and hovers over the station. The image is of a man with a trap-door in his head, and the words across it read, “Empathy can change the world” in French. The other twelve beams have questions sandblasted into them, so they’re very subtle. The questions are the ones I’m continuously asking—“Who speaks,” “Who is silent,” “Who prefers questions to answers,” “Who dies first,” “Who laughs last,” “Who salutes the longest,” “Who prays loudest,” “Who is beyond the law,” “Who will write the history of tears.” You have to look up high over your head to see them.

CS: Does Strasbourg have a broadly multicultural population?

BK: Increasingly it does. Many of the questions address notions of national identity and the idea of empathy: putting yourself in someone else’s position to change things a little bit. To use “Empathy can change the world” has to do with the questions of allowance, thinking about difference. There are different ways to make an impact on people’s psyches. One of the panel images is of a hospital. I talk about living and dying, and thinking about your birth and trying not to think of your death. It touches you in very forthright language.

CS: How do you feel about the project after two years of long-distance work on it?

BK: To me this was an incredible opportunity to work on a really large scale, dealing with an enveloping environment in a way that I certainly could never afford to do on my own. It was also a chance to work in a truly dense and well-used public space where ideas about pleasure, oppression, nationality, empathy, fear, memory, love, and history could all be addressed by using the conventions of public signage.

CS: Why did you decide to do an installation, rather than individual pieces, for the second time in a row for your exhibition at Mary Boone Gallery last March?

BK: I like the way an installation can envelop the space and have a greater impact on the viewer. In this piece, I liked using the idea of the crowd; and the sound track was really important. I felt comfortable working with sound after doing a number of radio spots for the Liz Claiborne anti-domestic-violence campaign and television spots for MTV.

CS: What was your overriding conception for this installation?

BK: The same overriding conceptions that motor all my work: power, love, hate, sex, death. And then I thought about power and crowds and what happens during a religious service or at a sports stadium or when large groups of people get together. I wanted the speaker on the audio track to have the ability to rile people, to see how that posture is abused, how it appeals to people’s worst instincts, their worst fears, their hate and their contempt.

CS: Talk about the images you used.

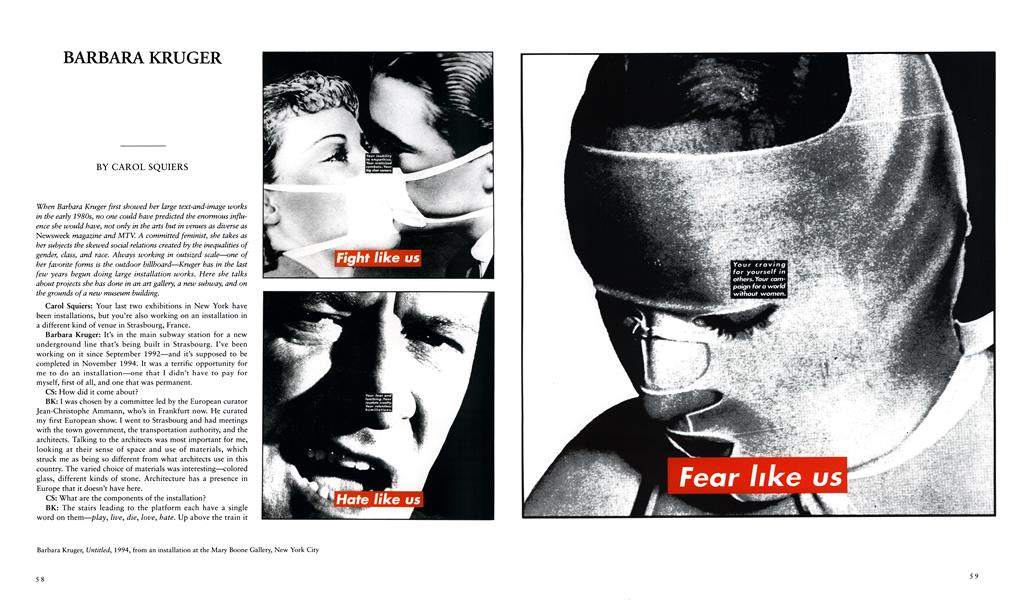

BK: The big image, which covered the gallery walls, was one of a crowd. There were nine images with statements inset into the crowd: “Pray like us”; “Believe like us”; “Think like us”; “Fight like us”; “Hate like us”; “Talk like us,” etc. Then there were small texts in the middle of the panels, above the statements—not to illustrate them literally, but images that were suggestive of that command. For “Believe like us” it was a man with a bible and a snake; for “Pray like us” it was a magnet with nails. For “Fight like us” it was a couple with surgical masks on who were kissing, which also addressed notions of ruthlessness, careerism, brittleness.

CS: So how did all of this relate to evangelism and crowds?

BK: While I was working on the script for that voice I had a lot of things floating in my head—like Bosnia, and all the daily horrors of “current events.” How the sanctity of the everyday— of shopping malls and renting a video and going for a ride—is busted apart by these conflagrations of hate and distrust and destruction. To me, the whole thing is a consideration of power.

CS: Even though the installation addressed fairly wide-ranging issues, it seemed mostly to speak to the fact that the fundamentalist, religious, far right in this country has taken over so much of public discourse.

BK: The focus was not primarily on the evangelical. It had to do in my mind with any kind of univocal discourse—if we can even call it a discourse—a rant, which says to people, “You do not agree with me, I am going to kill you. You do not agree with me, I want you disappeared.”

CS: But it is only the Christian right that exhorts crowds that way.

BK: Any football game has some of that in it, too. Sports were very much on my mind when I did this. If you listen to the announcer when the players come running out onto the field— there is this incredible voice, and the crowd just goes crazy. I believe sports function as one of our earliest devices for bonding in groups—certainly in a way that religion does not. Sports are one of the first us-versus-them imprints, aside from the obvious sexual and racial divisions. Most of the crowd noises on the sound track, all that cheering, were from sporting events—football, soccer games.

CS: What about the magnesium plates inset into the floor of the gallery?

BK: Those plaques were all questions, and I tried to use humor in them. When you first came in, the one you saw was a man shaking his finger—and to me that is the slogan for the whole show. It says, “How dare you not be me?” That’s the dance. That was a sort of mantra for the entire installation.

CS: Which comes back to crowds and what happens to people when they’re part of a crowd.

BK: I think so. The last Republican convention was an incredible spectacle. Chilling. Any sports event is probably the most eloquent distillation of that.

CS: Women didn’t seem to be very prominent in this installation.

BK: There were women in the crowd. There are a number of pictures of women in the larger images. One of them shows a woman with a hood over her head, and reads, “Your constant seeking for yourself and others, your campaign for a world without women,” in which the woman’s sexual identity is eclipsed.

CS: Is there a contemporary campaign for a world without women? What about the adulation of certain types of women, like fashion models?

BK: Certainly, the forces that oppose the idea of women as human beings, as minds and bodies with hopes, ambitions, and desires, and not just breeders who cook and clean, certainly those forces are on the march. Recently I read a very provocative book by David F. Noble, entitled, not coincidentally, A World Without Women. It is a wonderfully meticulous investigation into the origins and implications of the masculine culture of Western science, religion, and technology.

Ideas about power, gender, and exclusion were on the sound track in my brain when I was working on this installation. And this became distilled into an actual audio component of the exhibition.

CS: Are you working on any other large-scale installations?

BK: “Imperfect Utopia: A Park for the New World” is a project I have been collaborating on with the architectural firm of Smith-Miller & Hawkinson, the landscape architect Nicholas Quennel, and Guy Nordenson, an enginner with Öve Arup Inc. It consists of the development of land around the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. Like my other collaborations with Smith-Miller &c Hawkinson in Los Angeles and Seattle, this project contradicts the conventional notion of a “master plan,” breaking up the singular object of “building” or “artwork” or “site” into a multiplicity of procedures. Initially, we created a number of “zones” around the museum, created the kind of outdoor spectacle comprised of structures, words, excavations, still and moving images, and botany. It can be a space for relaxing, for movie-going, for reading, listening, or relaxing. We are trying to break down the categorical constraints of vocation (artist, architect, landscape architect, and engineer) and to think about the way museums make history and culture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

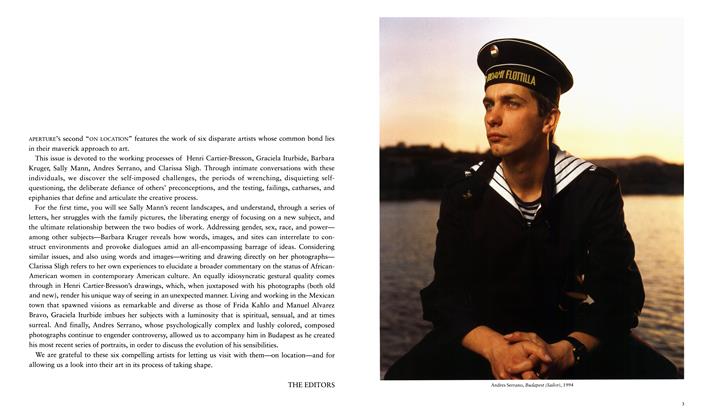

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Winter 1995 By John Berger -

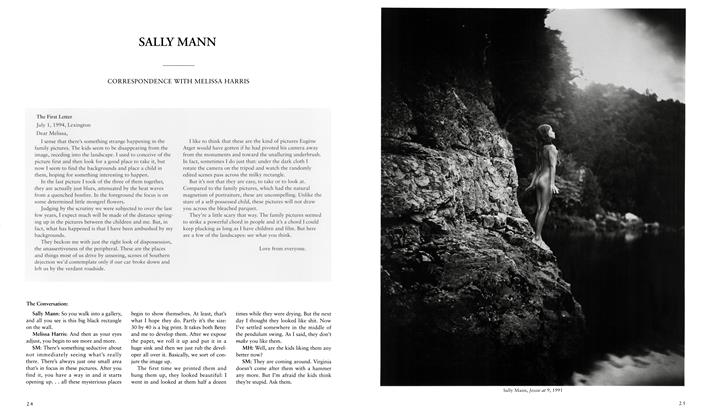

Sally Mann

Winter 1995 -

Pictures

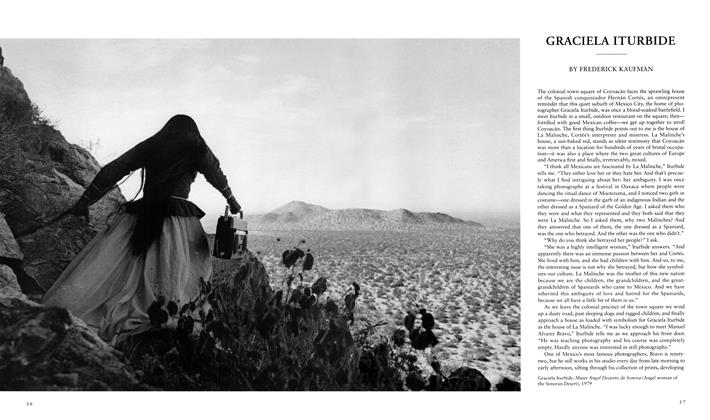

PicturesGraciela Iturbide

Winter 1995 By Frederick Kaufman -

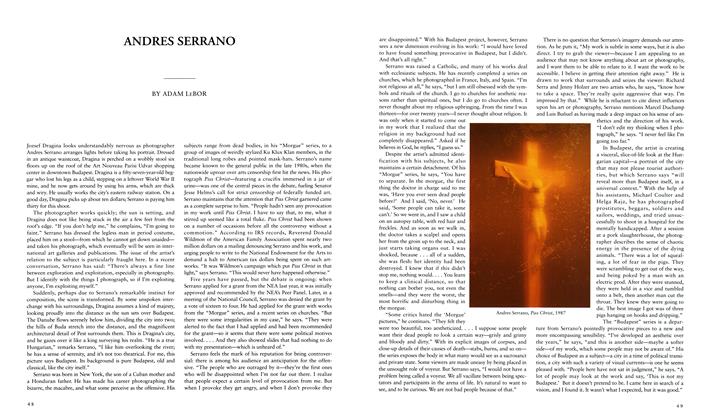

Andres Serrano

Winter 1995 By Adam Lebor -

Clarissa Sligh

Winter 1995 By Deborah Willis -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasDictatorship Of Virtue: Multiculturalism And The Battle For America’s Future, Richard Bernstein

Winter 1995 By Elizabeth Fox-Genovese