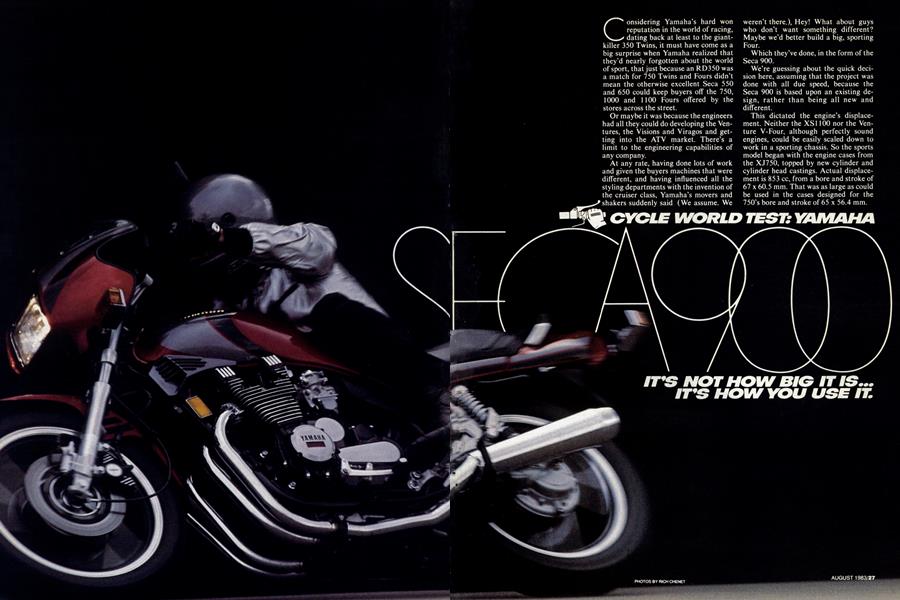

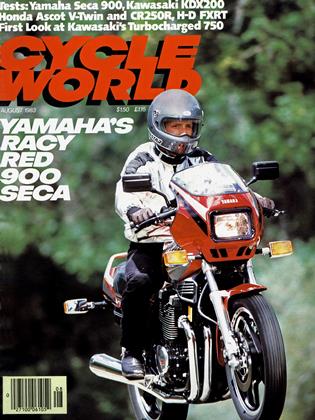

YAMAHA SECA900

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

IT'S NOT HOW BIG IT IS... IT'S HOW YOU USE IT.

Considering Yamaha’s hard won reputation in the world of racing, dating back at least to the giantkiller 350 Twins, it must have come as a big surprise when Yamaha realized that they’d nearly forgotten about the world of sport, that just because an RD350 was a match for 750 Twins and Fours didn’t mean the otherwise excellent Seca 550 and 650 could keep buyers off the 750, 1000 and 1100 Fours offered by the stores across the street.

Or maybe it was because the engineers had all they could do developing the Ventures, the Visions and Viragos and getting into the ATV market. There’s a limit to the engineering capabilities of any company.

At any rate, having done lots of work and given the buyers machines that were different, and having influenced all the styling departments with the invention of the cruiser class, Yamaha’s movers and shakers suddenly said (We assume. We weren’t there.), Hey! What about guys who don’t want something different? Maybe we’d better build a big, sporting Four.

Which they’ve done, in the form of the Seca 900.

We’re guessing about the quick decision here, assuming that the project was done with all due speed, because the Seca 900 is based upon an existing design, rather than being all new and different.

This dictated the engine’s displacement. Neither the XS1100 nor the Venture V-Four, although perfectly sound engines, could be easily scaled down to work in a sporting chassis. So the sports model began with the engine cases from the XJ750, topped by new cylinder and cylinder head castings. Actual displacement is 853 cc, from a bore and stroke of 67 x 60.5 mm. That was as large as could be used in the cases designed for the 750’s bore and stroke of 65 x 56.4 mm.

The crankshaft has plain bearings and is one mm narrower than the 750 crankshaft, measured outside flywheel to outside flywheel. But because the crankcase casting is from the 750 motor and the Seca 900 has a longer stroke, there wasn’t enough clearance for the connecting rod nuts at BDC. The solution was to reverse normal two-piece rod practice and mount the nuts up, with the rod bolts inserted through the rod caps.

The 900’s cylinder head is standard Yamaha XJ; two overhead camshafts, two valves per cylinder and the internal secondary passages Yamaha calls YICS and says improves mixture swirl and thus power and efficiency. Compression ratio is 9.6:1, the upper middle of current practice, and the cam lobes work directly on lash-adjustment shims recessed into the tappets. The shims are the same size (and interchangeable with) shims for the Seca 750/650/550 engines, making life easier for the home mechanic and the parts department.

The straight-cut primary drive gear is machined into the no. six flywheel and meshes with the clutch basket gear. (The clutch assembly itself is out of the Seca 650 Turbo). The two-shaft transmission has five gearsets and there’s a spring-loaded ramp-andcam damper on the countershaft, between the transmission gears and the bevel gearset used to transfer power to the driveshaft. That bevel gearset is from the Seca 750, but the driveshaft is 30mm longer than the 750’s driveshaft. The rear wheel hub incorporates rubber dampers behind the spiral bevel gearset, as seen before in the 650 Turbo and the Venture.

To reduce engine width, the 250w alternator is mounted on its own shaft behind the cylinders, a la 550/650/750, instead of the more conventional end-of-crankshaft mounting. The alternator shaft is driven off the crankshaft by a link-plate chain.

The transistorized ignition has an electronic advance. Carburetors are 35mm Mikuni CVs without accelerator pumps, with a new float bowl vent system to improve cold starting.

An expansion box is built into the chrome 4-into2 exhaust system, linking all four head pipes beneath the engine. The mufflers are upswept, and the inner wall of each dual-wall head pipe is stainless steel.

The oil pump is straight out of the Seca 750, and an eight-row aluminum oil cooler is standard.

The engine mounts solidly into the double-cradle, round-tubing steel frame. Rake is 27°, trail 4.5 in. Steering head bearings are tapered rollers, and both triple clamps are made of forged aluminum alloy. The forks have 37mm stanchion tubes, low-friction metal bushings and linked air fittings, allowing pressure to be adjusted through a single valve stem on the left fork leg. A forged aluminum brace bolts between the sliders, just above the fender. Fork compression damping is increased by an anti-dive fitting activated by brake system hydraulic pressure, but the amount of anti-dive effect and fork damping rates are not adjustable.

Like the steering stem, the swing arm pivot uses tapered roller bearings. The swing arm is made of rectangular cross-section steel, and the wheelbase is 58.3 in. Rear shocks are made by Yamaha under license from DeCarbon and are mounted with each shock body and its piggyback reservoir up, attached to the frame. The shocks have four-way adjustable rebound damping and five spring preload positions, and adjustments are made by using a shock wrench to turn rings at the bottom of each shock, beneath the spring.

Both wheels are aluminum alloy castings with a new spoke design, a 2.15 x 18 in. front and a 2.75 x 18 rear. Standard tires are a Bridgestone 100/90V18 L303 in the front and a 120/90V-18 G516 in the rear. All three brake discs measure 10.9-in. and are radially-vented with welded construction.

Each caliper has two opposing pistons and uses composite pads with sintered metal added.

The rubber-mounted footpegs are aluminum, as are the shift lever, brake pedal and peg mount plates. The handlebars are forged aluminum and are adjustable, moving forward and backward and up and down on serrated mounts. The choke is operated by a rotating collar with thumb tabs, built into the left control pod. Instruments include an electric tach and 150-mph eter, both with backlit, translucent needles. There’s also a constant-display LCD quartz clock, a fuel gauge and the usual collection of warning lights.

Styling is eye-catching, a small, handlebarmount fairing, a sleek tank curving down at the rear, integrated sidepanels and tailsection, all in bright, bright red set off with silver and black stripes. The engine is black with polished fins and covers, and the exhaust is chrome. There’s a silver, plastic scoop mounted under the front of the tank on each side, shaped to direct air onto the cylinder head. The sidepanels and scoops snap into rubber grommets, while the seat, which has a plastic base, is held by lever-operated latches secured by a key lock. The screw-in gas cap also locks, and one key operates the ignition/fork lock, seat and gas cap.

The Seca 900 weighs 518 lb. with half a tank of gas on Cycle World's certified scales. That makes it lighter than the current 1100s by an average of 44 lb. and about as heavy as a typical sporting 750. The Seca makes 85 bhp at 9000 rpm, the engineers say, and 59.3 lb.-ft. of torque at 7500 rpm. The latest 750s make about the same horsepower, but the Seca 900 has almost 20 percent more torque.

So the Seca’s dragstrip performance is no surprise. The Yamaha turned the quarter in 11.77 sec. with a terminal speed of 113.49 mph, and reached 130 mph in a half mile. The Yamaha needed 3.5 sec. to accelerate from 40 to 60 mph in top gear and 4.1 sec. to accelerate from 60 to 80 mph in top gear.

Those figures are off the pace of the 1100s, and right in the middle of the faster 750s. But the Seca 900 will accelerate about as hard as an 1100 from 40-60 mph in top gear, and harder than a typical 750 from 40 to 60 and from 60 to 80 mph in top gear.

What it all means is that the Seca, although less powerful than most 1100s, makes up for some of that disadvantage by being lighter. And while the Seca makes the same power as a good 750, with no weight advantage, its superior torque makes it as quick or quicker in top-gear acceleration even though it has taller gearing: at a true 60 mph the Seca is turning 4200 rpm, compared with 4700 for the Honda Interceptor, 4600 for the Suzuki GS750 and 4400 for the Kawasaki GPz750.

The Seca returned 53 mpg on the Cycle World mileage loop, giving it a cruising range of about 240 mi. before requiring reserve, at normal speeds. The Seca’s taller gearing made cruising more relaxed and helped the mileage, which is better than the mileage obtained from any of the recent fast 750s or 1100s.

What isn’t relaxed, is the suspension. The Seca turned in good braking distances but they came only after the forks were pressurized to 10 psi.

At 5.7 psi, the recommended setting, the forks bottomed under hard braking as the anti-dive didn’t seem to have any effect. Meanwhile the front end was firm with the factory setting and downright harsh pumped to work under braking. We took the pressure down to ambient and improved the ride while making the front end even more likely to hit bottom.

Things are no better in back. While rebound damping is adjustable, position No. 1 the lightest damping and position No. 4 the firmest, the entire range is too firm. Firm rebound damping is useful in controlling rear end rise and fall caused by shaft drive, but compromises suspension performance in other areas. The Seca started a slow weave as it reached 120-mph with a 145-lb. rider aboard and the rear damping set higher than position No. 1 (for minimum damping). With the same rider and the suspension turned down to position No. 1, the bike ran straight and true and steady at any speed. Heavier riders could run more damping without the problem, which was not affected by tucking in behind the fairing or removing the mirrors.

Single rear shocks are the trend in big street bikes these days, and such setups are receiving more engineering attention than dual-shock suspensions. But that alone cannot explain the Yamaha’s poor shock absorber performance, because the GS1100 Suzuki’s rear shocks are suitable for any type of riding, from touring to road racing. It’s more likely that the range of damping adjustments was limited to hold down production (and sales) costs.

With minimum shock preload, minimum shock damping and 10 psi fork pressure, the Seca works fairly well on twisty sections of pavement. As long as the rider is smooth and deliberate, without chopping the throttle mid-turn or at a corner entrance, because that’s when the Seca’s shaft drive intrudes. Turning on the power causes the rear end to rise, ánd shutting off causes it to sink, reducing available cornering clearance and affecting suspension loading as well. The rise and fall of the rear end is noticeable around town if the rider is clumsy with the throttle, but riders with a smooth hand won’t be aware of the shaft in urban riding.

The tips of the footpegs drag first when the Yamaha is ridden hard, and it takes serious riding to drag the pegs at all. Cornering clearance is excellent.

The seat has a nice shape but is too hard, and while the relationship between the footpegs and seat was fine, the reach to the handlebars and the angle of the grips pleased no one. In theory the handlebars are adjustable, but the adjustments are too coarse, the fairing gets in the way and no matter what we tried, we couldn’t get the bars angled or positioned the way we wanted. Because the bars are forged, rectangular aluminum, they can’t be replaced with tubular steel aftermarket bars. The idea of adjustable bars is good, but in practice these don’t live up to the theory.

Smooth is a word that applies to the Seca 900. It is the smoothest inline Four without rubber engine mounts, in terms of vibration reaching the rider—which is almost nil. The mirrors stay clear, the grips don’t buzz, the pegs don’t shake. It is a good example of how smooth a wellbalanced engine can be.

The 900 gets an award invented for this occasion, the trophy for Most Improved Clutch.

In general, recent high-performance bikes have had engines more than a match for their clutches. The Seca’s held up just fine. In family, recent Yamahas have been plagued by clutch drag, the result (we think) of an anti-rattle washer in the clutch basket. The XV920, the Seca 650 and the 650 Turbo were balky shifters as a result. But the Seca 900 shifts cleanly and the clutch slips when you want, grips when you want. Nothing in the spec sheet explains this, but the improvement is remarkable.

The fairing is more functional than it looks. No weather protection, obviously, nor can the rider get completely out of the windstream without lying flat on the tank. Instead, the fairing breaks the blast of air on the rider’s chest, and pays for itself on a long ride.

We also liked the clock. For the cost in instruments or current draw we liked knowing the time, rather than say, the gear we were in (we already knew) or being told we were in OD (which we don’t believe). The instruments are readable night or day, the quartz-halogen headlight is as bright as its description suggests, and the controls all work, although the choke control takes some getting used to simply because it’s different than anything we’ve seen before.

This is a good motorcycle. It isn’t as powerful as an 1100, but then it’s not as heavy. It isn’t quicker or faster than the latest 750s, but has a better powerband and turns fewer rpm at cruising speeds. The Seca’s engine is based on an existing, well-proven motor using conventional, easy-to-understand technology. It doesn’t have the latest, trickest features, but is easy to maintain largely for just that reason.

Perhaps the best way to consider the Seca is to avoid comparing it to either the 1100s or the 750s, instead accepting it for what it is and what it can do, for being a motorcycle. Look at what the Seca does and is. Think of where it can take its rider.

And if that’s where you want to go, what you want to do, then the Seca 900 deserves your attention.

YAMAHA

900 SECA

$3699

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

August 1983 -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

August 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

August 1983 -

Competition

CompetitionHonda's New Racers

August 1983 By Allan Girdler -

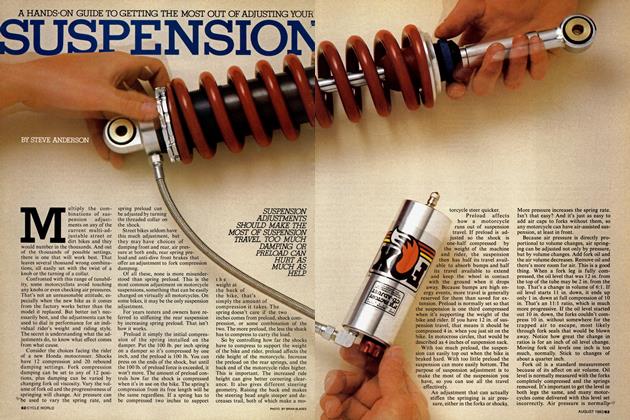

Technical

TechnicalA Hands-On Guide To Getting the Most Out of Adjusting Your Suspension

August 1983 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesParis-Dakar

August 1983 By Patrick Behar