Last week I discussed the various functional roles plants may serve in the landscape – with these practical considerations out of the way now, we can finally go about utilizing plants purely for their aesthetic appeal. However, we can’t just go plopping plants into our designs haphazardly. There is still a process – indeed this is inherent in the very definition of design. According to Wikipedia, design is defined as:

- the creation of a plan or convention for the construction of an object or a system

- a roadmap or a strategic approach for someone to achieve a unique expectation

Note the words ‘plan’ and ‘strategic approach’ – this suggests we must arrange our plants in a mindful, purposeful fashion. Nuff said? Okay I won’t belabour the point. Alrighty then let’s get going….

Um – where exactly do we go from here? There’s so much to choose from. Well let’s see if we can’t narrow down our choices by looking at what, where, when and why.

What Plants Should I Choose First?

Trees should always be your first consideration – they are the backbone of a well designed garden. Trees provide scale and structure, and since they take the longest to reach maturity, dedicating the largest portion of your plant budget to a few of these horticultural giants, means you’ll have good scale and structure from the get-go.

Once you’ve chosen your trees you can consider shrubs – if trees are the backbone of good garden design, shrubs are the rest of its skeletal structure. Perennials then, are the garden’s attire, and bulbs and annuals, the accessories.

The irony is, most of us have proceeded in exactly the opposite direction. Our first tentative foray into gardening often begins with brightly coloured annuals (I wince at the memory of marigolds and geraniums that were my first garden) or bulbs like tulips and daffodils. Soon we discover perennials, and sometime later (often much later) we start to think about shrubs and trees. I can tell you from experience that it is difficult to go backwards – save ripping it all up and starting over again, this backwards progression will always look like a retrofit.

So what kind of trees should you choose? It goes without saying that they should be of appropriate scale for your house, and of course you’ll choose what you personally find appealing, but there’s more yet to consider. Keep reading.

Where Should I Plant What?

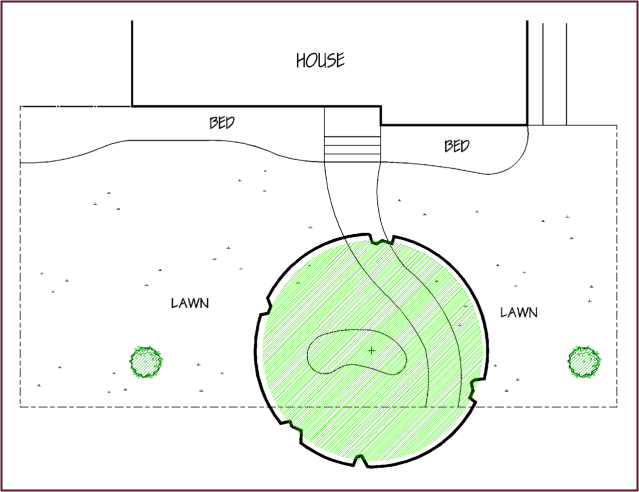

This really is the million dollar question isn’t it? To begin with you’ll need to take into account details like site exposure and available space, to ensure your plant choices will thrive where you place them. Next, consider plants which will present high visual impact and position them accordingly. For example a specimen tree or other dominant feature should be situated where it can take center stage. Use your design lines, and the shape of the spaces they create, to guide you – a swell in a garden bed or an area that is enclosed on three sides can provide a visual ‘frame’ for a feature tree or focal point.

Revisiting last week’s example – with the shade trees already in place, we can now add a specimen tree, say Sorbus decora. The outward curve of the back bed is just the kind of space that invites a special feature like this showy mountain ash, with its four-season appeal. We could also add some evergreens to anchor the corners – evergreens, because of their stiff needles and their density, provide visual weight.

Your design lines and resulting spaces can also help you organize and configure plant groupings. Looking again at the previous example, we see that the space beside the deck is somewhat wedge-shaped – note that the aspens are arranged to precisely fill that space. And the trio of spruces fit nicely into the triangular corner space. We can utilize the spaces between the various plantings in a similar fashion. Or we can emphasize a design line by bordering its entire length, or a portion thereof, with a single type of plant. And don’t forget to utilize Design Principles where applicable.

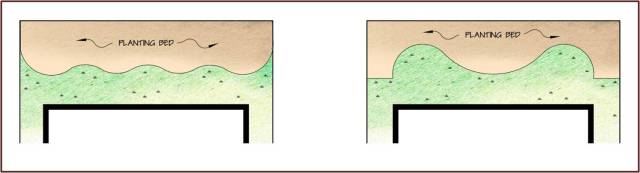

Juniperus sabina planted all along the edges of the curvilinear design lines, creates gentle movement and helps to emphasize the curves. The trio of Cornus sericea on either side also follows the curves, thereby reinforcing them.

Planting a single type of perennial along the entire span of a design line, as this homeowner has done, serves to reinforce the line. In this charming garden, low-growing Sedum edges the lovely arc of lawn space in the centre, as well as the straight lines abutting the sidewalks. Photo: Sue Gaviller

A generous swath of Thymus citriodorus ‘Doone Valley’ borders this softly curving bed.

Photo: Marg Gaviller

Straight lines are strong design lines. This impressive rectilinear design is well emphasized by the linear plantings of Salvia and Juniperus. Photo: Pat Gaviller

When (What Season) Should I Consider First?

This will depend on where you live and to some degree, your lifestyle. Where I live it can be winter for as much as 6 months of the year, so I usually start with winter interest – evergreens, woody plants with interesting form, and plants with colourful bark, berries or seedheads. For those who travel during part of the year, the season(s) to concentrate on would be when you are actually home to enjoy your garden or landscape. For example I have clients that spend winter in the South and summer at their cottage, so spring and fall are the seasons I considered first when choosing plant material. You’ll also want to make sure you choose plants that require very little maintenance during the growing season so you don’t come home from your cottage to a mess of deadheads and straggly foliage.

Planting for aesthetics in this client’s yard began with the two spaces circled on the left. Both are bordered on 3 sides with design lines – an ideal frame for a feature tree. The underplanting of spreading junipers creates a neutral, year-round prop for these four-season trees. See the ‘real life’ view below.

View from the side gate in late winter (top) and early summer (bottom). Photos: Sue Gaviller

Why Choose a Particular Plant?

Up to this point we’ve discussed plant choices mostly in general terms – size (i.e. trees first), visual impact (feature trees and anchors), cultural and maintenance requirements, and season of interest. Also worth considering are such things as tactile impression and fragrance – especially next to a patio, or in a garden designed for the visually impaired (the subject of another post). But the real reason most of us choose a particular plant is because we like how it looks – its form, its texture and/or its colour. Indeed these traits are the manner in which plants relate visually to each other, and to choose appropriately is to choose in the context of these relationships.

Last March I wrote about form, colour and texture in the winter garden – during the growing season however, these plant characteristics are that much more significant as there’s so much more plant material present. In the coming weeks I’ll be examining the visual impact of plant form, textural differences and colour relationships in order to help you arrange plants in the most effective and pleasing way.

Hope you can join me!

Til then, SueRelated articles

- Where Do We Go From Here? (notanothergardeningblog.com)

© Sue Gaviller and Not Another Gardening Blog 2012. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sue Gaviller and Not Another Gardening Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

In the examples to the left, the top image illustrates a house that is visually overwhelmed by the landscaping – the shrubs next to the house are as tall, or taller than the house, with some even obscuring windows. And the shade trees are huge in relation to the house – this scale is too large. The middle example is the exact opposite. The trees and shrubs look like toys in comparison to the house – the scale of this landscape is too small. The bottom example is what we’re after. The landscape elements are well suited to the size of the house, hence this represents appropriate scale.

In the examples to the left, the top image illustrates a house that is visually overwhelmed by the landscaping – the shrubs next to the house are as tall, or taller than the house, with some even obscuring windows. And the shade trees are huge in relation to the house – this scale is too large. The middle example is the exact opposite. The trees and shrubs look like toys in comparison to the house – the scale of this landscape is too small. The bottom example is what we’re after. The landscape elements are well suited to the size of the house, hence this represents appropriate scale.

The other thing that happens is illustrated on the left. In the top example, the diorama represents an older home with plantings typical of the time it was built – Cotoneaster hedge, Potentilla, and little Johnny’s ‘Arbour Day’ tree, a Colorado spruce (Picea pungens). Not particularly inspired I realize, but at least it’s in scale with the house. Fast forward a few decades and the scenario depicted in the bottom photo has likely ensued. Little Johnny is forty years old now and so is this landscape. I guess nobody took into account way back when, that living things don’t remain static. They grow … and grow and grow. So what was once in scale is no longer.

The other thing that happens is illustrated on the left. In the top example, the diorama represents an older home with plantings typical of the time it was built – Cotoneaster hedge, Potentilla, and little Johnny’s ‘Arbour Day’ tree, a Colorado spruce (Picea pungens). Not particularly inspired I realize, but at least it’s in scale with the house. Fast forward a few decades and the scenario depicted in the bottom photo has likely ensued. Little Johnny is forty years old now and so is this landscape. I guess nobody took into account way back when, that living things don’t remain static. They grow … and grow and grow. So what was once in scale is no longer.