Ballet in four acts and five scenes

Music by Adolphe Adam, Cesare Pugni, Grand Duke Pyotr Georgievich of Oldenburg & Léo Delibes

Libretto by Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Joseph Mazilier

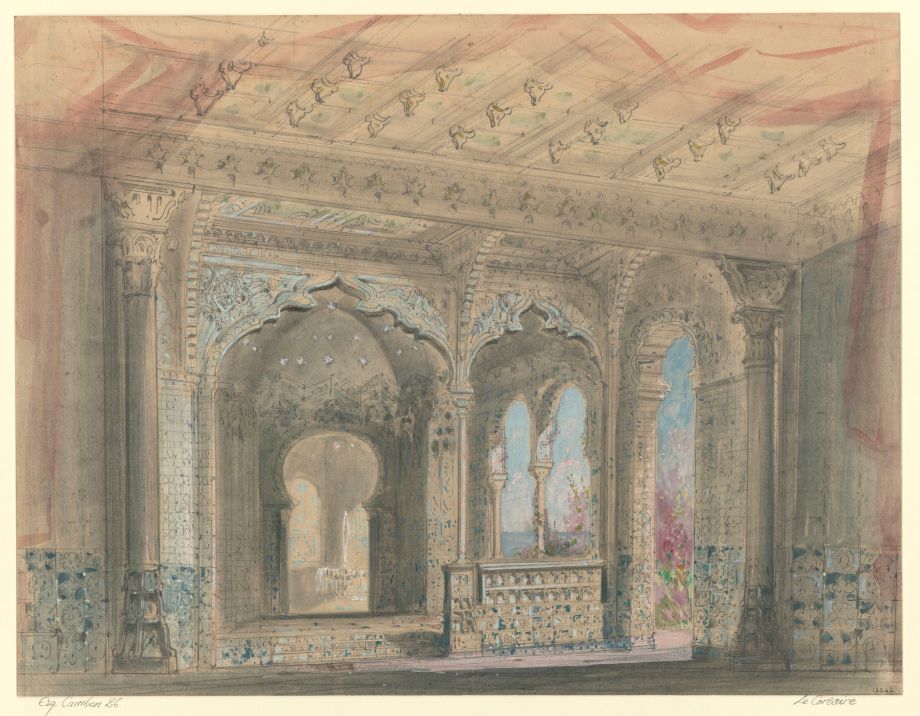

Décor by Andrei Roller and Heinrich Wagner

World Première

23rd January 1856

Théâtre Impérial de l’Opéra, Paris

Choreography by Joseph Mazilier

Original 1856 Cast

Medora

Carolina Rosati

Conrad

Domineco Segarelli

Gulnare

Claudina Cucchi

Birbanto

Alexandre Fuchs

Isaac Lanquedem

Francisque Garnier Berthier

The Seyd-Pasha

François Édouard Dauty

Saint Petersburg Première

24th January [O.S. 12th January] 1858

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

Choreography by Jules Perrot and Marius Petipa

Original 1858 Cast

Medora

Ekaterina Friedbürg

Conrad

Marius Petipa

The Three Odalisques

Nadezhda Amosova

Anastasia Amosova

Anna Prikhunova

Première of Petipa’s first revival

5th February [O.S. 24th January] 1863

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

Original 1863 Cast

Medora

Maria Surovshchikova-Petipa

Conrad

Marius Petipa

Gulnare

Anna Kosheva

Première of Petipa’s second revival

6th February [O.S. 25th January] 1868

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

Original 1868 Cast

Medora

Adèle Grantzow

Conrad

Marius Petipa

Première of Petipa’s third revival

12th December [O.S. 30th November] 1880

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

Original 1880 Cast

Medora

Eugenia Sokolova

Conrad

Lev Ivanov

Gulnare

Marie Petipa

Première of Petipa’s final revival

25th January [O.S. 13th January] 1899

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1899 Cast

Medora

Pierina Legnani

Conrad

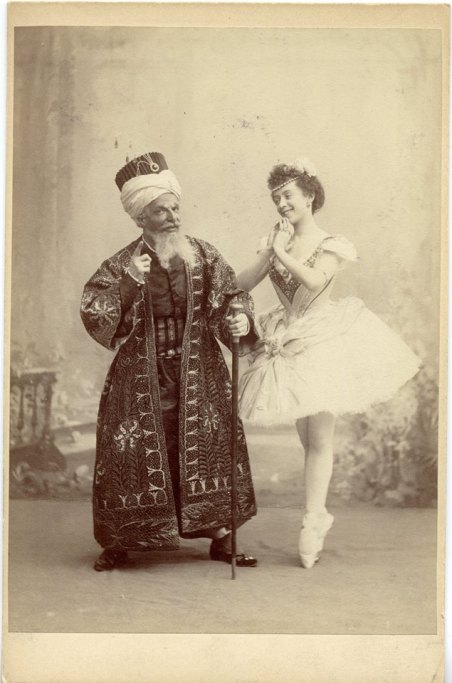

Pavel Gerdt

Gulnare

Olga Preobrazhenskaya

Birbanto

Iosif Kschessinsky

The Seyd-Pasha

Alfred Bekefi

History

The original production

Le Corsaire was one of the final creations by two of the 19th century ballet’s greatest figures – it was one of the last ballets created by Joseph Mazilier and the final ballet composed by Adolphe Adam before his death a few months after the première. The ballet was originally created for Carolina Rosati when she and her fellow Italian Amalia Ferraris arrived at the Paris Opéra in 1855 as the Opéra’s new Prima Ballerinas, taking the slot that had been left vacant by Fanny Cerrito after her retirement. It was for both Rosati and Ferraris that Mazilier created his last ballets – La Fonti and Le Corsaire for Rosati, Les Elfes for Ferraris and Marco Spada, in which both ballerinas appeared. The libretto was written by Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Mazilier and is loosely based on the poem The Corsair by Lord Byron, which tells of the corsair Conrad, who launches an attack on the Pasha Seyd.

The idea for Le Corsaire is rumoured to have come from a suggestion of Empress Eugénie, an avid balletomane. The rumours say that the Empress had suggested a ballet based on Byron’s Manfred and that Saint-Georges hoped for further assistance on a work based on one of Molière’s plays. The Empress even approached Charles Gounod on the matter, who was greatly astonished, but ultimately, nothing of Manfred came into fruition due to the Empress’s increasing preoccupation with matters of State. Nevertheless, it seems that her suggestion of a ballet based on a work by Byron steered the creators of Le Corsaire to his poem on which their new work would be based on. This gives Le Corsaire a unique place in history as the only ballet to which an Empress of the French Empire made a contribution.

While Rosati created the role of Medora, the most obvious candidate for the role of Conrad, the eponymous corsair, was Louis Merante after his performances in Gemma and La Fonti. However, the Opéra instead engaged the Italian mime Domineco Segarelli for, in accordance with the policies of the Paris Opéra at the time, Conrad was created as a purely mimed role and it would not be until many years later that the role included any dancing. The role of Gulnare was created by another Italian, Claudina Cucchi, a pupil of Carlo Blasis, who had débuted at the Opéra in 1855 in Lucien Petipa’s divertissements for the opera Les Vêpres siciliennes.

Libretto

The curtain opens on the bazaar market in the city of Andrianople (now the city of Edirne in modern-day Turkey) where the bazaar owner, Isaac Lanquedem is selling slave girls. A band of corsairs arrive, led by Conrad, who has come to meet the beautiful Medora, who is Lanquedem’s ward. Medora comes out onto her balcony and when she sees Conrad, she makes a selam of flowers and throws it down to him. Conrad is delighted as he is convinced that she reciprocates his love for her. The Pasha Seyd arrives in the square and the slave dealers crowd around him to offer him beautiful girls to sell, but none of them please him. However, he catches sight of Medora and is enraptured by her beauty. He insists on buying her, but Isaac refuses to sell his ward, explaining that she is not for sale and offers him other girls. But the Pasha is adamant on buying Medora and makes a very handsome offer for her, which Isaac cannot resist and he agrees to the sale. Delighted by his new purchase, the Pasha issues an order that Medora be delivered to his harem and threatens Isaac that there will be severe punishment if she is not brought to him. Medora is distraught by what Isaac has done, but Conrad calms her and promises that he will get her out this agreement, hatching a plan for the corsairs to “kidnap” her, to which Medora complies. Conrad calls the corsairs to start a merry dance with the slave girls, in which Medora also participates, much to the delight of everyone, but when Conrad gives the signal, the corsairs make off with the slave girls and Medora to their ship. Isaac chases after Medora, but he, too, is kidnapped and the corsairs make off for their hideout.

The second scene is set in the corsairs’ hideout, which is located on an island in the Aegean Sea. The corsairs bring in their new stolen treasures and captives. A series of dancing takes place, among which is the Grand Pas des Éventails, the original Grand Pas of the grotto scene. Set to Adam’s original music, the Grand Pas des Éventails is performed by Medora and sixteen coryphées with prop fans of different colours and at one point, the dancers come together and create a kaleidoscope effect reminiscent of a peacock’s magnificent plumage.

After the dancing, however, Medora is saddened by the sight of the captive maidens and begs Conrad to release them. He agrees, but this angers Birbanto, Conrad’s first mate, and the other corsairs, who argue they have a right to the women and a fight ensues. Conrad deflects a blow from Birbanto and forces him to his knees. Comforting the frightened Medora, Conrad takes her into his tent. Isaac attempts to escape amidst all the confusion, but he is caught by Birbanto and the others, who tease him and take all his money. However, they hatch a plot to retrieve Medora, to which Isaac complies in exchange for his freedom. Taking a flower, Birbanto coats it with a sleeping potion and tells Isaac to give it to Conrad, who will fall asleep if he smells it. Conrad and Medora emerge from the tent and Conrad arranges for dinner to be served. While everyone has their supper, Conrad and Medora declare their love for each other. As the corsairs disperse, Birbanto and his henchmen keep an eye on the lovers and their plan is put into action when Isaac appears with a slave girl, who he hands the drugged flower to and tells her to give it to Medora. Delighted by the flower, Medora takes it and gives it to Conrad, explaining it is a token of her love for him. However, when he smells it, the sleeping potion takes its effect and he passes out. Medora is horrified when she cannot wake him and suddenly, she finds herself surrounded by Birbanto and the others. In self-defence, Medora stabs Birbanto in the arm and attempts to flee, but the corsairs seize her and she faints, giving her kidnappers the advantage to snatch her away with Isaac following. Birbanto takes his dagger and attempts to kill the unconscious Conrad, but before he can stab him, Conrad wakes up and Birbanto, quickly hiding his dagger, tells him that Medora has been abducted. Conrad and the corsairs set off to rescue her.

The second act takes place in the palace of the Pasha, where many odalisques and harem girls live and among them is Gulnare. Zulma, the Sultana, demands respect from the girls, but they mock her. The Pasha enters and Gulnare proceeds to mock and tease him. Suddenly, the Pasha is informed that a slave dealer has arrived and he receives Isaac, who presents Medora, much to the Pasha’s delight. The Pasha offers Medora jewels and gifts, but she rejects them and seeing how unhappy she is, Gulnare approaches and comforts her. The Pasha orders for a series of dancing when a group of dervishes appear, but it is really Conrad and the corsairs in disguise. Conrad recognises his beloved among the harem girls and the dancing begins. Afterwards, Conrad gives the signals and the corsairs throw off their disguises. The corsairs ransack the palace and attempt to abduct the women. Birbanto seizes Gulnare, but Medora comes to her aid and then tells Conrad of Birbanto’s treachery. Furious, Conrad takes his pistol and prepares to shoot Birbanto, but Medora and Gulnare intercede and Birbanto escapes just as the Pasha’s guards run in. Conrad is seized, disarmed and sentenced to death.

The first scene of the third act begins with the Pasha making preparations for his wedding to Medora, but when he makes her an offer of marriage, she rejects him with content. However, Conrad is led to his execution in chains and Medora, heartbroken by the fate of her beloved, begs the Pasha to release him, but the Pasha makes a cruel deal – he will release Conrad, but only if Medora marries him of her own free will. Devastated by the offer, but determined to save her love, Medora agrees. The lovers are left alone and Medora explains to Conrad that she has consented to marry the Pasha in exchange for his life and freedom. Conrad rejects the deal and the lovers decide that they will die together. However, Gulnare approaches them with an idea that will set them both free – she will take Medora’s place as the Pasha’s bride as she will have her face covered with a veil so nobody will notice the switch. Overcome with relief and gratitude, Conrad and Medora agree to the plan and thank Gulnare profusely. The hour of the wedding comes and the bride enters wearing a veil over her head. The Pasha puts a ring on her finger and they are married. Afterwards, the Pasha gives orders for Conrad to be released. When he is alone with Medora, she attempts to entice him and persuades him to hand her Conrad’s pistol and sword. The hour of Medora’s delivery arrives and Conrad enters; the two threaten the Pasha with their weapons and flee to Conrad’s ship. The horrified Pasha calls in the guards and his entourage, informing that his wife has been abducted, but Gulnare steps forward and reveals that she is wearing the ring that the Pasha gave to his bride, announcing that she is the Pasha’s lawful wife, not Medora. The Pasha and everyone else are left in a state of shock.

In the final scene, the corsairs’ ship is sailing away to new adventures. Birbanto is in chains for his treachery, but Medora, pitying him, asks Conrad to forgive him and he agrees. He orders for Birbanto to be unchained and calls for wine to be served as all onboard celebrate their liberty, with Conrad and Medora basking in the happiness of their reunion. But then, there is a swift change in the weather and a terrible storm breaks out. Birbanto takes advantage of the confusion and challenges Conrad, but is defeated and stabbed. The ship runs aground on a rock and is destroyed; the corsairs are thrown into the raging sea. As the storm calms and the moon appears in the night sky, two figures are seen climbing onto the rocks. It is Conrad and Medora, who have miraculously not drowned; they embrace one another and give thanks to God for their survival.

World première

Le Corsaire premièred at the Paris Opéra on the 23rd January 1856 to great success. Rosati’s performance as Medora was hugely praised, arousing much enthusiasm in the audience and critics. The critic Benoît Jouvin named her “the first ballerina in the world,” and went onto write:

“The latest comer among the danseuses of “style” – Carlotta Grisi, [Fanny] Cerriot, Fuoco – La Rosati possesses more stamina than the first, a more distinguished grace than the second, and quite as much intrepidity as the third, ad in addition has an originality more marked than that of all three put together.” – quoted in The Ballet of the Second Empire by Ivor Guest, p. 99-100

Jules Janin, who had been one of her biggest critics at her Opéra début, went further in his review:

“Carlotta, who was so enchanting, had not greater charm; Fanny Elssler was never more enticing. [Rosati] is light-footed in the manner of Mlle Taglioni herself.” – quoted in The Ballet of the Second Empire by Ivor Guest, p. 101

Segarelli proved to be more than suitable for the role of Conrad, although, by French standards, his Italian style of mime was considered exaggerated by the Parisian audience. It was not just the performances of the lead dancers that contributed to the ballet’s success, but the production itself. The ballet was first and foremost a ballet d’action made up mostly of mime with quite a smaller amount of dancing, but there were no dull moments. However, Mazilier’s choreography was considered to be lacking in originality. The most successful dance number was the Pas des Éventails of Act 1, scene 2, but it was not the choreographic steps that made it remarkable, but rather the blending of the colours of the fans. Other dance numbers included a pas seul for Rosati in Act 2 and she also danced on the deck of the ship in Act 3. Act 1, scene 1 contained a divertissement for five slaves from different countries – Moldavia, Italy, France, England (according to the libretto, but the danseuse Victorine Legrain wore a Scottish costume) and Spain – and each danced a national pas.

The highlight of the production was not a dance number, but the shipwreck scene of the final act, which proved to be the key to the ballet’s success. One critic wrote, “Crosnier has saved the Opéra by a shipwreck,” but the credit was actually owed to the chief machinist Sacré. Jouvin wrote of the shipwreck:

“The sky, the waves, the horizon pass, by degrees that are menon. A splendid sunset in the Black Sea – a ship that seems to fall asleep to the murmur of the waves, like a child soothed by its nurse’s lullaby – the dancing and the orgy on board. Then, suddenly, a black speck on the horizon – the whistling of the rising wind – darkness falling – the sky here and there fringed with a sinister red glow – heavy peals of thunder in the distance. Finally, the storm – nightfall – the furious sea – the silhouette of the vessel, rocking with increasing force and then foundering with a dreadful noise. All these incidents of a shipwreck were rendered with a complete illusion by the scene-painter and the machinist. The Opéra stage seemed to have taken on suddenly the vast proportions of the open sea. It was better than the mirage produced by the Diorama; it was reality in all its grandiose horror.” – quoted in The Ballet of the Second Empire by Ivor Guest, p. 101

The ballet would probably have not been as successful as it was without Adam’s score, which is where the beauty of the ballet is to be found. It was his last work for, months after the première, on the 2nd May 1856, Adam passed away peacefully in his sleep. Le Corsaire was the swansong of the man who was probably the Romantic Ballet’s greatest composer.

Le Corsaire in Russia

Le Corsaire was first staged in Russia for the Imperial Ballet by Jules Perrot on the 24th January [O.S. 12th January] 1858 with the Prima Ballerina, Ekaterina Friedbürg as Medora and Petipa as Conrad. For this production, Petipa assisted Perrot in rehearsals and even revised several of the ballet’s key dances; the most noted being the Grand Pas des Éventails and the Scene de séduction of Act 1, scene 2. Petipa also introduced two new dance numbers, which have since become two of the ballet’s most famous pieces. The first was a pas de deux for the first scene entitled the Pas d’esclave, which was performed by a young Marfa Muravieva, a rising star, who had recently graduated from the Theatre School, and was set to music composed by the Grand Duke Pyotr Georgievich of Oldenburg. In many productions, the Pas d’esclave is performed by Gulnare and Isaac Lanquedem, but in the original context, it is performed by two anonymous slaves who have no other part in the ballet’s action.

The second new number Petipa introduced was a pas de trois for the second act entitled the Pas de trois des odalisques. In the original 1856 production, this number was originally a waltz performed by a group of harem girls to entertain the Pasha’s Sultana. In the 1858 revival, Petipa revised and expanded this piece into a classical pas, consisting of an entrée, three variations and a coda. The entrée is set to Adam’s original music, while the first and second variations and the coda are set to new pieces composed by Cesare Pugni. The third variation was transferred from another part of Adam’s original score. Petipa’s revised and expanded Pas de trois des odalisques was first performed by the ballerina Anna Prikhunova and the famous twins Nadezhda and Anastasia Amosova.

Petipa’s revivals

Throughout his sixty-year long career, Petipa staged four revivals of Le Corsaire; his first revival was staged especially for his wife Maria Surovshchikova-Petipa, with Petipa himself as Conrad and the ballerina Anna Kosheva as Gulnare. The production was premièred on the 5th February [O.S. 24th January] 1863 with a supplemented and revised score by Cesare Pugni. The most famous of Petipa and Pugni’s new additions for this revival was a new travesti variation for Mme. Petipa entitled Le Petit Corsaire, in which Medora, dressed as a corsair, dances for Conrad and the other corsairs with a prop megaphone. During the dance, she mimes the phrase, “I have no moustache, but nonetheless, my heart is as strong as a man’s!” In the original production, the variation ended with Mme. Surovshchikova-Petipa calling out in French, “Au bord!” the nautical command given by corsairs before plundering another vessel.

In her memoirs Theatre Street, Tamara Karsavina gives a detailed account of Le Petit Corsaire:

The romantic quality of Medora’s part is set off by a little episode of spontaneous gaiety; Conrad is sombre, and to distract his mind Medora, in boy’s apparel, dances for him. She seems to say by her frolicsome dance: ‘Alas, I have no moustache, but my heart is as valiant as a man’s own.’ A never-failing effect comes at the end; Medora, through a speaking, cries words of nautical command.

The short, pleated skirt, bolero and fez of the costume that Maria Sergeyevna Petipa herself wore had been replaced by the ample trousers and turban of a Turkish boy. (…) The costume led me astray. Precepts of coy grace were forgotten; the trousers wanted me to leap and romp. From there the logical conclusion was not to apologize for the want of moustache, but to pull fiercely at an imaginary one. Encores told me of the success of my spontaneous inspiration. [Pavel] Gerdt, my darling Conrad, in the passionate embrace of the concluding scene, in a ventriloquist whisper, conveyed: ‘Well done, goddaughter.’

Le Petit Corsaire became one of the most celebrated passages of Le Corsaire in Imperial Russia; its first performance delighting the audience, especially Mme. Petipa’s fan base. It later became one of the first pieces in the art of ballet ever to be documented to film. It was Alexander Shiryaev who was responsible for filming his wife Natalia Matveyeva performing the dance in the early 20th century.

On the 6th February [O.S. 25th January] 1868, Petipa staged his second revival of Le Corsaire especially for the German ballerina, Adèle Grantzow. As with his first revival, Petipa called upon Pugni to compose new dances, among which was a new pas de six for Grantzow in the grotto scene, which replaced the Grand Pas des Éventails, but what stands out about Petipa’s second revival is that this was the staging that saw the introduction of the ballet’s most famous number Le Jardin Animé. A year earlier, in 1867, Joseph Mazilier came out of retirement to mount a revival of Le Corsaire in honour of the 1867 Exposition Universelle given that year in Paris. Before she was invited to Russia, Grantzow danced Medora in Mazilier’s revival and for her performance, Adolphe Adam’s former pupil, Léo Delibes composed new music, among which was a new pas des fleurs. Delibes’ new music additions included a waltz that he originally composed for his ballet La Source, which premièred at the Paris Opéra in 1866 with choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon. It is known as the Naïla waltz, but in the end, it was never used in La Source and he revived and inserted it into his new pas des fleurs as the opening waltz. After Grantzow’s departure from Paris in 1868, Le Corsaire’s time in the Paris Opéra’s repertoire expired and it has not been performed by the company ever since. Delibes’s new Pas des fleurs was retained by Petipa for his second and subsequent revivals of Le Corsaire. He greatly revised and expanded this pas into a new and elaborated version called Le Jardin Animé, complete with garlands and a manicured lawn à la the gardens of Versailles. An interesting passage of Le Jardin Animé that has been changed in modern productions is the opening sequence Medora performs at the start of the adagio. In most stagings today, Medora holds a pose en attitude, but in Petipa’s staging, she performs four développés to the front with each one getting higher and higher, as if to represent a blooming flower.

By the 1870s, the role of Conrad had ceased to be a purely mimed role and there was a famous performance in 1887 when Enrico Cecchetti danced up a storm in the role, alongside his fellow Italian Emma Bessone as Medora. For this performance, Petipa and Riccardo Drigo composed and added a new pas de deux for Cecchetti and Bessone in the grotto scene, again replacing the scene’s grand pas. Petipa’s third revival of Le Corsaire was staged especially for the Russian Prima Ballerina Eugenia Sokolova on the 12th December [O.S. 30th November] 1880 and finally, his fourth and most important revival was staged on the 25th January [O.S. 13th January] 1899. Petipa staged his final revival for Pierina Legnani, who danced Medora alongside Pavel Gerdt as Conrad and Olga Preobrazhenskaya as Gulnare.

Le Corsaire was notated in the Stepanov notation method and is part of the Sergeyev Collection. Notation for the ballet first began in 1894 with the famous Le Jardin Animé scene becoming the first passage from the full-length ballet ever to be notated. The notation of the full-length ballet was completed between 1904 and 1906.

Le Corsaire in the 20th Century

After Petipa’s retirement in 1904 and the 1917 Revolution, Le Corsaire went onto become one of the most heavily revised and reworked ballets in the 20th century. In 1912, a new revival was staged in Moscow by Alexander Gorsky and remained in the repertoire until 1927. Petipa’s 1899 production remained in the Saint Petersburg repertoire until 1928, though in 1915, it underwent a new revival by Samuil Andrianov, who is noted for being the teacher of the young George Balanchine. For this revival, Andrianov discarded the Grand Pas des Éventails in the grotto scene and replaced it with a new pas d’action that was performed by Andrianov as Conrad, Tamara Karsavina as Medora and Anatoli Obukhov, who served as an additional cavalier. In 1931, Agrippina Vaganova transformed Andrianov’s pas d’action into a classical pas de deux for the graduation performance of her star pupil Natalia Dudinskaya, who was partnered by Konstantin Sergeyev. This is the pas de deux that became the famous so-called Le Corsaire Pas de deux. Contrary to popular belief, this pas de deux was not created by Petipa and does not contain any of Adam’s music from his full-length score. After Petipa’s retirement, it became more common at the Mariinsky to set a novelty piece to a pastiche of music taken from various sources chosen by dancers and/or the choreographers. The so-called Le Corsaire Pas de deux is one such piece, as are many famous pas de deux created thereafter. The music used for this pas de deux is a pastiche of pieces by Riccardo Drigo, Yuri Gerber Baron Boris Fitinhoff-Schell and Prince Ivan Troubetskoy:

- Adagio – an orchestration of Drigo’s nocturne for piano called Dream of Spring, a piece that he never intended for choreography.

- Male variation – a variation by Yuri Gerber from his 1870 ballet Trilby.

- Female variation – a polka-rhythm variation by Fitinhoff-Schell from Lev Ivanov and Enrico Cecchetti’s 1893 ballet Cinderella.

- Coda – a piece by Prince Troubetskoy from his 1883 ballet Pygmalion, or The Statue of Cyprus.

After the rise of the new Soviet regime, Vagaonva supervised the first Soviet production of Le Corsaire for the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet, which premièred on the 15th May 1931 and starred Mikhail Dudko as Conrad. In 1936, another revival of Le Corsaire was staged for the Kirov/Mariinsky and it was this production that inserted Vaganova’s revision of the so-called Le Corsaire Pas de deux into the full-length ballet. It was performed by Dudinskaya as Medora, Mikhail Mikhailov as Conrad and Vakhtang Chabukiani as the slave.

In 1955, a new production was staged by Pyotr Gusev for the Maly/Mikhailovsky Ballet, which used a modified version of the original libretto written by Gusev and Soviet dance historian Yuri Slominsky. It was this production that introduced the slave Ali, a new character evolved from the unnamed slave that performed in the so-called Le Corsaire Pas de deux. To fit his new libretto, Gusev collaborated with the conductor Eugene Kornblit to not just rearrange the score, but to introduce a new one. While the traditional pieces were retained, the majority of Adam’s original score was discarded and replaced with a pastiche of numbers taken and fashioned from his 1840 ballet L’Écumeur de mer (The Pirate) and his 1852 opera Si j’étais roi. The new music was even used to create new leitmotifs for the main characters. Some the most notable changes Gusev and Slonimsky made to the libretto include: the shipwreck takes place in a newly-created prologue instead of the ballet’s finale; Medora is a slave girl rather than Isaac Lanquedem’s ward; Medora and Gulnare are friends at the beginning of the ballet and Conrad and Medora meet for the first time and fall in love in the first act. Conrad’s capture and death sentence, Medora’s forced wedding to the Pasha and Gulnare switching places with her as the Pasha’s bride are omitted and the ballet ends on a new epilogue that sees Conrad, Medora, Gulnare and Ali sailing away together to new adventures. Gusev’s production premièred on the 31st May 1955 and became the most popular production of Le Corsaire in Soviet Russia. It was later staged for the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet in 1977 by Oleg Vinogradov and is still performed by the company today.

In 1973, Konstantin Sergeyev staged his own production of Le Corsaire for the Kirov/Mariinsky, but it was pulled from the repertoire after only nine performances, possibly because Sergeyev had fallen out of favour with the Soviet authorities after the defections of Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov. In 1992, Sergeyev was invited to stage his production in Moscow for the Bolshoi Ballet at the request of Yuri Grigorovich. It premièred on the 11th March 1992, just weeks before Sergeyev’s death, but it was dropped from the Bolshoi repertoire after only seven performances. Grigorovich would later stage his own production for the Bolshoi Ballet in 1994, but it was removed after he left the company in 1995.

Like many of the ballets staged by Petipa in Saint Petersburg, Le Corsaire was not included in the western repertoire for the majority of the 20th century. Only the so-called Le Corsaire Pas de deux was performed by western companies after it was staged by Rudolf Nureyev for himself and Dame Margot Fonteyn at the Royal Opera House in 1962. It would be thirty-five years later that the full-length ballet would be reintroduced to the west when Sergeyev’s revival was eventually given a home in the USA after Natalia Dudinskaya suggested to her Canadian student Anna-Marie Holmes that she should stage it for the Boston Ballet. Holmes was assisted in the staging by Dudinskaya, Tatiana Terekhova, Sergei Berezhnoi, Tatiana Legat and Vadim Disnitsky and the new production had its world première on the 27th March 1997 at the Wang Center in Boston. A year later, the production was bought by American Ballet Theatre and went through more choreographic and musical revisions. The new revival premièred on the 19th June 1998 at the Met Opera House, with Nina Ananiashvili as Medora and the production has since remained a prominent member of the ABT repertoire.

In 2013, Holmes staged a new production for the English National Ballet, which is based on her American productions and includes new décor and costumes and a re-working of the score with new orchestrations. Holmes’s production of Le Corsaire for ENB is the first full-length production to be danced by a British ballet company and they have performed it across the UK in their regional tours. In 2006, Ivan Liska, the then-director of the Bayerisches Staatsballet, staged a new production of Le Corsaire in Munich, which included twenty-five notated passages from the Sergeyev Collection, reconstructed by Doug Fullington, including the Pas d’esclave, the Pas de trois des odalisques and Le Jardin Animé. In 2007, Le Corsaire made a comeback to the Bolshoi Theatre when a new lavish production was staged by Yuri Burlaka and Alexei Ratmansky. This production restored the libretto, music score and décor and costumes from Petipa’s 1899 revival and the Le Petite Corsaire variation, which had not be seen in Russia for many decades, but the production is not a reconstruction of the notation scores. It also includes some new choreographic additions, most notably a new pas des éventails in the third act, which is set to music pieces from Riccardo Drigo’s score for The Enchanted Forest.

Related pages

Photo gallery

Sources

- Ivor Guest (2014) The Ballet of the Second Empire. Binsted, Hampshire, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Ivor Guest (2008) The Romantic Ballet in Paris. Alton, Hampshire, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Ivor Guest, CD Liner notes. Adolphe Adam. Le Corsaire. Richard Bonynge cond. English Chamber Orchestra. Decca 430 286-2.

- Doug Fullington, Petipa’s Le Jardin Animé Restored. The Dancing Times: September 2004. Vol. 94, No. 1129.

- American Ballet Theatre: Theatre program for Le Corsaire. Playbill 24-26,31. 2005

- Bayerisches Staatsballett (Bavarian State Ballet): Theatre program for Le Corsaire, 2007

- Bolshoi Theatre: Theatre program for Le Corsaire, 2007

- Mariinsky Ballet: Theatre program for Le Corsaire, 2004

Photos and images: © Dansmuseet, Stockholm © Большой театр России © Victoria and Albert Museum, London © Государственный академический Мариинский театр © CNCS/Pascal François © Bibliothèque nationale de France © Musée l’Opéra © Colette Masson/Roger-Viollet © АРБ имени А. Я. Вагановой © Михаил Логвинов © Михайловский театр, фотограф Стас Левшин. Партнёры проекта: СПбГБУК «Санкт-Петербургская государственная Театральная библиотека». ФГБОУВО «Академия русского балета имени А. Я. Вагановой» СПбГБУК «Михайловский театр». Михаил Логвинов, фотограф. Martine Kahane.