Kiruna: How to move a town two miles east

- Published

This spring work will begin to move Sweden's northernmost town two miles to the east. Over the next 20 years, 20,000 people will move into new homes, built around a new town centre, as a mine gradually swallows the old community. It's a vast and hugely complicated undertaking.

"When people hear that we're designing, creating and building a whole new city from scratch they think we're doing a utopian experiment," says architect Mikael Stenqvist.

But there's too much at stake to think of it as an experiment, he says.

"If this project goes wrong, the survival of Kiruna, its inhabitants and its economy is at stake. That gives us great concern - unlike any other project we work on."

More than 3,000 apartment blocks and houses, several hotels and 2.2m sq ft (0.2m sq m) of office, school and hospital space will be emptied over the next two decades - while alternatives are built on the new site.

The old church voted Sweden's most beautiful building in 2001 will be taken apart, piece by piece, and rebuilt.

"We want to have as much of the existing character from the old city as possible, but costs and market mechanics mean we can't move everything," says Stenqvist.

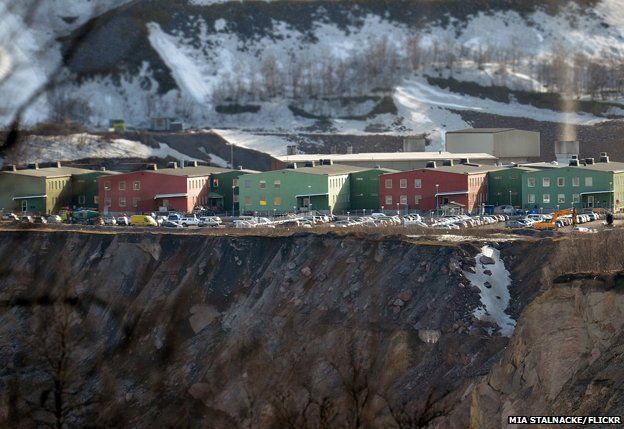

The move has been dictated by the local iron mine - one of the most valuable iron ore deposits in the whole of Sweden, and Kiruna's largest employer.

The story began in 2004, when the state-owned mining company, Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara AB (LKAB), sent a letter to the local government explaining that it needed to dig deeper into a hill just outside the town, which could cause the ground beneath thousands of apartments and public buildings to crack or give way.

A decade later, sure enough, huge fissures are appearing across the city, creeping towards the centre.

"Everyone that lives in Kiruna has known that the city will eventually be relocated - everyone can see the mines eating up the city," says Viktoria Walldin, one of the social anthropologists hired to work on the relocation. "The question has always been when."

Kiruna's inhabitants have been living in a "subliminal state" for almost 15 years, Walldin says, unable to make major life decisions such as buying a house, redecorating, having a child or opening a business.

"Now it's finally time for a lot of people who have mentally been living in a state of stasis for years to finally release themselves and think: 'It's finally happening, I'm going to be able to make investments and plans for the rest of my life.'

"They want to see a school, a hospital - until then they're sceptical... they've been being told the relocation is about to happen forever."

For them, the groundbreaking at the new town centre next month will be a momentous event.

The number of people involved in a project of this scale exceeds the thousands and includes city planners, architects, landscape designers, biologists, urban designers, civil engineers, demolition and construction experts and builders, as well as social anthropologists like Walldin.

The Stockholm-based architects White Arkitekter AB, which won the contract to design the new Kiruna, envisages a denser city centre with a greater focus on sustainability, pedestrians and public transport than automobiles.

The city's location 145km (90 miles) north of the Arctic Circle means that it's in perpetual daylight from May to August and perpetual darkness from December to late January. Temperatures remain below -15C (5F) for much of the year, with snowfall all year round.

"Narrow streets in the designs will break the wind and cold better, but then the city will be harder to navigate," says Stenqvist. "We have specialists looking at how to construct houses and buildings in this climate while still having a low energy impact."

A new town hall, planned for completion in 2016, will be accompanied by a public square and a train station, on a plot that currently houses a half-occupied industrial estate.

One of Walldin's jobs is to talk to people to find out what they want from the new town, and to convey that to the architects.

"There is a tension between nature and culture in Kiruna," says Walldin. "The city has never had culture in its existence - places to meet, eat and interact. We want to make sure the department of culture, of social welfare, of leisure are all consulted to provide movie theatres, swimming halls, football arenas in the new city."

The new town could also solve some of Kiruna's problems - including a severe gender imbalance.

"This is a very male-dominated city as most young women move away," says Walldin. "The new city desperately needs to be able to attract women to live here."

It's also hoped the new, improved city will encourage more tourists to the area, helping local business. The world-famous Ice Hotel in nearby Jukkasjarvi attracts more than 100,000 people to the area every year, but tourists rarely bother to make the 15-minute journey to Kiruna.

From an anthropological point of view, there is one major concern - the "people in Kiruna who are stuck in old memories", as Walldin puts it.

"You have to find a way to both respect the memories and take care of the people who have been living in limbo in this city for over a decade," she says. "People who had their first kiss on that bench or their first child in that hospital will now see these things totally disappear."

Before anyone can move, LKAB has to buy their existing property, so that they can buy a new one in the new town. But the sums are nightmarish.

"The general idea is for LKAB to purchase people's homes from them at market value plus 25%, and then sell them a property in the new city," says Stenqvist. "But how do you work out what the market value is for a house in a city that doesn't even exist?"

White Arkitekter have monitored all the housing lettings in nearby cities over a period of years, and then "tagged" the Kiruna houses with each asset they possess, such as space, gardens, and proximity to the city centre.

"We're even putting a monetary value on bus stops - how close a house is to one could be very important in a new city designed around its public transport system," Stenqvist says.

Similarly, shop and business owners who believe they have a "good spot" in the current city have voiced concerns over their proposed, but yet unknown, location in the new one.

"It's a new situation and no-one really knows how to handle it," says Yvel Sievertsson, urban transformation officer at LKAB. "We have hundreds of people working on the issue alone, including researchers at the University of Stockholm. The goal is to have the new city centre ready before we start to move everyone over, and then to move everyone at once in one or two stages, to impact people's businesses as little as possible."

"We have been around the world looking at how other countries like Germany and parts of Africa have handled similar projects, but they are just moving small villages and houses, not huge city centres," says Sievertsson. "We're using all the expertise we can to help us, but it's a completely unknown situation."

Paradoxically, new housing will have to be built in the existing town, before work gets going on the new one, as Kiruna needs up to 800 more living spaces in order to house the workers coming to build the new city. "It's a Catch 22 situation," says Peter Johansson, construction manager at NCC, the company leading the building of the new town.

The sheer scale of the plans mean anxiety is rising over whether the project will be completed on schedule.

"The municipality and LKAB think we can build this entire city in four or five years, but it's impossible," says Johansson. "It's more of a vision than a truth that the building will begin this spring. We should have started building in 2009 or 2010.

"We have about 250 people working on the sites but we need more than 1,000. We would need workers from all over Scandinavia to make this project possible."

LKAB has already spent 4bn kronor (£366m, or $612m) on the project to date and has earmarked 7.5bn kronor for the remaining transformation, though it says it's impossible to estimate the total cost of the project.

A sense of waiting for something to happen is tangible, but the town's residents largely support the relocation. The local economy is almost entirely dependent on the success of the mine.

"LKAB manages the mine, gives people work, and some of Kiruna's inhabitants have become very wealthy from it," says Walldin. "The mine is the reason they are all there."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine on Twitter and on Facebook