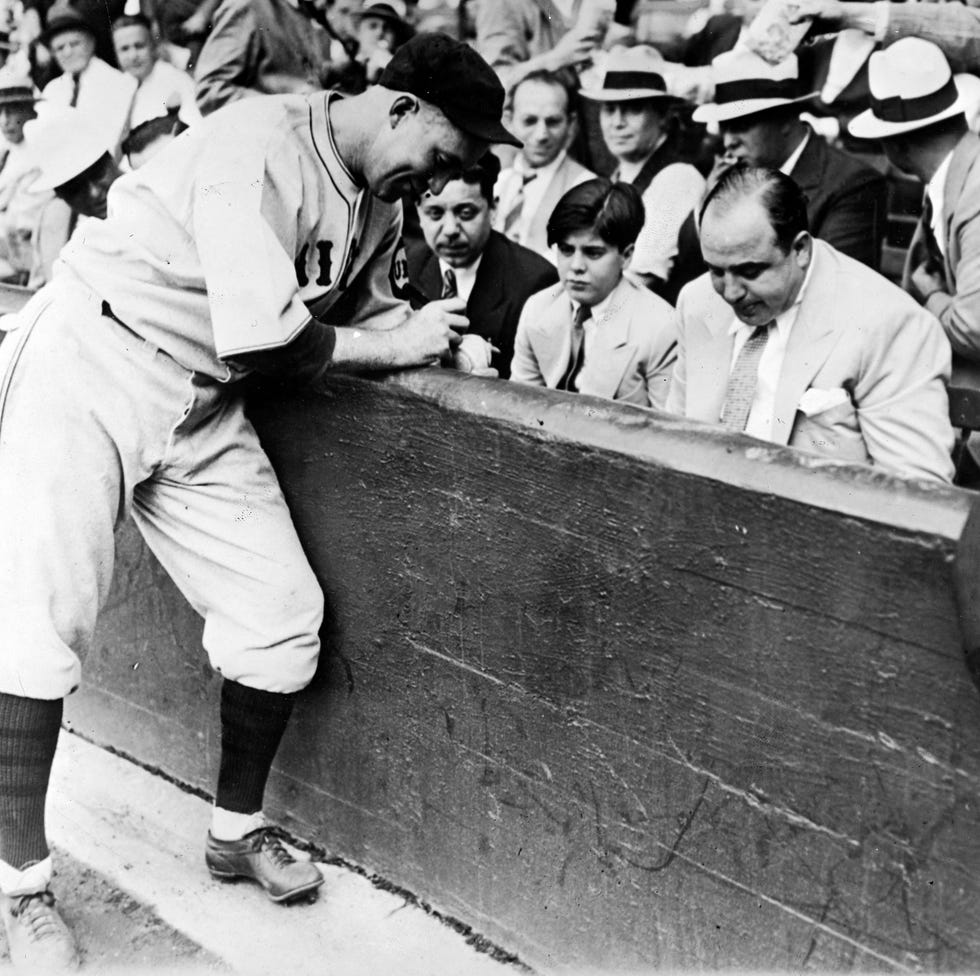

At the peak of his career as a crime lord, Al Capone helmed an organization that took in the equivalent of more than $1 billion a year. He was famed for violence and excess—sporting diamond pinkie rings and belt buckles, spending thousands on custom suits, and ordering hundreds of murders, likely including the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

But Capone’s later years were a far cry from his heyday, which once found his men kidnapping jazz legend Fats Waller and forcing him to perform at Capone’s three-day-long birthday party, before sending the composer and pianist home with pockets full of $1,000 bills. At the end of his life, Capone was incapacitated by neurosyphilis, and slipped in and out of lucidity. It’s these later years portrayed in the new film from director Josh Trank, Capone, which stars Tom Hardy as the ailing mobster. Here’s what you should know about the real-life gangsters final years.

Capone contracted syphilis while he was still a teenager.

Al Capone was married to his wife, Mae (played in Capone by Linda Cardellini), for all of his adult life, but was far from faithful and had many affairs and frequented prostitutes throughout his years in organized crime. But Capone contracted the syphilis that later killed him while still a teenager, perhaps from a sex worker at the docks in his native Brooklyn.

Alexander Fleming’s 1928 discovery of penicillin laid the groundwork for syphilis to become the highly-treatable infection it is today. But before an effective treatment was identified, syphilis was a “most foule and most grievous disease,” as one German scholar wrote of an outbreak in medieval Europe. Modern strains of the illness are not as lethal as those that swept communities hundreds of years ago, and are marked by three stages. In the first, people develop a chancre at the inflection point. The second stage is marked by a rash and patients can develop flu-like symptoms. In a minority of patients, the illness can re-emerge decades later, causing brain damage—neurosyphilis—and death.

That’s what happened to Capone. It’s possible that the illness had already begun to affect his cognition near the end of his time as a crime lord—Deirdre Bair notes in her 2016 Capone biography that, during the tax evasion trial that led to his downfall, he was already more subdued than gregarious figure the public had previously known. It’s been rumored that Capone didn’t seek treatment due to a fear of needles, but according to Bair, that’s pure myth, as he later underwent procedures like lumbar punctures that would have been impossible to imagine a patient with that particular phobia undergoing.

His health degraded dramatically over the seven years he spent in prison. Though Capone spent a year in Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary living in luxury with a $500 dollar top-of-the-line radio (more than $7,500 in today’s money) and a mattress imported from his home, he was afforded far fewer special privileges during his final prison term. In 1934, he was transferred to the newly-opened Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary, placing the nation’s most famous criminal in its toughest prison. There, he was stabbed by a fellow inmate and received generally inadequate medical care, developing sores on his face as well as a limping gait as signs of his advancing illness.

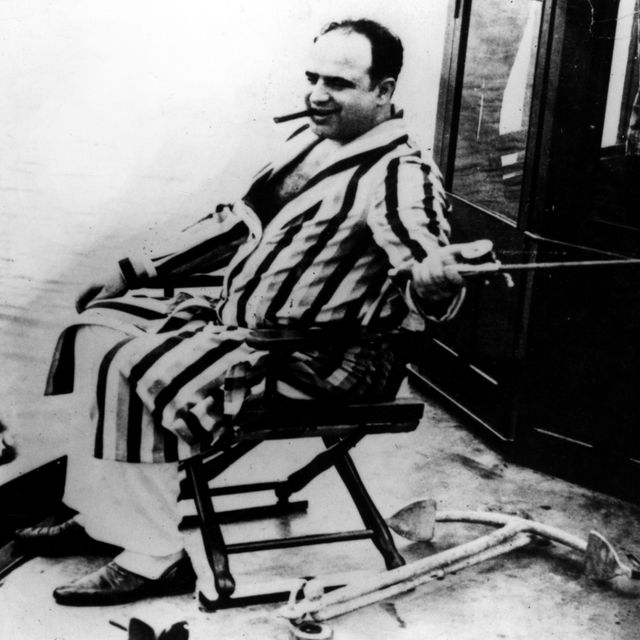

He was paroled in 1939, and returned to his home in Florida, where he was largely cared for by his family. By the time of his release, doctors estimated that he had the mental capacity of a seven-year-old, though his capability fluctuated under his improved care. His was a largely isolated life, in part because as his dementia worsened, he was prone to talking to people he’d ordered murdered and spilling organized crime secrets.

As depicted in Capone, he was monitored by federal agents in his final years, though Kyle MacLaughlin’s spying doctor is fictionalized character. (“There are similarities to the real-life doctor, but I have absolutely no evidence whatsoever that he had some sort of deal with the FBI,” Trank told Esquire.) And it was rumored that he played up his symptoms in front of outsiders in order to convince the authorities that pursuing him wasn’t worth their time, rumors that some of his relatives confirmed to Bair.

On January 21, 1947, Capone began having seizures. He died on January 25, at the age of 48.

Rumors of buried treasure have lingered in the decades since his death.

Though Capone and Mae were being supported by his brother during the kingpin’s final years, rumor spread that he had hidden substantial amounts of money away and had forgotten the location of the buried treasure. His lawyer denied the rumors, and Capone’s survivors lived modestly after his death. But tales of hidden millions—aided by the fact that in his prime the kingpin was said to be fond of fitting his headquarters and hideaways with secret tunnels and rooms—persisted.

In 1986, one of Capone’s former base camps, the Lexington Hotel in Chicago, was being renovated, and its owner agreed to tear down a wall surrounding one hidden underground room during a live television special hosted by Geraldo Rivera. The event promised that concealed loot or victims’ bodies might be uncovered, and attracted 30 million viewers. But when the wall was demolished after two hours of primetime TV anticipation, little more than some empty bottles were found. The opening of “Capone’s vault” would become infamous as one of the biggest fiascos in television history.

But speculation about secret loot continues. In 2019, a Chicago restaurant reported discovering a bricked-over vault in the basement of its building, which once belonged to a Capone enforcer. There’s no word on whether that vault has yet been opened. Capone’s great-niece told British tabloid the Daily Mail in the same year that she believes that her late uncle stashed more than $100 million in various secret locations that he forgot due to dementia. More than 60 years after Capone’s death, it doesn’t look like the tales of his hidden treasure are dissipating.