Looking Back at the Poster Girl Who Made Fine Art From ’90s Skating Culture

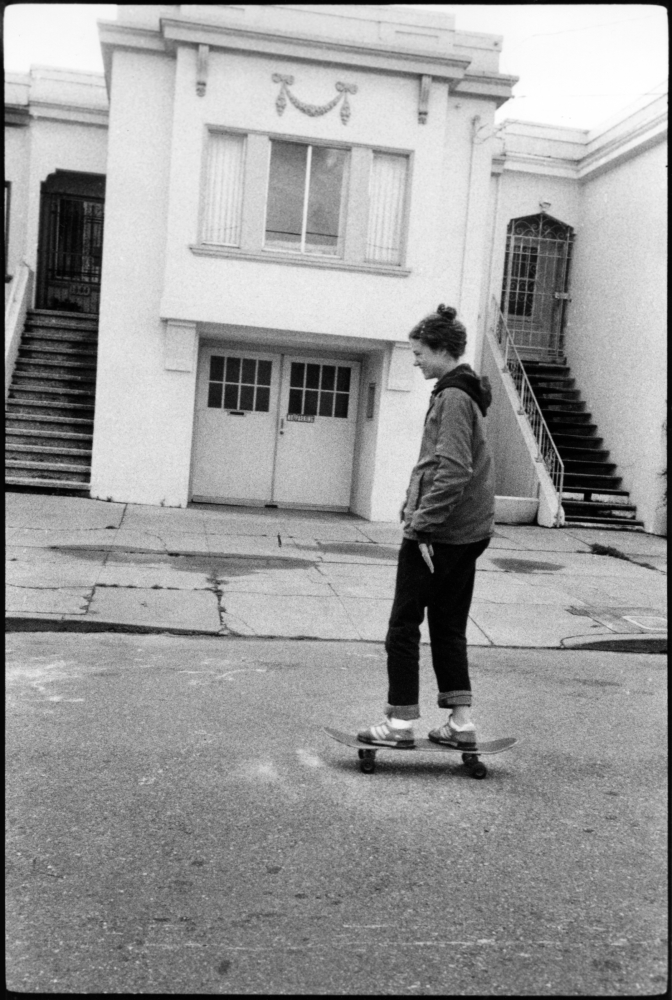

Margaret Kilgallen, photographed by Deanna Templeton in 1998.

Margaret Kilgallen wasn’t afraid to have fun. In the late artist’s expansive, color-saturated murals, cartoonish women tower alongside lollipop trees and glide through a landscape of skater-surfer lexicon — “Cheater Five,” “Let It Ride” — rendered in carnivalesque typography. At age 33, two weeks after giving birth to her daughter with husband and artist Barry McGee, Kilgallen died of breast cancer, just as her work was gaining prominence in the art world. A new exhibit at the Aspen Art Museum, that’s where the beauty is., celebrates Kilgallen’s folk-infused aesthetic, and her unique place within the history of feminist art. On view until June, it’s the first museum exhibit to commemorate Kilgallen’s work since her passing in 2001. In honor of the exhibit, we spoke with two photographers, Ed and Deanna Templeton, long time friends and champions of Kilgallen and her husband’s work. The Templetons, a married couple who have been collaborating since their early days shooting punk shows and making zines, are widely credited with merging skate culture and the contemporary art world. All together, the creative couples were core members of the ’90s skater-artists collective known as the “Beautiful Losers.” The Templetons reflected on their days with Kilgallen, as well as her undeniable, and under-recognized, influence on a generation of skaters and artists.

———

DEANNA TEMPLETON: I first met Margaret with Barry [McGee] back in 1997, when Aaron Rose was doing a group show at Alleged Gallery. We always did things as couples: Ed and I, Barry and Margaret. We live down in Southern California, and they were up north in San Francisco. When they would come down to LA to do some work, we’d would meet up with them for dinner, or sometimes we’d just sit in our car for hours talking.

Besides Ed, I didn’t really hang out with many artists at that time. I was intimidated. When we first met Barry and Margaret, it was at the Independents show in New York — I wasn’t a part of it, but Ed was, and I was helping him set up. We decided one day to go to this film festival, and we saw this Matthew Barney film. I’m sure it was only two hours, but it felt like it was a 10-hour movie. We were just like, “What are we watching?” But we sat there because we wanted to hang out with Barry and Margaret and they seemed like really cool people. So when the movie’s over, one of them broke the ice and asked, “What did you guys think?” We were like, “Well …” And they said: “We hated it.” And we were like, “We hated it too, we wanted to leave!” I remember Barry and Margaret said, “We didn’t want to look stupid in front of you.” From that point on, we saw them not just as incredible artists, but incredible human beings. I was just in awe of Margaret. She was so cute, she would always be on her bike, biking everywhere.

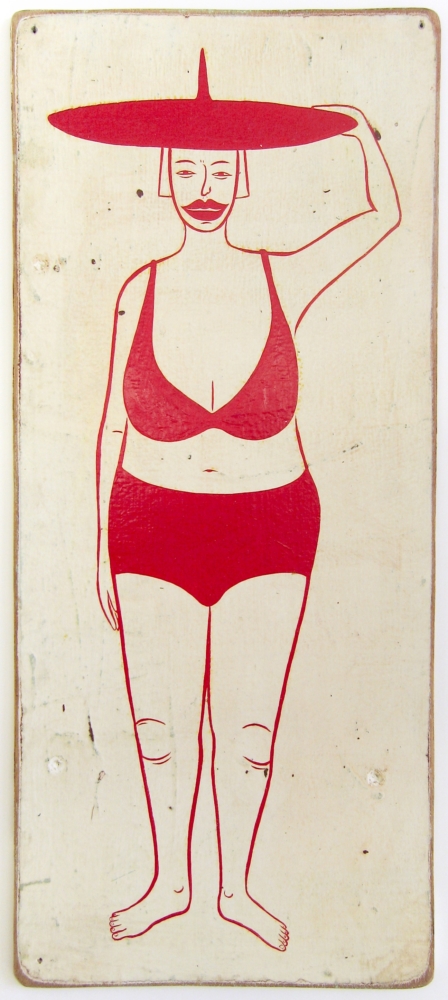

Margaret Kilgallen, Untitled, ca. 1999. Courtesy the Estate of Margaret Kilgallen and Ratio 3, San Francisco.

ED TEMPLETON: She rode from the Mission on her bike to meet us one night, and then refused a ride home afterwards because she wanted to just ride through the city by herself.

DEANNA TEMPLETON: She wrote me a very kind letter saying that I put her on a pedestal — that she wanted to be equals, but it made it harder for her that I was always acting like she was a goddess or something. She could tell I was lacking in self-confidence, unsure of myself and where my place was. At this point, I’m taking photos, but I’m not really out there showing my work. Ed was already on the roll, getting established. Margaret’s show at the Hammer in LA was incredible. David Hockney showed up to the opening, which was like, “What?”

ED TEMPLETON: Margaret embodied such a cool artistic sensibility. The way she held herself was very humble, but she projected her strength through her artwork. Even walking down the street, she would do tags in broad daylight. You think of graffiti artists as being sneaky, but watching her and Barry work, as we just walked down the street, she would just choose a parking meter randomly and draw “Meta” on it. It was almost a matter-of-fact thing: “I’m just doing this.” I think they had realized that when you’re doing something, anything, trying to hide yourself is even more suspicious than just doing it. Of course, especially as a woman dressed how she was, you wouldn’t probably ever suspect her as being a graffiti artist.

DEANNA TEMPLETON: All of them were doing something, and I was just trying to figure it out. She saw all that. I would get little letters from her, little notes here and there throughout the year, just checking in on me. She sent me my first book on Gloria Steinem. She opened my eyes to a way of seeing women out in the world. There was a seed planted, but it’s subtle and quiet when it comes up. I’m currently working on book that collects my 20 years of photographing young women, and I’m wondering if Margaret is the reason I’ve gravitated this way. After meeting Margaret, if I noticed anyone wavering, I would just back off. Part of me now thinks about what Margaret would say to me, “You have a voice.”

Margaret Kilgallen, Untitled, circa. 1999. Courtesy the Estate of Margaret Kilgallen and Ratio 3, San Francisco.

ED TEMPLETON: I think Margaret’s influence on my generation of artists, and the subsequent generations, is nearly unmeasurable. She stood as the poster woman for the whole generation. I just see it in the fashion, in the style, in the colors that people use now. You can almost directly draw a line back to Margaret. I see young skater girls, and they remind me of mini-Margarets.

DEANNA TEMPLETON: When we visited Barry and Margaret after she was diagnosed with breast cancer, she showed us the scars from the situation. It was very intimate. Seeing the love in Barry’s eyes when she talked about what was happening to her body — I don’t think I’ve ever seen such love than I did that moment when he looked at her. It will always stay with me. She and Barry had wanted a child for a while, and then she became pregnant. When she found out the cancer came back, she basically had a choice to make: you either end the pregnancy and start the chemo, or finish the pregnancy, and that’s it. She was out on the East Coast when she started to get sick again, and Barry was in Venice, Italy at the Biennale. From what we heard, she didn’t want to let him know she wasn’t feeling well because she wanted him to finish.

ED TEMPLETON: After her breast cancer, she was so careful in what she shared and how she shared it, even to people like me and Deanna, who were pretty close friends to both her and Barry at the time. You could see her hesitance in sharing.

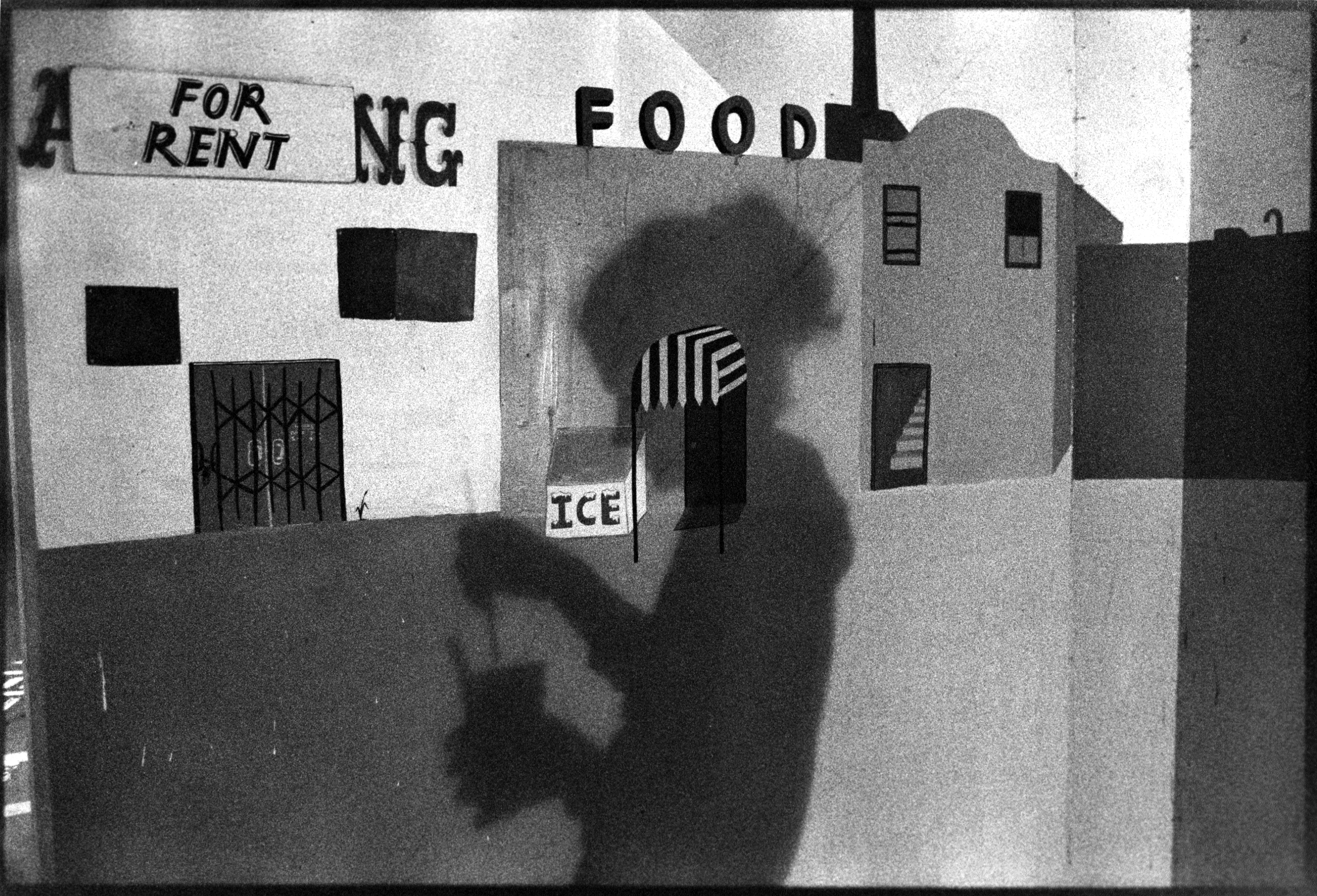

Margaret Kilgallen painting a mural at the LACMA garage in 1999. Photo by Ed Templeton. “It’s like the ghostly image of her,” Deanna says of the photo.

DEANNA TEMPLETON: I think Cheryl Dunn has these photos of Margaret painting when she was nine months pregnant. She was working up until the end. Two weeks after she gave birth to her child Asha, she passed. We were traveling around Europe when we got the news, and we decided to go visit Barry and see his work. He was part of a show called Street Market, with ESPO [Stephen Powers] and Todd James. There was so much Margaret in that show. Barry’s portion was just a love letter to Margaret. It was heartbreaking.

ED TEMPLETON: The work was littered with tributes to Margaret, photos of Margaret, references to Margaret. We were just both completely in tears walking through that show. It was really overwhelming — especially in light of the news that we had just heard. I think that we’ve all tried to frame her life as a celebration, rather than a tragic loss. But it was hard also not to see it as a complete loss to our community. One of the pillars of our group of people, artists, friends, whatever we were. For Margaret to be gone cracked the façade.