Case

A 24-year-old man was brought to the ED by emergency medical services (EMS) for altered mental status. The EMS crew reported they had picked up the patient at a nearby arts festival and concert series. A bystander at the event reported that the patient had taken something called “dragonfly.”

Initial assessment revealed the patient to be disoriented, with nonlinear thought patterns and an inability to follow commands. His vital signs were: blood pressure, 160/100 mm Hg; heart rate, 120 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; and temperature, 102.2˚F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. He was diaphoretic and agitated, and the nursing staff was concerned he would become aggressive and potentially violent. A quick Web search revealed that the agent the bystander mentioned was most likely Bromo-DragonFLY (BDF).

What is Bromo-DragonFLY?

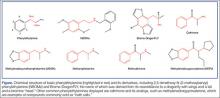

In the 1960s, an American chemist named Alexander Shulgin ushered in a new era of psychedelic drug use by establishing a simple synthesis of 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA). Following this discovery, he suggested a therapist friend use the drug therapeutically.1 Shulgin then began a process of homologation (ie, creating novel compounds by slightly altering existing ones in an organized fashion) and developed systems for rating the drug experiences and naming the drugs in shorthand, both of which are still in use. The chemical structure common to nearly all of the drugs he studied is phenylethylamine. The Figure shows the structures of several phenylethylamine derivatives that were created by adding functional groups to the phenylethylamine backbone. Although the popularity of psychedelic drugs surged during this time period, 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)phenylethylamine) (NBOMe), one of a number of newly popular psychedelics, only became available in 2003.

What is known about the pharmacology of Bromo-DragonFLY and NBOMe?

The major target of psychedelic drugs is the serotonin (5-HT2) receptor, specifically the central 5-HT2A subtype. Bromo-DragonFLY is a classic example of designer pharmacology in that the it was intended to potently exert its effect at this specific receptor site.

As its name suggests, BDF adds the “wings of the fly” to the phenylethylamine backbone furanyl rings at positions 2 and 5, and a halogen (bromine) at position 4. The furanyl ring impairs enzymatic clearance of the drug,2 resulting in a duration of action of up to 3 days.3 The addition of halogens increases drug potency, but the mechanism is not clear. The psychedelic agent NBOMe results from chemical additions of methoxy groups at position 2 and 5, and the halogen moiety (iodine in this case) at position 4 of the phenyl ring of the phenylethylamine structure.4

Through the work of Shulgin, some of his colleagues, and many disparate street chemists, a vast family of substituted phenylethylamines have been synthesized and used. Shulgin’s semiautobiographical book PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story includes his laboratory notes for the synthesis and initial test-dose experience of 179 compounds1; this does not include research done by others or any work since its publication in 1995.

Notable popular drugs chemically similar to NBOMe and BDF are mescaline (found in peyote), cathinones (“bath salts”), and MDMA (found in ecstasy) (Figure). Naturally occurring (and more complex) compounds with similar effects include ayahuasca, a plant-derived beverage consisting of Banisteriopsis caapi and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana from the Brazilian rainforest (see Emerg Med. 2014;46[12]:553-556); psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”); and lysergic acid diethylamide.

How are these drugs used and what are their clinical effects?

Most phenylethylamine compounds are well absorbed across the buccal mucosa, which is why BDF and NBOMe are commonly used in liquid form or on blotter paper. Dosing guides also exist for insufflation and claim equipotent dosing for this route.5 Regardless of delivery route, given the high potency, inadvertent exposures to these drugs should be expected.

Users simply seeking to hallucinate may not be aware of the significant risks associated with these potent serotonergic agents, which include both life- and limb-threatening effects.6 The high 5-HT2A potency results both in vasoconstriction and promotion of clot formation due to the presence of 5HT2A receptors on small blood vessels and platelets, respectively. Ergotism, historically called Saint Anthony’s fire, is an example of serotonergic vasoconstriction and hallucination.7 Chronic users of substituted amphetamines can develop necrotic ulcers in distal vascular beds such as the hands and feet; these ulcers may progress to amputation despite treatment attempts with vasodilators.

In addition to the vasoconstrictive properties, there are multiple reports of serotonin toxicity (serotonin syndrome) associated with use of these designer serotonergic amphetamines. This syndrome includes severe psychomotor agitation that can lead to personal injury, along with muscle rigidity, tremor, hyperthermia, rhabdomyolysis, and seizures.8