Abstract

Hārītī is the first female deity in Buddhism that was credited with responsibility for protecting women during childbirth and protecting children. Since her introduction to China from India, her image has undergone multiple changes, and the rise and fall of her cult is closely related to the social culture around her reception. However, previous research on Hārītī has focused mainly on historiographical aspects, and little attention has been given to image evolution after her introduction into China. Therefore, this paper mainly utilizes iconographic methods to systematically review the characteristics of Hārītī’s image in different periods and investigate the social causes and religious meanings behind her evolution. The study revealed that the image of Hārītī has experienced five development phases: Hellenization, Sinicization, demonization, confusion, and parasitization. The most fundamental reason for her rise in China was the strong demand for fertility among the people. The most important reasons for her decline in China include the deep-rooted negative popular view of her yaksha identity and the prevalence of images and stories of the child-giving Avalokitesvara, who replaced her core functions entirely. In this way, Hārītī worship underwent gradual marginalization in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Chinese, Hārītī is Guizimu鬼子母 (Mother of Demon Children), Jiuzimu九子母 (Nine-son Mother), Helidi訶利帝, and Helidinan訶利帝南; “Guizimu” is the most popular termFootnote 1. According to the Buddhist sutras translated into Chinese, she acquired the name “Guizimu” because she gave birth to many demon children (Hsuan, 2009, p. 369). She first appeared in Gandhara, India, as a yaksha, an Indian semigod and semidemon. People fearfully dubbed her the “demon of sickness of smallpox” due to her dedicated use of the smallpox virus to harm local children (Madhurika, 2009, p. 402). Afterward, out of the fear of her supernatural powers and for the sake of children’s immunity from smallpox, they enshrined Hārītī and called her “smallpox goddess” (Foucher, 2008, p. 248). In the long run, Hārītī has been gradually transformed from a negative and malignant deity into a positive and revered patron and protector.

Since the introduction of Buddhism into the Gandhara region, Hārītī has been incorporated into the Buddhist system of deities as a yaksha. In Buddhism, Hārītī rejected wickedness and evil and embraced virtue through the guidance of the Buddha (Yuan, 2017, p. 30). Subsequently, she converted to Buddhism and became the first goddess in Buddhism to pledge herself to protecting pregnant and postpartum women and their offspring (Li, 2016, pp. 82–96; Art Research Academy of Shandong Arts College, 2020, p. 51). Due to her contradictory status, as a half-goddess and half-demoness, Hārītī has received increasing attention from scholars, and from classic information, research findings have mainly concentrated on three aspects: story compilation, origin and dissemination, and relationship analysis.

First, the story compilation is related to Hārītī, which focuses primarily on the themes of predestination, role identities, the number of ghost children, and other related topics. The book falls into two categories according to the nature of the literature: the first is Buddhist scriptures, among which the most important is Mūlasarvāstivādah-vinaya-sudraka-vastu (Genbenshuo yiqieyoubu pinaiye zashi根本說一切有部毗奈耶雜事), written by the monk Yijing in 703. This text contains the records of her name origin, motivation for eating humans, the reception of teachings from Buddha and other topics related to Hārītī in Volume 31; this translated scripture, which relates the stories about Hārītī, is the most complete (Shi, 1412–1417). The Sutra of the Demon-mother told by the Buddha (Foshuo Guizimu jing佛說鬼子母經) (Anonymous, 1412–1417), another scripture transcribed by an anonymous translator in the Western Jin Dynasty 西晉 (265–316) is currently the earliest known Buddhist classic translated into Chinese concerning the Hārītī belief, and the text includes the occurrence of time, her role identities, the number of ghost children and the religious duties in stories about Hārītī. Most importantly, this scripture indicates that mundane duties such as sending children to people trying to become pregnant, safeguarding property and aiding in childbirth are the primary driving forces behind the extensive spread of Hārītī stories in folk medicine (Anonymous, 1412–1417). Subsequently, the Samyuktaratnapitaka-sutra (Za Bao Zang Jing 雜寶藏經), which was translated in the Northern Wei 北魏 (386–534), offers a comprehensive account of Hārītī’s conversion to Buddhism (Li, 2006, pp. 178–179). The second major category of literature is secular writings. Mingxiangji 冥祥記 is one such example, in which Wang Yan 王琰 recorded a man named Zhang Ying 張應, who enshrined Hārītī and prayed for her blessing to cure his wife, indicating that the Hārītī belief was known among the people living south of the Yangtze River in China before and after the fourth and fifth centuries (Wang, 1956). Moreover, the Records of Jingchu (Jingchu Suishiji 荊楚歲時記) (Zong, 1987) by Zonglin 宗懍 and the Miscellaneous Dhāraṇī Collection (Tuoluoni Zaji 陀羅尼雜集) (Anonymous, 1645–1911) by an anonymous translator both described the prevalence of Hārītī belief in southern China.

Second, there is research on the origin and propagation of beliefs around Hārītī. In terms of her origin, Shūyū Kanaoka expounded upon the legend of Hārītī and indicated that the complete myth finally came into being in India in the first half of the fifth century (Kanaoka, 1985); Muvaliura Khan held that the goddess “Bahula” in Sanskrit refers exactly to Hārītī, which indicates that Hārītī is a female deity in charge of reproduction, fortune, and agriculture (Khan, 1997). Gregory Schopen revised the opinion of his predecessor Peri and indicated that Hārītī protected children because monks first protected her 500 demon sons (Schopen and Gomez, 2014).

For the propagation of her stories, Zhao Bangyan 趙邦彥 conducted textual research on the Han Shu 漢書 (The History of the Han Dynasty) and found that with the introduction of Buddhism into China in the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220), Hārītī might have entered with other Buddhist sutras (Zhao, 1935). Ming-Liang Hsieh 謝明良 identified a ceramic human-shaped lamp and a nine-son stone relief, both from the Han Dynasty and which were unearthed in Henan and Shandong, respectively, as Hārītī, since both have the facial features of the Hu people. Hsieh proposed that the introduction of Hārītī beliefs and images into China might be related to the nomadism on the part of the Sakas (Hsieh, 2009). Yuan et al. focused on the propagation and transformation of Hārītī, indicating that she acquired local names and portraits as a native after being converted to Buddhism, demonstrating the gradual cultural integration of Hārītī into the traditions in China, Japan, Vietnam and other countries (Yuan, 2011, pp. 117–205).

Finally, there is research on the relationships of Hārītī to other figures in Buddhism. Foucher initially discussed the relationship between Hārītī and China’s Guanyin 觀音, who is also known as Avalokitesvara in Sanskrit. This study provided a new perspective for subsequent research by proposing a series of questions, such as whether the personality traits of Hārītī were grafted onto a native counterpart. Additionally, were these characteristics incorporated into the model of the female Guanyin so that she might be considered one of her multiple incarnations? (Foucher, 2008, pp. 4–29) Afterward, Dore (1920, p. 203), Getty (1914, p. 75), and Du et al. (2017, p. 9) 杜陽光 explored the transference of Hārītī’s image and functions to the child-giving Guanyin. Xiang Yurong 項裕榮 indicated that Jiuzimu 九子母 was another translated term for Hārītī. However, due to its noninterchangeability in Buddhist classics, the name was gradually localized by Taoism, which was on the rise (Xiang, 2005, pp. 171–181). Moreover, Richard S. Cohen emphasized the coordination among monks through the worship of Hārītī and the interrelationships between Buddha, gods and spirits, and monks in space (Cohen, 1998, pp. 360–400).

In brief, previous research covered a diverse range of topics on the origins, arts, relationships, and other aspects of Hārītī. However, in China, as a country with a rich cultural and religious history, the belief and image of Hārītī are inevitably subject to complex and multifaceted influences. The current discussion on the issue of Hārītī’s Sinicization is insufficient and involves some essential topics, such as the localization of foreign religious images and the secularization of beliefs. Therefore, it is imperative to initiate a comprehensive discussion on this matter.

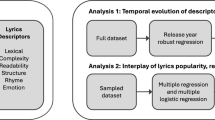

This paper mainly discusses the rise and fall of Hārītī in China and the causes behind this phenomenon. Idol worship is a significant facet of religious practices whereby sculptures of religious figures provide a tangible form for idol worship. Hence, the first part of this paper primarily uses iconological methodologies to review the transformation of Hārītī’s image and divides her changes in imagery into five phases: an initial Hellenistic style during the Gandhara period; the Sinicized period from the Wei-Jin to the Tang Dynasty; a demonized style in the Song Dynasty; a confused style in the Ming and Qing periods; and, finally, a parasitized style after the Ming and Qing periods. The second part of this paper analyzes the reasons for the changes in the characteristic imagery and identity of Hārītī. First, the reasons for the boom of Hārītī worship in China are discussed from the perspectives of the functions of foreign gods and native demand. Second, Avalokitesvara is introduced as a comparative figure to analyze the causes of the fall of Hārītī in China.

Evolution of images of Hārītī in past dynasties

Hellenistic images of Hārītī in the Gandhara Period

The statues of Hārītī during the Gandhara period were influenced by Greek culture, and their styles borrowed ideas from the image of the Greek goddess of a bountiful harvest to present physical characteristics such as a plump figure, elegant movements, and soft, gentle facial expression. The most typical depiction of the harvest goddess includes her holding a cornucopia (Sun, 2019, p. 93). In Greek myths, the cornucopia implies the horn of the goat that suckled Zeus and is filled with flowers and fruits to represent opulence and fortune.

Initially, the depictions of Hārītī were modeled on the goddess of the harvest, who also held a cornucopia, and Hārītī and her husband often appeared as a couple. For example, in the sculpture of Teaching Buddha with Hārītī Consorts, made in the 2nd–3rd century, an image combining Hārītī and her husband appears on the pedestal, with Hārītī holding the cornucopia in her left hand and her husband holding a long spear in his right hand (Fig. 1). In the 5th-century sculpture of the Buddha at the Great Miracle, Hārītī is holding a cornucopia to the left of the Buddha, while her husband appears to the right in the form of a male deity (Fig. 2). This type of image, comprising Hārītī holding a cornucopia and her husband appears beside the Buddha as a symbol of fortune.

Materials: parcel-gilt and polychrome schist. Dimensions: H. 51 cm. Photo source: official website of the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film ArchiveFootnote

Teaching Buddha, Gandhara. https://bampfa.org/divine-women-slideshow. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

.Materials: Shale with traces of gilding. Dimensions: H. 81 cm. Housed in the Musée national des Arts asiatiques-Guimet, Paris, France. Photo source: official website of the Musée national des Arts asiatiques-GuimetFootnote

The Buddha at the Great Miracle. https://www.guimet.fr/collections/afghanistan-pakistan/le-buddha-au-grand-miracle. Accessed on 2 August 2023.

.Over time, new styles of Hārītī statues appeared that had no cornucopia but were accompanied by children. These statues of Hārītī retained the image of the harvest goddess and were usually depicted as holding children or being surrounded by them below knee-height. For example, in the statue of the Buddhist Goddess Hārītī with Children, Hārītī exposes her chest and abdomen, and her hair is gathered up in a bun. She holds a child before her breast, with one kneeling on her left shoulder, two lying by her right foot, and one sitting upright between her feet (Fig. 3). Hārītī’s imagery with the addition of child elements reflects the transformation in her identity before and after her conversion to Buddhism, from a pestilence goddess of smallpox to a Buddhist deity responsible for childbirth and protecting children.

Materials: gray phyllite. Dimensions: H. 110.49 cm × W. 35.56 cm × D. 15.24 cm. Housed in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, United States of America. Photo source: the official website of the Los Angeles County Museum of ArtFootnote

The Buddhist Goddess Hārītī with Children. https://collections.lacma.org/node/239439. Accessed on 2 August 2023.

.The transition of the portrayal of Hārītī following her incorporation into Buddhism was principally intended to project Buddhism’s supremacy over other deities and at the same time highlight the Buddhist belief in karmic results. This can be observed in the story of the Buddha subduing Hārītī following karmic causes and conditions. Hārītī, who was then pregnant, was on her way to a meeting to worship the Buddha in Rājagriha, but she miscarried halfway through the pilgrimage and was left behind by her 500 companions, who had all moved on. Then, Hārītī offered 500 fruits to the Buddha and swore to eat all the children in the city as revenge. Afterward, Hārītī was reborn in Rājagriha, gave birth to 500 offspring, and preyed upon other children in the city. Buddha eventually reformed her into a Buddhist patron deity for children by hiding one of her children. Due to the Buddha’s decree, Hārītī’s image was placed in every Buddhist monastery, and food was offered to her at each mealtime as a ritual. This practice established her as the Buddhist guardian deity for children (Shi, 1412–1427). Viewing this karmic story from a more remote vantage point, the subduing of this foreign yaksha highlights the triumph of Buddhism. At the same time, Hārītī’s birth to 500 offspring resulted from her offering of 500 fruits to the Buddha, her evil wish to devour children, and her 500 fellow travelers abandoning her at the moment of her miscarriage. In other words, the myth of Hārītī was the integration of Buddhist expansion and the doctrine of causation.

It is noteworthy that Xinjiang 新疆 was the place where Hārītī first arrived in China, where the statutes of Hārītī were consistent with the patterns of Gandhara. To illustrate this phenomenon, in the Fresco of Hārītī in Hetian和闐, Xinjiang, the figure of a goddess stands in the center of the image, surrounded by children. She possesses “perforated and frightfully distended earlobes,” along with voluptuous folds on her neck and the distinctive “triple circular orb of the nimbus,” representing the typical Sogdian style once prevalent among the Sogdian inhabitants of the Gandhara regions (Fig. 4) (Foucher, 2008, pp. 285–287). Such a painting indicates that the image of Hārītī did not undergo significant changes in the early years after her belief was introduced into China.

Dimensions: H. 61 cm × W. 61 cm. Housed in the National Museum, New Delhi, India. Photo source: the official website of the Chughtai MuseumFootnote

Tempera painting of Hārītī. http://blog.chughtaimuseum.com/?p=2824. Accessed on 2 August 2023.

.Sinicized images of Hārītī during the Western Jin Dynasty and Tang Dynasty

During the Western Jin Dynasty (266–420), the belief in Hārītī began to flow into mainland China with the spread of the Buddhist classics translated into Chinese. Meanwhile, Hārītī, gradually developed from the Greek harvest goddess image to an image characteristic of Chinese women, presenting a developmental trend towards Sinicization. Cave No. 9 of the Yungang 雲岡 Grottoes contains the oldest existing material object representation of Hārītī (Fig. 5), which appeared in the early reign of Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei (484–489) (Su, 1996, p.79). Hārītī’s hairstyle in sculpture retains the Indian style of curly hair, but her figure and facial features already show the traits of a Chinese celestial maiden.

By the Tang Dynasty (618–907), with the rapid spread of the belief in Hārītī, she had been Sinicized in figure modeling. For example, in the Tang Hārītī statues No. 68 and No. 81 in the southern niches of the Bazhong 巴中 Grottoes, Hārītī is seated in the center in a long dress, with a plump face typical of a Tang woman, wearing a pie-shaped bun on her head and embroidered shoes (Xiuhua Xie 繡花鞋). She holds a young child in her arms, with four others scattered by her sides in various postures. The children’s hairstyles are all typical of Chinese hairstyles (Fig. 6). In brief, the images of Hārītī and the children display typical Tang characteristics of physiognomy, haircut, and costume.

The number of children in these statutes is always nine. Why does this phenomenon occur? This can be traced back to the Nine-son mother, or Jiuzimu 九子母 in Chinese, a local Chinese deity.

The Nine-son mother is an indigenous Chinese fertility goddess. While some scholars claim that the concept originated in India (Wen, 1985, p. 79), others have disproved this theory (Li, 2002, pp. 33–40; Long, 2003, pp. 137–142). In fact, the Nine-son Mother evolved from the indigenous Chinese Nine-son Star (Jiu Zi Xing 九子星) of the Twenty-eight Mansions (Er Shi Ba Xingxiu 二十八星宿)Footnote 6Since the Nine-son Star is characterized by numerous offspring (Fang, 1974), the Nine-son Mother is imbued with the significance of worship around themes of childbirth. In the pre-Qin先秦 period, the homophony between 九 (Jiu, nine) and 鬼 (Gui, ghost) led to confusion between 鬼子母 (Guizimu, Hārītī) and 九子母 (Jiuzimu, Nine-son Mother) when used as appellations, to the extent that they even became one after the Tang Dynasty (Yang, 2012, pp. 39–42). This confusion led to the finding that the Tang people called the Nine-son Mother the Nine-son Demoness Mother (Jiu zi mo mu 九子魔母) (Meng, 1957, p. 24), which had never been recorded before. As recorded in the history of ancient paintings, when the artists of the Tang Dynasty depicted this theme, they sometimes used the term “Guizimu” and sometimes the name “Jiuzimu.” Moreover, one of the remarkable characteristics of Jiuzimu is her depiction with nine children (Yue, 2007, p. 3255), from which one can deduce that the pattern of the nine children surrounding the Hārītī sculpture may have been influenced by the imagery of the Nine-son Mother.

The compositional pattern featuring nine sons encircling Hārītī has significantly influenced subsequent Hārītī sculptures and paintings, not only in Xinjiang and Yunnan but also in Japan. For instance, the 9th-century murals in the Kizil Caves in Turpan portray the scene of nine sons encircling Hārītī (Liu, 1996, p. 38). Scholarly research suggests that the depiction of nine sons is absent from Indian or Central Asian Buddhist art. This suggests that the depiction of Hārītī in the Turpan region was likely influenced by Buddhist art in the Tang Dynasty capital, Chang’an (Murray, 1981, pp. 253–284; Soper, 1960, pp. 33). Additionally, Zhang Shengwen, a painter from Dali, Yunnan, presented a more detailed portrayal of Hārītī surrounded by nine sons in the Sanskrit Image Volume (Fan Xiang Juan 梵像卷). Additionally, the Taisho Tripitaka, a collection of esoteric Buddhist scriptures in Japan, features depictions of Hārītī in a style similar to that of Zhang Shengwen’s work from a contemporaneous time period (Yuan, 2017, p. 33). These examples illustrate the profound influence of the Tang Dynasty version of Hārītī surrounded by nine sons.

In conclusion, from the Western Jin to the Tang dynasties, Hārītī’s image not only became more Sinicized but also integrated with Jiuzimu, the indigenous Chinese fertility goddess. This amalgamation resulted in a religious figure that could be more easily spread within China.

Demonized images of Hārītī during the Song and Yuan Dynasties

During the Song Dynasty (960–1297), segaki, the ritual of offering food and drink to ghosts and deities became widespread (Ma, 2004, p. 201). Hārītī, as the main recipient of these offerings, attracted attention, and her belief system gradually moved from temples to the general population and spread widely. Her stories became a popular theme in literary and artistic creations (Xia and Bao, 2017, pp. 52–58). In particular, the most dramatic part of the Hārītī narrative, the plot of Raising the Alms-bowl, or Jie Bo 揭缽, has been selected and artistically interpreted by individuals with striking expressive and conflicting artistry, making it emotionally resonant.

The theme of Raising the Alms-bowl depicts a story in which the Buddha traps the youngest son of Hārītī under an alms-bowl and Hārītī attempts to rescue him.

According to currently available information, there are more than 30 scrolls with paintings on the theme “Raising the Alms-bowl,” which are similar except for slight differences in composition and image and thus should derive from similar manuscript sources or copies (Murray, 1981, pp. 253–284). Among them, a relatively typical painting is “Raising the Alms-bowl” (Jiebo tu 揭缽圖) of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), which is preserved at the Palace Museum in Beijing. In the scene, Priyankara 嬪伽羅 (also known as Piyankara or Pingala), the young son of Hārītī, was encapsulated under a glazed alms-bowl in the center. Hārītī and several yakshas are on the right, Buddha is seated cross-legged on a lotus throne and guarded by dozens of divine generals. Priyankara cries for help under the bowl; Hārītī makes a distraught face, obviously mentally and physically exhausted by the rescue of her son. The yaksha demons are sinister in appearance and are busy with levering the alms-bowl with support. The Buddha calmly observes the demons uncovering the alms-bowl (Fig. 7).

Dimensions: H. 31.8 × W. 97.6 cm. Housed in the Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Photo source: the official website of the Palace MuseumFootnote

Jiebo tu揭缽圖. https://www.dpm.org.cn/collection/paint/228774. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

.Through the painting, we observe that the image and identity of Hārītī underwent a new transformation in the Song Dynasty. While still retaining the characteristics of Chinese women, depictions of Hārītī came to more closely resemble scenes in ordinary people’s lives, resembling a worldly mother who worried about her suffering child. This suggests that the image of Hārītī has become more secularized. Importantly, Hārītī, who had previously appeared at the side of Buddha as a Buddhist deity, now stood against him, presenting herself in an evil aspect as a yaksha, or female demon. This indicates that her yaksha identity and demonic origin are significantly emphasized, and she transforms into an object of entertainment for the public, gradually dissolving the solemnity of her religious goddess image.

The sculpture of Hārītī, conveying a similar meaning, emerged in the Shanhua Temple 善化寺 in the later Liao and Jin dynasties (Fig. 8). The sculpture depicts Hārītī wearing a long robe, standing with crossed hands, embodying the image of an imperial consort (approximately 3.72 m high). Beneath the left foot of Hārītī, there is a statue portraying her evil image, that is, a statue of a yaksha (approximately 1.4 m high) with a green face, red hair, a wide mouth, and a child in her arms (head now destroyed) (Yuan, 2011, pp. 31–47). It is evident that the ancient sculptors juxtaposed the yaksha’s short, malevolent, and ugly figure with the tall, virtuous, and beautiful image of Hārītī post-conversion to Buddhism (Niu, 2015, pp. 83–84), showcasing a clear influence from the Song Dynasty on images themes to Raising the Alms-bowl. This further implies the contradictory psychological effects of people’s need for Hārītī in bestowing and protecting children, along with the negative perception of her yaksha identity, laying the groundwork for her decline in China.

Dimensions: H. 372 cm. Located in Shanhua Temple, Datong, Shanxi Province, China. Photo source: the official website of wikipediaFootnote

Statue of Hārītī in Shanhua Temple. https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-cn/File:Statue_of_Hariti_(%E9%AC%BC%E5%AD%90%E6%AF%8D_Guizimu)_in_Shanhua_Temple_(%E5%96%84%E5%8C%96%E5%AF%BA_Sh%C3%A0nh%C3%B9as%C3%AC)_in_Datong,_Shanxi_Province,_China.jpg. Accessed on 8 December 2023.

.There are three distinct reasons for this change. First, the widespread ritual of segaki in Buddhism and the prevalent narrative of Raising the alms-bowl reinforced the popular perception of Hārītī as a yaksha. In these rituals and stories, Hārītī is portrayed both as a recipient of Buddhist alms and as a demoness in conflict with the Buddha. When people think of her, they often imagine not a serious and just goddess but an image of a humble demoness. Second, the economic boom and emergence of urban life in the Song Dynasty led to changes in social and ideological trends. The ideological enlightenment promoted the awakening of humanity’s consciousness, which dispelled the seriousness of religion. Thus, artistic works in genres such as drama and painting began to target and attack religious icons; the most easily mocked figure was naturally the yaksha-origin Hārītī (Li, 2018, p. 269). Third, the social status of women fell dramatically during the Song Dynasty due to the emergence of Neo-Confucianism 程朱理學. As indicated by Patricia Ebrey, the Song Dynasty was an era in which women’s situation observably deteriorated (Ebrey, 2004, pp.5–6). Practices such as requiring women to observe chastity, foot binding, and other phenomena were widespread. There was even advocacy that death by starvation was preferable to the loss of chastity. Some women from the lower classes were even required to learn to sing and dance from girlhood in preparation for selection by scholar-bureaucrats, who needed them for entertainment and service (Huang, 2005, p. 106). As a female deity, the situation for Hārītī worsened accordingly. Under the combined effects of the above factors, Hārītī fell from grace and was even categorized as a demoness, eventually being reduced to a target for entertainment. Her yaksha identity was emphatically highlighted, as she was eventually reduced to an object of mockery by the common people.

Confusing images of Hārītī during the Ming and Qing Dynasties

During the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1636–1912) dynasties, the image of Hārītī was mostly present in water-and-land paintings (Shui lu hua 水陸畫). Water-and-land paintings are decorative religious paintings indispensable for rituals involving water-and-land services (Shui lu fahui 水陸法會 in Buddhism held in China’s ancient temples). Water-and-land services emerged in Buddhism and peaked in the Ming Dynasty (Huang, 2006, pp. 102–122). The rituals of water-and-land services in Buddhism are important Buddhist ceremonies held by Buddhist temples; their primary purpose is to save all lost souls, ghosts and gods from the sea of miserable life and enable them to ascend to heaven with the help of the supernatural power of gods (Hou, 2022, pp. 60–65). In a Buddhist water-and-land service, rescuers and rescuees gather together, covering Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian figures, such as all buddhas and bodhisattvas, divinities, and figures of human society (Xu, 2017, p. 250). Therefore, the objects depicted in China’s water-and-land paintings are also all inclusive, covering many images of Hārītī, which can serve as essential materials for studying the spread of Hārītī’s images during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Hārītī’s images in water-and-land paintings were not uniform; instead, they developed into three styles. The Baoning Temple 寶寧寺 located in Shanxi Province 山西 has an old collection of water-and-land paintings, which are first-class cultural relics. Emperor Yingzong 明英宗 of the Ming Dynasty granted them to the temple during his reign Tianshun 天順 (1457–1465) to safeguard the frontier and release the souls of fallen officers and soldiers from suffering. This set of paintings is imbued with the Ming royal style in terms of brushwork, coloring, pattern, and size and is known as the “crown of eastern water-and-land painting” (Li, 2019, pp. 66–67).

These paintings portray three images of Hārītī (Fig. 9), each with an explanatory inscription.

-

(1)

The inscription in the first image reads “43rd on the left, Demoness Guizimu (Hārītī) and Rakshasa Deities” (Zuo di si shi san guizimu luocha zhushen zhong 左第四十三 鬼子母羅剎諸神眾). There are eight figures in the image, where Hārītī stands on the front line as a noblewoman, followed by an animal in the shape of a giant eagle carrying her son, then a maid, and four demons holding weapons.

-

(2)

The inscription in the second image reads “44th on the left, Helidi Mother and the Grand Rakshasa Deities” (Zuo di si shi si helidimu daluocha zhushen zhong 左第四十四 訶利帝母大羅剎諸神眾). There are ten figures in the image where Helidi Mother bears a resemblance to Hārītī, as she stands in front of the others with two maids by her side and seven Rakshasas following her, but no child (Shanxi Museum, 2015, p.192).

-

(3)

The inscription in the third image reads “18th on the right, Prthivi, Helidinan, and Other Deities” (You di shi ba jianlaodishen yu helidinan zhushen zhong 右第十八 堅牢地神與訶利帝喃諸神眾). Three figures are presented in the image. In front, two deities stand: Prthivi and Helidinan. One is holding a hu 笏, a tablet used for official audiences, while wearing a tongtian guan, which is a high crown. The other is a female celestial being wearing a hua guan 華冠, a crown resembling a spiral chignon, and wearing a Buddhist robe made of strings of jade and pearls. Walking behind them is an attendant, carrying a funeral banner. No children are visible in the painting.

a No 84, 43rd on the right, Demoness Guizimu (Hārītī) and Rakshasa Deities左第四十三 鬼子母羅剎諸神眾; b No 85, 44th on the left, Helidi Mother and the Grand Rakshasa Deities左第四十四 訶利帝母大羅剎諸神眾; c No 105, 18th on the right, Prthivi, Helidinan, and Other Deities右第十八 堅牢地神與訶利帝喃諸神眾. Materials: silk. Housed in the Shanxi Museum, Taiyuan, China.

Thus, in the water-and-land paintings, Hārītī embodies three forms: Hārītī (Guizimu), Helidi, and Helidinan.

Why does Hārītī in this set of water-and-land paintings have three images? Thus far, a scholarly consensus has been reached regarding the identities of Hārītī in these three paintings; namely, Hārītī, Helidi Mother, and Helidinan were originally one goddess. However, Hārītī’s identity was divided into three parts due to translation errors (Li, 2017, pp.82–98; Liu, 2023, pp. 100–125).

Shi Fayun 釋法雲 (1088–1158), a monk of the Song Dynasty, provided specific insight into this phenomenon: “The ‘Golden Light Sutra’ (Jin guangming jing 金光明經) says that Helidinan is a transliteration from Sanskrit, and Guizimu (Hārītī) and the like are the appellations in the dialect of Liangzhou. These two names refer to the same individual. Later summaries state that the residents of Rājagriha at that time referred to the goddess as the Helidi Mother deity (Fa, 1935, p. 53).” That is, Helidi is the transliteration from Guizimu, with Hārīti meaning Guizimu in Sanskrit, and Helidinan is the appellation of Helidi in the Liangzhou dialect (present-day Wuwei, Gansu Province), in which “nan” is a final syllable. The mixed use of these three translations resulted in discrepancies in the dissemination of the Hārītī concept among Chinese monks and laymen, which eventually caused confusion between Hārītī, the Helidi Mother, and Helidinan as three deities.

When such errors were demonstrated in images, Hārītī remained the guardian goddess of protected children and pregnant women. Therefore, a child was depicted in the images of “Demoness Guizimu (Hārītī) and Rakshasa Deities”. Two foreign gods, Helidi Mother and Helidinan, were portrayed without a child, indicating that they were new gods who had separated from Hārītī. Similar situations generally occur in the temple mural paintings of the Ming Dynasty. Within the Jingang Hall at Gratitude Temple 感恩寺, Yongdeng 永登, Gansu 甘肅 Province, two celestial gods, “Hārītī” and “Helidinan,” coexist in the chess eye mural paintings (Liu and Yang, 2014, p. 57). Similarly, in the existing frescoes of the Ming Dynasty located in Sichuan, these two were simultaneously portrayed as part of the Twenty-four Celestial Gods. In the frescoes in Pilu Temple 毗盧寺, a “Hārītī Deity” is depicted with children, and a “Helidi Mother Deity” is depicted without children (Liu and Yang, 2014, p. 208) (Fig. 10).

Through the depiction of the image of Hārītī in the water-and-land paintings of the Ming and Qing dynasties, one can find that, due to the misinformation and oversight of her religious identity, confusion begot three variants. Among them, Hārītī, who still undertakes caring for children, appears with children, while Helidi Mother and Helidinan, followed by no children, evolve gradually into symbolic patron saints.

The confusion in the folk transmission of the Hārītī belief, leading to such new creations, demonstrated a lack of attention given to the religious meanings hidden behind the gods and the details in their images on the part of most monks and believers. Having lost the looks of an offspring-bestowing goddess, which Hārītī had had in her earlier phase, Helidi Mother and Helidinan arose as symbolic Buddhist gods. This reflects the worldly and utilitarian purposes of believers in the worship of gods. People were concerned about whether they could be protected by worshiping these gods, and efficaciousness was at the core of folk belief. This behavior is consistent with a utilitarian mindset in which individuals unconsciously shape or adopt spiritual entities to meet their specific needs.

Hārītī’s images of parasitization in modern times

The images of Hārītī have gradually decreased since the Ming and Qing dynasties, but they have not vanished entirely. Traces of her presence persist in remote regions of China, such as Yunnan 雲南, Xizang 西藏, and Mongolia 蒙古. Her influence is particularly prominent in the beliefs of the Yunnan region. During the period of the Dali Kingdom, the belief in Hārītī was introduced into Yunnan in approximately the 12th century. She was first introduced to Dali, the capital of that time, and then radiated to its environs. In the process of her spread, beliefs about her were combined with local traditional religions and cultures to form a belief in Hārītī specific to the Yunnan region, which has been passed down to this day.

From the perspective of image analysis, there are two main types of images of Hārītī in the Yunnan region. One is represented by the image of Hārītī painted by Zhang Shengwen 張勝溫, a local painter of Dali, in his Sanskrit Image Volume (Fan Xiang Juan 梵像卷). The painting shows Hārītī seated on a throne, holding a child in her left arm, two children playing below the throne, and three maids caring for other children, while breastfeeding, dressing, and holding them. Additionally, three more children are playing in front of the scene (Fig. 11). The image of a nursing maid suckling a child is identical to the statue of Hārītī found in Sichuan 四川. Both the No. 122 Grotto statue in the Dazu rock carvings (Dazu Shike 大足石刻) located at North Hill (Beishan 北山) (Fig. 12) and the No. 9 Grotto statue in the Anyue 安嶽 rock carvings located at Rock Gate Hill (Shimen Shan 石門山) in Sichuan (Fig. 13) were created during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279). In both, Hārītī is centered and sits high above, while bare-breasted maids suckle infants. This suggests that such a form of Hārītī was likely introduced from Sichuan, a province bordering Yunnan. However, these patterns were not prevalent among believers.

Materials: paper. Dimensions: H. 30.4 cm × W. 1635.5 cm. Collection of the Palace Museum in Taipei. Photo source: the official website of the Palace Museum in TaipeiFootnote

Sanskrit Image Volume. https://theme.npm.edu.tw/selection/Article.aspx?sNo=04009134. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

.The other main type is represented by the image of the Dragon Maiden of Blessedness and Merit (Fude Longnü 福德龍女) by Zhang Shengwen in his Sanskrit Image Volume (Fig. 14). The dragon Maiden of Blessedness and Merit is a fusion of Hārītī and the local Yunnan deity White Sister (Bai Jie 白姐) and is also referred to as the Holy Consort White Sister 白姐圣妃 or Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother (Baijie Shengfei Helidimu 白姐聖妃訶利帝母) (Hou, 2012, pp. 357–374). The depiction of Dragon Maiden of Blessedness and Merit in the Sanskrit Image Volume is a queen-like figure, who pats a child on the top of their head with her right hand, places her left hand before her breast and has three dragons on her head as decoration. Her image precisely matches the Holy Consort White Sister described in the Rituals for the Bodhimaṇḍa of the God Mahākāla (Da Hei Tian Shen Dao Chang Yi 大黑天神道場儀). The description of that image reads, “Balancing three dragons on her head, with her arms drooping on either side… placing her left hand on her heart… her right hand on top of a child (Fang, 1998, p. 378).” This written record indicates that the Dragon Maiden of Blessedness and Merit is the Holy Consort White Sister.

Materials: paper. Dimensions: H. 30.4 cm × W. 1635.5 cm. Collection of the Palace Museum in Taipei. Photo source: the official website of the Palace Museum in TaipeiFootnote

Dragon Maiden of blessedness and merit Sanskrit Image Volume. https://theme.npm.edu.tw/selection/Article.aspx?sNo=04009134. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

.The White Sister, the daughter of a senior named Yang Huanxi 楊歡喜 from Xizhou 喜洲, Yunnan, is the result of her aged and childless father’s prayers to the gods. While bathing by the river one day, she encountered a piece of wood transformed by the Dragon King (Long wang 龍王) who impregnated her, and she later gave birth to two children. Then, she gave her children the surname Duan, which means “piece” as in “a piece of wood” (Yang, 1450). After her death, she was conferred the title of the Holy Consort White Sister and has always been worshiped as a fertility goddess in the Yunnan region. Since both Hārītī and White Sister are capable of bestowing offspring, the locals combined the two goddesses’ functions and referred to them collectively as “Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother.” Therefore, it is not difficult to understand that the Hārītī in the Yunnan region is displayed as an image of a queen.

Likewise, the images of children depicted in the Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother should symbolize the Holy Consort White Sister’s and Helidi Mother’s abilities to protect children and bestow offspring. Why did three dragons appear on her head as an ornament? The reason was closely associated with dragon worship in the Yunnan region, and we can find an answer from the Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother statue in Zhemu Temple, Yunnan.

Zhemu Temple 哲母寺, located in Jianchuan 劍川, Yunnan, was completed in the year 1450 during the Ming Dynasty. It continues to attract numerous worshippers and pilgrims even to this day. “Zhemu 哲母” refers to the “Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother” in the dialect of Yunnan. The temple is home to two seated josses, one of which depicts the Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother gently stroking a child’s head. The upper portion of the deity’s head is deteriorated, and the three dragons are missing.

The other deity puts his hands together, and his face is broken (Fig. 15). According to Li Wenhai 李文海, the Zhemu Temple used to be called the “Combined Temple of Holy Consort White Sister and Dragon King,” demonstrating that the two deities are the combined Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother and the Dragon King (Lijiang Local Chronicle Compilation Office, 2021, p, 3). Li Wenhai described the image of Hārītī as follows: “She balances three dragons on top of her head, signifying the three realms. [She is] touching her breast with her left hand…and stroking the child’s head with her right hand.” These features are consistent with the image of the Dragon Maiden of Blessedness in the above Sanskrit Image Volume.

The reason for combining the Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother with the Dragon King was to quell flooding.

Historically, the White Sister Temple was highly efficacious at stopping inundations. People molded an image of the Dragon King next to the White Sister to enhance flood prevention through the combined power of both entities (Zhang, 2010, p. 114).

The Jianchuan Chronicles compiled during the Guangxu 光緒 era also record something similar: “In the Dragon Lord’s Shrine… Inside White Nanda Dragon King is worshiped, and inside is the Helidi Mother. The statue of the Helidi Mother was introduced from the western region and was originally worshiped at White Sister Temple; it was later transferred here to cease inundations (Yang and Zhao, 2007, p. 683).” Moreover, the “Helidi Mother is venerated at White Sister Temple, which is situated five kilometers northeast of the city, to beseech the deities for rain or good weather (Yang and Zhao, 2007, p. 684).” From this account, it can be inferred that Hārītī has the functions of stopping inundations and praying for good weather, be it rain or sunshine. The combination of the Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother and Dragon King or dragon head precisely reflects the beliefs of Hārītī and the dragon in Yunnan.

In light of the above evidence, the belief in Hārītī still exists today, but it is parasitic within localized beliefs. The Hārītī deity introduced into the Yunnan area has combined with the White Sister, the local fertility goddess, into a belief of the “Holy Consort White Sister and Helidi Mother”, which displays an image of a queen receiving widespread acclaim. In addition, she integrated with the local Dragon King belief by incorporating dragon elements into her image or forming a combination with the Dragon King to manifest her new duty of stopping floods.

Hārītī belief continues to be preserved in Yunnan in such a parasitic manner for various reasons. First, the region has a rich history of fertility culture (Yang, 2008, pp. 86–89), and the function of Hārītī in bestowing offspring and safeguarding children precisely meets this desire. Second, Yunnan’s unique geographical location has kept it under the continuous influence of Indian cultures, particularly Buddhism (Che, 2003, pp. 82–86). This geographical advantage has contributed to the spread and preservation of the Hārītī belief system in Yunnan. Furthermore, Yunnan Province has been a multiethnic region since ancient times (Zhao, 2001, 89–92) and has hosted various religions, such as Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, indigenous beliefs, and folk religions. The cultural atmosphere of coexistence and fusion among multiple ethnicities and religions allows beliefs to intermingle and provides a foundation for the assimilation and endurance of the Hārītī faith.

Reasons for the prosperity and melting of Hārītī in China

By analyzing the images of Hārītī above, it is apparent that the images of Hārītī have continued to change in different historical phases, displaying a general trend of continuous localization and assimilation. In other words, this process of image shifting embodies the ascent, primacy and decline of Hārītī in China. Below, we aim to explore the social factors that lead to the transformation of Hārītī’s image and reveal the reasons for the rise and fall of a foreign deity in China.

Prosperity: venerated offspring-bestowing function

From the Western Jin Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty, Hārītī gradually transitioned from the Gandhara style to Sinicization in her image, and her faith prevailed in China. The fundamental reason why she took root in China is her offspring-bestowing and child-protection functions, which meet the needs of Chinese people aspiring for reproduction. The Chinese people, who always value a flourishing population, exhibit endless reverence and expectations for life. Specifically, the social formation of agricultural culture in ancient China required a large workforce to work the land to ensure production and the continued sustenance of the Chinese populace. This philosophy aligns with the adage that “one noncultivating farmer will cause starvation, and one nonweaving woman will lead to cold (Yue, 2015, p. 128).” In other words, the lack of a workforce means difficulty sustaining average production and life for individual families. The massive demand for a workforce in Chinese society objectively reinforces the cultural belief that happiness is attained through having numerous offspring.

Second, since China has been a male-dominated society over time, women are entitled to little to no rights, including the right to property accession. Therefore, lineage continuation not only involves the continuation of patrilineal lines but also determines women’s status in the family and their future status in life. Consequently, Chinese women are as eager as men to have children (Zhou, 2012, p.13–16). Then, Confucian culture, which has long been dominant in China, advocates continuation of the lineage as the core of fulfilling the filial duty to one’s parents. Under the influence of this belief, people strive to have numerous offspring to repay their parents for their birth and upbringing while also safeguarding the realistic interests of their clans. The hope is that future generations will achieve success and bring honor to their families (Du, 2017, p. 11). Commonly heard proverbs among the public, such as “there are three forms of unfilial conduct, of which the worst is to have no descendants,” “the more sons, the more blessings,” and “the mother’s honor increases as her son’s position rises”, exemplify the Chinese yearning for descendants. Thus, the custom of praying for offspring has been prevalent throughout Chinese history. Hārītī has the functions of protecting children and sending children to desiring couples; these functions meet the eager desire to pray for descendants among the Chinese people, and the goddess was therefore incorporated into China’s belief in fertility gods.

From the perspective of historical era, the phase in which the image of Hārītī shifted from Hellenism to Sinicism corresponds to the Tang Dynasty. This period was one of the most prosperous times in Chinese history, featuring a stable social structure, rapid economic growth, and strong demand for population growth. In social prosperity, the total GDP of the Tang Dynasty reached 26.82 billion US dollars, with a GDP per capita of 450 US dollars, accounting for 26.2% of the global economy and securing its position as a world leader (Maddison, 2003, pp. 257–260). Next, viewing demographic changes in China’s past dynasties, the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BC) had a population of approximately 20 million, the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC–24 AD) had approximately 50 million, and the early years of the Tang Dynasty saw a decrease to only approximately 25 million due to continuing wars, but the population rose to 90 million (Xing, 2017, pp. 10–12; Wang, 1995, pp. 46–297) in the late years of this Dynasty. For the first time, the Chinese population reached a new height, representing a landmark in the history of population growth and reflecting a strong demand for increasing offspring among the common people. The introduction of the belief in Hārītī and its Sinicization conformed to the trend of historical development and satisfied the childbearing needs of the people at that time.

It should be emphasized that, during the initial widespread acceptance of Hārītī by the Chinese, there were already various indigenous fertility deities in China. However, Hārītī remained accepted by the Chinese population, alongside other deities associated with fertility. This phenomenon can be attributed to the pragmatism adopted by the Chinese towards deity worship, as they worship them mainly to fulfill their requirements for offspring, irrespective of their religious origins. Therefore, these deities are revered for their effectiveness in granting fertility, irrespective of whether they originate locally or from foreign lands and regardless of their Buddhist or Taoist identity. For instance, during the Tang and Song dynasties, the Buddhist Avalokitesvara and the Taoist Empress of Mount Tai 泰山娘娘, as well as Matsu 媽祖, worshiped in the southern coastal regions as a fertility goddess, were equally worshiped as deities of fertility (Qi and Du, 2009, pp. 128–132). Additionally, as recorded in the County Annals of Wushan (Wushan Xianzhi 巫山縣誌), fertility deities such as the Empress of Mount Tai, Avalokitesvara, and Hārītī were worshiped together in an old hall on the mountaintop (Yuan, 2011, p. 174). Therefore, Hārītī, possessing the powerful function of bestowing offspring, was naturally accepted by the Chinese people.

Additionally, the prevalence of Hārītī faith in China was also encouraged by the strategy of disseminating Buddhism. During its spread, Buddhism solicited worship from those who experienced various forms of human suffering, such as birth and old age, sickness, and death, to attract more believers from the common people. As one of the most urgent appeals from the populace, reproduction was incorporated into the items that Buddhism was most concerned about. From the perspective of the functions of Hārītī, as the first goddess converted to Buddhism, Hārītī was entrusted with the most critical duties of giving birth and child protection and bestowed her powerful fertility broadly on the women of the population. From the perspective of temple precepts, Buddhism elaborated upon the law of feeding hungry ghosts in its Vinaya, which specified that it is the duty of a temple to enshrine Hārītī and protect her children to ensure the continued inheritance of the belief in Hārītī (Li, 2003, p. 259). From the perspective of Buddhist propagation, since its introduction into China, where there was a strong demand for praying for offspring, Buddhism has taken advantage of this opportunity to publicize and promote the offspring-bestowing function of Hārītī widely to attract more attention. For example, scriptures translated into Chinese, such as The Sutra of the Demon-mother told by the Buddha of the Western Jin Dynasty and Hārītī and Beloved Children Accomplishment Ritual (Da Yao Cha Nü Huanxi Mu Bing Aizi Chengjiu Fa大藥叉女歡喜母並愛子成就法) of the Tang Dynasty, substantially underlined her fertility-giving and religious functions of sending offspring and rescuing mothers from birth traumas like shoulder dystocia. Meanwhile, to facilitate better acceptance by Chinese people, Hārītī’s image was gradually Sinicized from the depiction of the goddess in the Gandhara region.

Assimilation: the unacceptable identity of the Yaksha

A review of the image of Hārītī shows that Hārītī worship began to become popular among the common people in the Song Dynasty but also began to decline at the same time. In the many paintings and frescoes themed with raising the alms-bowl, her evil image and yaksha identity are continuously emphasized. The reasons for her decline were many, but the most fundamental was that her duty of protecting childbirth was replaced by the child-giving Avalokitesvara, who was more beautiful and divine.

Therefore, why was Hārītī’s function of protecting the birth of offspring replaced by child-giving Avalokitesvara? For one thing, this function was closely associated with the Chinese people’s negative opinion of Hārītī, whose origin was as a yaksha. Unlike Indians, who sincerely worship yaksha, Chinese people perceived her as an ugly and anthropophagous monster filled with negative and dark powers (Zhan, 2015, p.95). For example, the term ‘female yaksha’ (Mu Ye Cha 母夜叉) is the most vicious analogy for a woman and is used to describe her ugliness and ferocity (Li, 2010, pp.102–104). Before the Song Dynasty, the influence of the yaksha identity on belief in Hārītī was relatively minor. The primary reason for this is related to the initial dissemination of Hārītī worship in China, which initially, occurred through Buddhist scriptures that sought to propagate Buddhism and instill moral values in devotees by emphasizing Hārītī’s positive image and powerful fertility rather than accentuating her repulsive identity as a yaksha. Several Buddhist classics, such as “Hārītī and the Beloved Children Accomplishment Ritual” and the “Hārītī Mantra Sutra (HeLidimu Zhenyan Jing 訶利帝母真言經)”, which were both translated by Amoghavajra, emphasize the causal logic underlying Hārītī’s embrace of Buddhism. They also portrayed her as possessing a striking, respected, and empathetic divine image, in addition to encouraging procreation as one of her religious duties. However, Hārītī’s identity as a yaksha was reinforced in the Song Dynasty. This was related to the propaganda and interpretation of the plot of raising the alms-bowl in the stories relating to her. During the popularization of Hārītī, drama, literary works, and other forms of entertainment culture had significant influences on her reception. Based on the Buddhist classics, artists chose the storyline “Raising the Alms-bowl” to magnify the hostility and competition between a ghost and a deity through artistic and theatrical creations. This created additional interest for audiences, despite the plot being less prominent in the classics. The alterations to the narrative effaced Hārītī’s original religious roles and characteristics, strengthening the negative perception of her as a doomed figure and impacting her image among the general population.

Moreover, since the Tang and Song Dynasties, the object of the Buddhist ceremony of feeding the hungry ghosts has been pacifying various monsters represented by Hārītī, which has undoubtedly reinforced her negative impression among a broad swath of believers. That is, such a so-called goddess is nothing but a humble yaksha or ghost. Therefore, at that time, she was usually called a “bitch (jian ren 賤人)” or “demon mother” (mo mu 魔母). For example, in Script III Conversion of Hārītī, Journey to the West (Xi you ji 西遊記), a poetic drama set to music by Yang Ne 楊訥, she is referred to as a “bitch.”(Wang, 1997, p. 548) In the Southern Song Dynasty, people still had a negative attitude towards her even when worshiping her statue: “Such an evildoer as Hārītī is probably the Guizimu. She used to eat people in the capital before she became a nun. The people had a grudge against her and made this drama. Now that she has become a guardian, she should be eliminated (Pan, 960–1279, p. 25–27).” Obviously, these terms of address and descriptions were all negative enough to show the degree of negative perception among the Chinese people. This negative cognition is the root cause of Hārītī not being absolutely accepted by the Chinese.

Finally, the child-giving aspect of Avalokitesvara was independent of the belief in Avalokitesvara and had become an entirely indigenous Chinese goddess, a better choice as a fertility goddess. Belief in Avalokitesvara was introduced into China when Buddhism entered China. The earliest classic that introduced Avalokitesvara was the Saddharmapundarika Sutra (Zheng Fa Hua Jing 正法華經) by Dharmarasa (Zhu Fahu 竺法護) in the Western Jin Dynasty, which included the description of Avalokitesvara’s supernatural power to bestow offspring (Zhi, 2018, p. 7). However, the belief in Avalokitesvara was not widely popular at that time, so people rarely prayed to Avalokitesvara for descendants (Zhou, 2012, pp. 13–16). During the Sui and Tang dynasties, the belief in Avalokitesvara developed rapidly, and Buddhist propaganda highlighted the efficacy of Avalokitesvara’s ability to bestow offspring; therefore, it became common practice for people to proactively pray for offspring. As a result, numerous statues of child-giving Avalokitesvara appeared, demonstrating that the independent belief in child-giving Avalokitesvara became widespread across a substantial scope of the population (Yu and Jiang, 2012, pp. 13–16). In the Song Dynasty, people focused more on the realistic welfare brought about by religious beliefs (Sun, 1996, p. 369), which resulted in widespread belief in the child-giving Avalokitesvara, who is closely related to their daily lives. Moreover, the belief in the child-giving Avalokitesvara became a folk belief that was firmly rooted at the grassroots level through its constant integration into mundane life.

The “Yi-jian-zhi 夷堅志” by Hong Mai 洪迈 in the Southern Song Dynasty is a collection of realistic novels reflecting the beliefs and lives of urban people. This chapter documents various miraculous stories of Avalokitesvara bestowing offspring. For example, a novel named Zhaiji Sires a Boy (Zhai Ji Dezi 翟楫得子) in Volume 17 records that “at the age of fifty, Zhaiji was childless. Therefore, he painted a picture of Avalokitesvara, to whom he earnestly prayed for offspring, which resulted in his wife’s pregnancy (Hong, 1981, p. 325).” Another similar account is found in the “Mingxiangji” as follows: “Bian Yuezhi… remained childless at the age of fifty. His wife sought a concubine in the hopes of producing a male heir, but the concubine was unable to conceive for several years after entering into concubinage. To pray for the birth of an heir, Bian pledged to recite the Avalokitesvara sutras a thousand times… Eventually, the concubine became pregnant and gave birth to a son (Li, 1990, pp. 531–546).” This reveals the perceived effectiveness of Avalokitesvara in providing offspring for the Song population. Furthermore, there were numerous cliff carvings during the Song Dynasty that depicted Avalokitesvara granting offspring, such as the New Miaozi Cliff Carving in Anyue 安岳 County, Ziyang 资阳 City, Sichuan Province (National Heritage Board, 2009, p. 509); the Foer Yan Valley Cliff Carving in Pengshan 彭山 County, Meishan 眉山 City, Sichuan Province (National Heritage Board, 2009, p. 622); and the Lingyan Temple Cliff Carving in Dazu County, Chongqing Municipality (National Heritage Board, 2010, p. 306). All of these cliff carvings exemplify the assimilation and rise of the belief in Avalokitesvara as a fertility goddess in Song Dynasty society. Ultimately, the localized identity and prominent offspring-sending function of Avalokitesvara enabled her to effortlessly replace Hārītī as the most popular fertility goddess.

Notably, the belief in Hārītī has faded gradually from the visual field, but it has not disappeared completely. She remains in temple statues as one of the Twenty-four Celestial Gods. However, her reproductive function has gradually been forgotten, and she continues only to guard the Buddha dharma and protect all life as an ordinary goddess. Even more obscurely, Hārītī has integrated into local beliefs in regions such as Yunnan to survive parasitically.

Conclusion

Hārītī, as the first fertility goddess in charge of child giving in the history of Buddhism, underwent reforms to her image by localization and an abandonment of her worship arising from demonization after her introduction into China. This reflects the Sinicisation of Buddhism, the development of worship and god-making practices among common people, and shifts in people’s psychological perceptions in religious belief. Initially, Hārītī was the awe-inspiring smallpox goddesses of the region of Gandhara. Later, she was incorporated into the Buddhist system as a yaksha, becoming a fertility goddess who protected pregnant women and children. Her image was influenced by Buddhist art from the Gandhara region, adopting a graceful image of a Greek goddess, which endured when first introduced to China. From the Western Jin Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty, Hārītī worship started to prevail in China. Her image was gradually Sinicized by evolving into a Chinese woman’s image so that the Chinese could better accept her. She wore a Chinese-style bun, a Chinese-style long dress, and Chinese-style embroidered shoes and sat on a Chinese-style seat. In the Song Dynasty, the belief in Hārītī began to prevail widely among people. However, she changed from a noble child-giving and caregiving goddess to a ghost from hell, who was the subject of ridicule for entertainment and amusement, and her duty as a fertility goddess was replaced by Avalokitesvara, who had a higher affinity with the local population. From then on, Hārītī worship declined gradually. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the image of Hārītī was so severely corrupted that a single deity even evolved into three. No longer caring about the source and duties of Hārītī, people worshiped her as a symbolic Buddhist goddess. Her image faded from the visual field in China after the Ming and Qing dynasties. However, she did not disappear. In present-day China, particularly in Yunnan and other regions, she has integrated deeply with the local fertility goddess and survived, parasitically existing within the imagery of other beliefs. It is thus clear that Hārītī underwent an evolution of localization, secularization, demonization, and regionalization in China so that her image is sometimes a goddess and sometimes a ghost, sometimes virtuous and sometimes evil. She is a spirit that has collided with the demands for beliefs among the common people of different periods and regions.

By interpreting the spread of Hārītī in China, we can see how a foreign deity has undergone localization, filtration and recreation through indigenous culture. Hārītī has integrated with the beliefs in fertility goddesses, drama and regional cultures in China to varying degrees throughout various periods and regions, reflecting the localized characteristics of Buddhism during its dissemination in China. Moreover, the acceptance and subsequent adaptation of Hārītī in China reflected the pragmatic attitude towards religious beliefs among the population. The Chinese initially accepted Hārītī due to her offspring-bestowing function. Afterward, her worship declined radically because her identity as a yaksha was accentuated, and she underwent reformation to survive in popular worship following people’s realistic needs. In other words, the choice, acceptance, and even alteration of a specific deity among people demonstrated the inward expectations of the general public at that time, as well as the cultural endorsement and advocacy of the era. The study of the evolution of the image of Hārītī and her worship in China provides a vivid case for research on the rise and fall of foreign deities in China. Hārītī worship offers a new perspective for exploring folk practices and the psychology of deity creation, which deepens the psychological study of popular religion.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analyzed.

Notes

For the sake of convenient expression, this paper mainly uses the translation of “Hārītī”, which generally has no special meaning.

Teaching Buddha, Gandhara. https://bampfa.org/divine-women-slideshow. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

The Buddha at the Great Miracle. https://www.guimet.fr/collections/afghanistan-pakistan/le-buddha-au-grand-miracle. Accessed on 2 August 2023.

The Buddhist Goddess Hārītī with Children. https://collections.lacma.org/node/239439. Accessed on 2 August 2023.

Tempera painting of Hārītī. http://blog.chughtaimuseum.com/?p=2824. Accessed on 2 August 2023.

Twenty-eight Mansions are twenty-eight regions divided by ancient Chinese astronomers to observe the movements of the sun, moon and five stars, which are used to explain the position of the sun, moon and five stars. It is widely used in ancient astronomy, religion, literature and horoscopes, astrology, fengshui, auspiciousness and so on.

Jiebo tu揭缽圖. https://www.dpm.org.cn/collection/paint/228774. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

Statue of Hārītī in Shanhua Temple. https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-cn/File:Statue_of_Hariti_(%E9%AC%BC%E5%AD%90%E6%AF%8D_Guizimu)_in_Shanhua_Temple_(%E5%96%84%E5%8C%96%E5%AF%BA_Sh%C3%A0nh%C3%B9as%C3%AC)_in_Datong,_Shanxi_Province,_China.jpg. Accessed on 8 December 2023.

Sanskrit Image Volume. https://theme.npm.edu.tw/selection/Article.aspx?sNo=04009134. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

Dragon Maiden of blessedness and merit Sanskrit Image Volume. https://theme.npm.edu.tw/selection/Article.aspx?sNo=04009134. Accessed on 3 August 2023.

References

Anonymous (1412–1417) Fo Shuo Gui Zi Mu Jing 佛說鬼子母經 (The Sutra of the Demon-mother told by the Buddha). Nan Jing Li Bu Ci Ji Qing Li Si 南京禮部祠祭清吏司, Nanjing, China

Anonymous (1645–1911) Tuo Luo Ni Za Ji 陀羅尼雜集 (Miscellaneous Dhāraṇīs Collection). Huangbershan Treasure Courtyard Tieyandaoguang master engraving 黃檗山寶藏院鐵眼道光禪師募刻, Kyoto, Japan

Art Research Academy of Shandong Arts College (2020) Yi Shu Xue Lun Cong 藝術學論叢 (Series on Art). Shandong Pictorial Publishing House 山東畫報出版社, Jinan, China

Bazhou District Cultural Relics Management Office (2008) Ba Zhong Shi Ku: Tang Dai Cai Diao Yi Shu巴中石窟: 唐代彩雕藝術 (Bazhong Grottoes: the art of color carving in the Tang Dynasty). Zhejiang Photographic Press 浙江攝影出版社, Hangzhou, China

Che W (2003) Di Li Huan Jing Yu Wen Hua Sheng Cheng —— Yun Nan Shao Shu Min Zu Sheng Yu Wen Hua Xing Cheng Yu Bian Qian De Di Li Xue Jie Shi 地理环境与文化生成——云南少数民族生育文化形成与变迁的地理学解释 (Geographic environment and culture forming–a geographical explanation of the formation and change of fertility culture of ethnic minorities in Yunnan). Popul Res 人口研究 27(6):82–86. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6087.2003.06.018

Cohen RS (1998) Nāga, yakṣiṇī, Buddha: local deities and local Buddhism at Ajanta. Hist Relig 37(4):360–400

Doré H (1920) Researches into Chinese superstitions, vol. 6. Túsewei Printing Press, Shanghai, China

Du Y (2017) Cong Gui Zi Mu Dao Song Zi Guan Yin De Tu Xiang Xue Yan Bian 從鬼子母到送子觀音的圖像學演變 (The image evolution from the Guizimu to the Songzi Guanyin). Chin Tradit Cult 國學 10(1):186–194

Du Y (2017) Song Zi Guan Yin Yan Jiu送子觀音研究 (Study on Songzi Guanyin). Dissertation, Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences

Ebrey P (2004) Nei Wei: Song Dai De Hun Yin He Fu Nü Sheng Huo 內闱: 宋代的婚姻和婦女生活 (Inner quarters: marriage and the lives of Chinese women in the Sung Period). Jiangsu People’s Publishing House 江蘇人民出版社, Jiangsu, China

Fa Y (1935) Fan Yi Ming Yi Ji Yi Jian 翻譯名義集易檢 (Glossary of Buddhist Terms Translation). Shanghai Buddhism Book Bureau上海佛學書局, Shanghai, China

Fang G (1998) Zang Wai Fo Jiao Wen Xian Di 6 Ji 藏外佛教文獻 第6輯 (The sixth part of Buddhist literature outside Xizang). Religious and Cultural Publishing House 宗教文化出版社, Beijing, China

Fang X (1974) Jin Shu 晉書 (Book of the Jin Dynasties). Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, Beijing, China

Foucher A (2008) Fo Jiao Yi Shu De Zao Qi Jie Duan 佛教藝術的早期階段 (The Beginnings of Buddhist Art). Gansu People’s Publishing House 甘肅人民出版社, Lanzhou, China

Getty A (1914) The Gods of Northern Buddhism. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

Guo X, Li S (1999) Da Zu Shi Ke Diao Su Quan Ji Si Nan Shan Shi Men Shan Shi Zhuan Shan Deng Shi Ku Juan 大足石刻雕塑全集 4 南山、石門山、石篆山等石窟 (Complete collection of Dazu rock carvings sculptures vol. 4: Southern Mountain, Shimen Mountain, Shizhuan Mountain and Others). Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House 重慶出版社, Chongqing, China

Hong M (1981) Yi Jian Zhi 夷堅誌 (Firm-and-Even’s Records). Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, Beijing, China

Hou C (2012) Cong Fu De Long Nü Dao Bai Jie A Mei: Ji Xiang Tian Zai Yun Nan De Yan Bian 從福德龍女到白姐阿妹:吉祥天在雲南的演變 (From Dragon Maiden of Blessedness and Merit to White Sister: the Evolution of Sri-maha-devi in Yunnan). Essays Ethn Cult Dali 大理民族文化研究論叢 9(0):357–374

Hou H (2022) Shui Lu Fa Hui De Fa Zhan Yu Yan Bian Kao 水陸法會的發展與演變考 (Research on the development and evolution of the water-and-land services). Voice Dharma 法音 42(6):60–65. https://doi.org/10.16805/j.cnki.11-1671/b.2022.0131

Hsieh M (2009) Gui Zi Mu Zai Zhong Guo —— Cong Kao Gu Zi Liao Tan Suo Qi Tu Xiang De Qi Yuan Yu Bian Qian 鬼子母在中國——從考古資料探索其圖像的起源與變遷 (A study of the origin and development of the representation of Hariti in the Chinese tradition). Taida J Art Hist. Natl Taiwan Univ 臺灣大學藝術史研究所 27(2):107–156. https://doi.org/10.6541/TJAH.2009.09.27.02

Hsuan H (2009) Miao Fa Lian Hua Jing Qian Shi 妙法蓮華經淺釋 (Explanation of the lotus sutra). Religious and Cultural Publishing House 宗教文化出版社, Beijing, China

Huang H (2006) Yuan Ming Qing Shui Lu Hua Qian Shuo 元明清水陸畫淺說 (On the water-and-land paintings of Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties). Buddh Cult 佛教文化 18(2):102–122

Huang R (2005) Bian Jing Can Meng 汴京殘夢 (Decrepit dream of Bianjing). New Star Press 新星出版社, Beijing, China

Kanaoka S (1985) Hārītī God Faith. Xiongshan Court, Tokyo, Japan

Kang D (1998) Pi Lu Si Bi Hua 毗盧寺壁畫 (Murals of Pilu Temple). Hebei Fine Art Press 河北美術出版社, Shijiazhuang, China

Khan M (1997) Jian Tuo Luo Yi Shu 犍陀羅藝術 (Gandhara art). Commercial Press 商務印書館, Beijing, China

Li F (1990) Tai Ping Guang Ji Juan 100、Juan 101 太平廣記卷100、卷101 (Extensive records of the Taiping era Volume 100, Volume 101). Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House 上海書店出版社, Shanghai, China

Li L (2002) Xi You Ji Gui Zi Mu Yu Jiu Zi Mu《西遊記》、鬼子母與九子母 (Journey to the West, Hārītī and Nine-son Mother). Chin Class Cult 中國典籍與文化 11(4):33–40. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-3241.2002.04.006

Li L (2016) Bu Kong Suo Yi He Li Di Mi Dian Ji Tu Xiang De Yan Jiu 不空所譯訶利帝密典及圖像的研究 (Hārītī Tantras Translated by Amoghavajra and Hārītī Icons). J Natl Mus China 中國國家博物館館刊 38(1):82–96

Li L (2017) Shui Lu Hua Zhong De Gui Zi Mu Tu Xiang 水陸畫中的鬼子母圖像 (The image of the Guizimu in the water-and-land paintings). Turfanological Res 吐魯番學研究 10(2):82–98+159. https://doi.org/10.14087/j.cnki.65-1268/k.2017.02.010

Li L (2018) Gui Zi Mu Yan Jiu Jing Dian Tu Xiang Yu Li Shi 鬼子母研究: 經典、圖像與歷史 (Research on Guizimu: classics, images and history). Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House 上海書店出版社, Shanghai, China

Li R (ed) (2006) Za Bao Zang Jing 雜寶藏經 (Samyuktaratnapitaka-sutra). Unity Press 團結出版社, Beijing, China

Li X (2003) Dun Huang Mi Jiao Wen Xian Lun Gao 敦煌密教文獻論稿 (Discussion on Dunhuang esoteric manuscripts). People’s Literature Press 人民文學出版社, Beijing, China

Li X (2010) ”Ye Cha” Yi Ci Zai Han Yu Zhong De Yan Bian “夜叉”一詞在漢語中的演變 (The Evolution of the Word “Yaksha” in Chinese). Root Explor 尋根 17(5):102–104

Li Y (2019) Bao Ning Si Ming Dai Shui Lu Hua De Xian Miao Te Dian 寶寧寺明代水陸畫的線描特點 (Line drawing characteristics of water-and-land paintings in Baoning Temple in Ming Dynasty). Art Res 藝術研究 22(2):66–67. https://doi.org/10.13944/j.cnki.ysyj.2019.0116

Lijiang Local Chronicle Compilation Office (2021) Li Jun Shi Zheng Li Jun Wen Zheng 麗郡詩徵 麗郡文徵 (Lijun Shizheng Lijun Wenzheng). Yunnan Nation Publishing House 雲南民族出版社, Kunming, China

Liu M (1996) Qiu Ci Ku Mu Tu La Fa Xian De Gui Zi Mu Bi Hua 龜茲庫木吐拉發現的鬼子母壁畫 (The Fresco of Hārītī discovered at Qiuci Kumtula Grottoes). Hist Geogr Rev Northwest China 西北史地 17(1):37–38

Liu Q (2023) Bao Ning Si Shui Lu Hua Tu Xiang Xin Tan 寶寧寺水陸畫圖像新探 (A new probe into the Image of water-and-land paintings in Baoning Temple). N. Arts 新美術 44(2):100–125

Liu X, Yang X (2014) Fan Xiang Yi Zhen Si Chuan Ming Dai Fo Si Bi Hua 梵相遺珍 四川明代佛寺壁畫 (Murals of Buddhist temples in Sichuan during the Ming Dynasty). People’s Fine Arts Publishing House人民美術出版社, Beijing, China

Long H (2003) Da Zu Shi Ke Zhong De Ming Su Huang Hou、He Li Di Mu、Jiu Zi Mu Yu Song Zi Guan Yin 大足石刻中的明肅皇後、訶利帝母、九子母與送子觀音 (Empress of Ming Su in Dazu Rock Carvings, Helidi Mother, Nine-son Mother and child-giving Avalokitesvara). J Chin Cult 中華文化論壇 10(1):137–142. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-0139.2003.01.031

Ma J (2004) Pu Xian Xi Yu Song Yuan Nan Xi、Ming Qing Chuan Qi 莆仙戲與宋元南戲、明清傳奇 (Puxian Opera, Southern Opera of Song and Yuan dynasties, Legend of Ming and Qing dynasties). China Theatre Press 中國戲劇出版社, Beijing, China

Maddison A (2003) Shi Jie Jing Ji Qian Nian Shi 世界經濟千年史 (Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run). Peking University Press 北京大學出版社, Beijing, China

Madhurika KM (2009) From Ogress to Goddess, Hariti: a Buddhist deity. IIRNS Publications Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India

Meng Q (1957) Ben Shi Shi 本事詩 (Benshi poetry). Classical Literature Publishing House 古典文學出版社, Beijing, China

Murray JK (1981) Representations of Hāritī, the Mother of Demons, and the Theme of “Raising the Alms-Bowl” in Chinese Painting. Artibus Asiae 43(4):253–284

National Heritage Board (2009) Zhong Guo Wen Wu Di Tu Ji Si Chuan Fen Ce 中國文物地圖集四川分冊 (Sichuan branch of the atlas of Chinese cultural relics). Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社, Beijing, China

National Heritage Board (2010) Zhong Guo Wen Wu Di Tu Ji Chong Qing Fen Ce 中國文物地圖集重慶分冊 (Chongqing branch of the atlas of Chinese cultural relics). Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社, Beijing, China

Niu Z (2015) Lun Liao Jin Si Yuan Cai Su De Shi Dai Te Zheng —— Yi Da Tong Shan Hua Si Da Xiong Bao Dian Nei Er Shi Si Zhu Tian Wei Li 論遼金寺院彩塑的時代特徵——以大同善化寺大雄寶殿內二十四諸天為例 (Liao and Jin dynasty temple colored sculptures: an analysis of temporal characteristics—a case study of the twenty-four celestial gods in the main hall of Shanhua Temple in Datong). Pop Lit Art 大眾文藝 60(12):83–84. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-5828.2015.12.069

Pan Z (960-1279) Fo Zu Tong Ji 佛祖統紀 (Buddha discipline). https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/T2035_033. Accessed 10 Aug 2023

Qi Y, Du W (2009) Lun Tang Song Shi Qi De Sheng Yu Shen Xin Yang Ji Qi Te Dian 論唐宋時期的生育神信仰及其特點 (Study on belief and features of birth-goddess in Tang dynasty and Song dynasty). Ningxia Soc Sci 寧夏社會科學 28(2):128–132

Schopen G, Gomez LO (eds) (2014) Buddhist Nuns, monks, and other worldly matters: recent papers on monastic Buddhism in India. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, pp 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824873929

Shanxi Museum (2015) Bao Ning Si Ming Dai Shui Lu Hua Di Er Ban 寶寧寺明代水陸畫 第2版 (Ming Dynasty water-and-land paintings in Baoning Temple Second edition). Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社, Beijing, China

Shi Y (1412) Gen Ben Shuo Yi Qie You Bu Pi Nai Ye Za Shi 根本說一切有部毗奈耶雜事 (Mūlasarvāstivādah-vinaya-sudraka-vastu). Sutra Collection Academy 藏經書院, Kyoto, Japan, 1417

Soper AC (1960) A vacation glimpse of the T’ang temples of Ch’ang-an. The Ssu-t’a Chi by Tuan Ch’eng-shih. Artibus Asiae 23(1):15–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/3248027

Su B (1996) Zhong Guo Shi Ku Si Yan Jiu 中國石窟寺研究 (Research on Grotto Temples in China). Cultural Relics Press文物出版社, Beijing, China

Sun C (1996) Zhong Guo Wen Xue Zhong De Wei Mo Yu Guan Yin 中國文學中的維摩與觀音 (Vimo and Avalokitesvara in Chinese Literature). Higher Education Press高等教育出版社, Beijing, China

Sun Y, He P (2019) Tu Shuo Jian Tuo Luo Wen Ming圖說犍陀羅文明(Gandhara Civilization in Picture). Joint Publishing生活·讀書·新知三聯書店, Beijing, China

Wang S (1997) Zhong Guo Ju Mu Ci Dian 中國劇目辭典 (Dictionary of Chinese Repertoire). Hebei Education Publishing House 河北教育出版社, Shijiazhuang, China

Wang Y (1956) Ming Xiang Ji 冥祥記 (Ming Xiang Ji). Literary Ancient Books Publishing House 文學古籍刊行社, Beijing, China, Beijing

Wang Y (1995) Zhong Guo Ren Kou Shi中國人口史(Chinese population history). Jiangsu People’s Publishing House江蘇人民出版社, Nanjing, China

Wen Y (1985) Tian Wen Shu Zheng 天問疏證 (The explanation of Tian Wen). Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House 上海古籍出版社, Shanghai, China

Xia G, Bao J (2017) Han Chuan Fo Jiao Zhong De Gui Zi Mu Xing Xiang Yan Bian Kao Shu 漢傳佛教中的鬼子母形象衍變考述 (Research on the evolution of the image of Hāritī in Chinese Buddhism). J Lanzhou Univ (Soc Sci) 蘭州大學學報 45(5):52–58

Xiang Y (2005) Jiu Zi Mu · Gui Zi Mu · Song Zi Guan Yin —— Cong “San Yan Er Pai” Kan Zhong Guo Min Jian Zong Jiao Xin Yang De Fo Dao Hun He 九子母·鬼子母·送子觀音——從“三言二拍”看中國民間宗教信仰的佛道混合 (Jiuzimu Guizimu Songzi Guanyin–The mixture of Buddhism and Taoism in Chinese Folk religious beliefs from the Perspective of “San Yan Erpai”). J Ming-Qing Fiction Stud 明清小說研究 21(2):171–181. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-3330.2005.02.018

Xing R (2017) Zhong Guo Li Shi Shang De Ren Kou Zeng Zhang、Qian Yi Yu Wen Ti 中國歷史上的人口增長、遷移與問題 (Population growth, migration and problems in Chinese history). Teach Exam 教學考試 7(8):10–12

Xu Q (2017) Shui Lu Fa Hui Yu Shui Lu Hua Qian Yi 水陸法會與水陸畫淺議 (A brief discussion on the water-and-land services and water-and-land paintings). Appreciation藝術品鑒 7(2):250

Yang A (1450) San Ling Miao Ji 三靈廟記 (The Story of Sanling Temple). Sanling Temple, Dali

Yang G(2008) Yun Nan Shao Shu Min Zu Chuan Tong Sheng Yu Wen Hua 雲南少數民族傳統生育文化 (Birth Culture in Yunnan Minority Tradition). J South-Central Univ Nationalities (Humanit Soc Sci) 中南民族大學學報(人文社會科學版) 28(6):86–89. https://doi.org/10.19898/j.cnki.42-1704/c.2008.06.016

Yang J (2012) Cong Bi Hua Zheng Ju Kan Gui Zi Mu Zai Gu Dai Zhong Guo De Yan Bian 從壁畫證據看鬼子母在古代中國的演變 (On the evolution of the Guizimu in Ancient China from the evidence of murals). J Suzhou Art Des Technol Inst 蘇州工藝美術職業技術學院學報 10(4):39–42. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-3848.2012.04.011

Yang S, Zhao Y (2007) Da Li Cong Shu Fang Zhi Pian Juan 9 大理叢書 方誌篇 卷9 (Local Chronicles of Dali Series of Books, vol. 9). National publishing house民族出版社, Beijing, China

Yu T, Jiang X (2012) Song Zi Guan Yin Xin Yang De Qi Yuan He Chu Bu Fa Zhan 送子觀音信仰的起源和初步發展 (The origin and preliminary development of the Songzi Guanyin Belief). J Leshan Teach Coll 樂山師範學院學報 27(3):110–112. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-8666.2012.03.028

Yuan Q (2011) Praying for heirs: the diffusion and transformation of Hāritī in East and Southeast Asia. 중국사연구: 117–205

Yuan Q (2017) Mo Shen Zhi Bian: Gui Zi Mu Xin Yang Zai Zhong Guo He Dong Ya Di Qu De Chuan Bo Yu Bian Rong 魔神之變:鬼子母信仰在中國和東亞地區的傳播與變容 (The change of the Devil God: the diffusion and transformation of Hārītī in China and East Asia). Ancient Books Publishing House 上海古籍出版社, Shanghai, China

Yuan Z (2011) Da Tong Shan Hua Si Er Shi Si Zhu Tian Xiang Kao Bian 大同善化寺二十四諸天像考辨 (A critical examination of the twenty-four celestial gods statues at Datong Shanhua Temple). Studies in World Religions 世界宗教研究 33(4):31–47. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-4289.2011.04.005

Yue A (2015) Guo Xue Yu Ke Xue 國學與科學 (Chinese Studies and Science). Capital University of Economics and Business Press 首都經濟貿易大學出版社, Beijing, China

Yue S (2007) Tai Ping Huan Yu Ji 太平環宇記 (Universal Geography of the Taiping Era). Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, Beijing, China

Yungang Grottoes Cultural relics Preservation Office (1994) Zhong Guo Shi Ku Yun Gang Shi Ku 2 中國石窟 雲岡石窟 2 (China Grottoes Yungang Grottoes 2). Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社, Beijing, China

Zhan Y (2015) “Long” Yu “Ye Cha” Xing Xiang Zai Zhong Guo De Jie Shou “龍”與“夜叉”形象在中國的接受 (Reception of “Dragon” and “Yaksha” Images in China). Chi Zi 赤子 15(18):95