The Life and Times of the Kung Fu Film

The Kung Fu film descends from legends, and its history has mirrored the fate of its homeland. Here’s what every fan needs to know.

Kung Fu is, naturally, the beating heart of its eponymous film genre, but how did we go from ancient martial art to blockbuster movies? In this guide, we’ll cover the rise of the Kung Fu films and what aspiring filmmakers need to know to get started in the genre.

For starters, we should probably stop calling the Kung Fu film a “genre.” Technically speaking, it’s a sub-genre of the martial arts film, which also includes Wuxia, karate films, and action-comedy films. (Related movies include gun-fu, jidaigeki, and chambara, or samurai films.)

This parent genre is pretty straightforward—as you might expect, its primary element is combat. The fight choreography is what the genre’s fans show up for; however, the martial arts film is more than a bunch of warriors wailing on each other for 80 minutes.

Combat, in the martial arts film (and, importantly for us, in the Kung Fu film), is storytelling. Training sequences, instruction, rivalries, heroism, sacrifice, and loss are all narrative tools that we don’t always see in other film genres. These aren’t necessarily new tools—we’ve been telling combat narratives for as long as we’ve been beating on each other. However, these tools have taken on different uses and meanings in various martial arts contexts.

There’s plenty else in the martial arts film to keep butts in seats. Action sequences, hand-to-hand combat, gun fights, and stunt work keep us riveted as each scene outdoes the one before it. As it emerged, however, the Kung Fu film evidenced a new palate for martial arts cinema—one that would differentiate it from its predecessor, the Wuxia film.

Interestingly, the development of the Kung Fu film has remained inexorably tied to the finances and politics of its homeland—Hong Kong—in ways that other film sub-genres haven’t been.

Let’s take a look.

How Did We Get Here?

Before we got the Kung Fu film, we watched Wuxia films. Wuxia literally means “martial heroes.” It’s a genre of Chinese fiction that’s rooted in elements of fantasy and the supernatural. The heroes of Wuxia fiction, the xiákè, are wandering heroes similar to the ancient chivalric knights-errant, the Japanese ronin, and the modern Western film hero. The xiákè are honor-bound to stand up against injustice wherever they find it, especially among the common man, from whose social class they typically hail.

Wuxia films typically relied on cheap special effects, animation, and fantasy cliches to tell their stories. You know the type—gods, demons, and things flying everywhere. Shenguai Wuxia literally means “gods and demons” Wuxia. This niche fantasy found popularity in newspaper serials in the 1950s and then claimed the silver screen in the 1960s.

Enter Bruce Lee

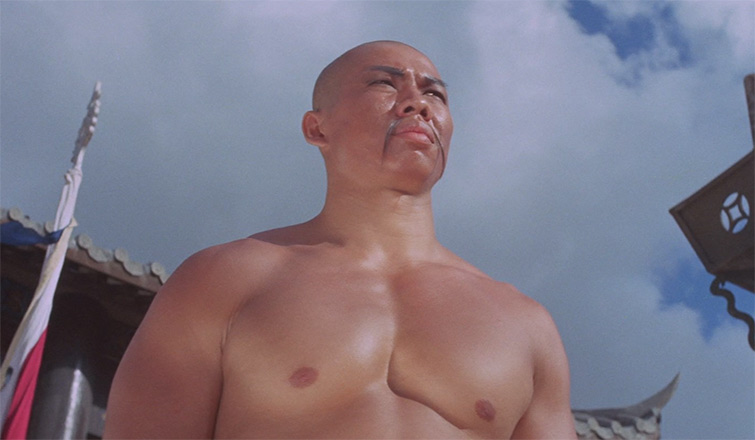

In the 1970s, Hong Kong was enjoying an economic boom, and Kung Fu films began to displace the Wuxia film—fights were choreographed more realistically, and fantasy elements were discarded for grittier, real-world conflicts between good and evil.

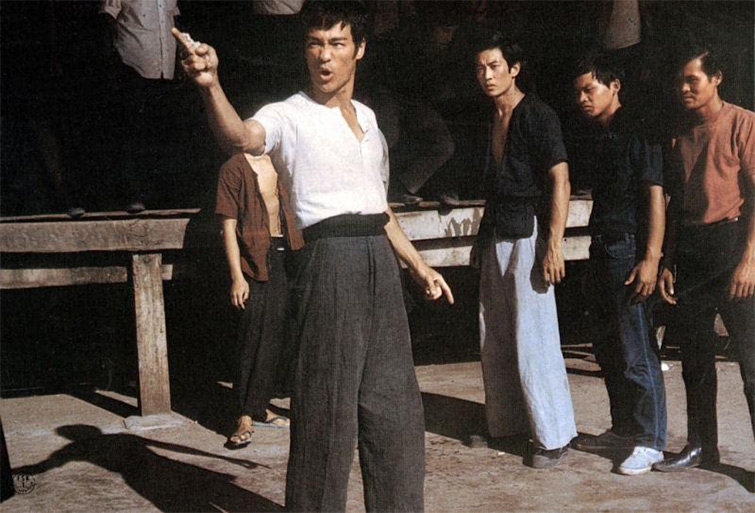

When Bruce Lee’s first Kung Fu film, The Big Boss, came out in 1971, Kung Fu became big business, and the film went on to enjoy international success—and begin the Kung Fu craze that would sweep the world. (Indeed, Lee is largely responsible for casting actual martial artists.) The Kung Fu film found particular traction among marginalized groups in South Asia, African Americans, and Asian Americans, for whom the sub-genre’s emphasis on speaking truth to imperialist power struck a nerve.

Bruce Lee wasn’t alone, however, as the folks at TV Tropes have pointed out:

The boom in popularity throughout the 70s and 80s internationally also lead to numerous films elevating the careers of Asian action stars such as Jackie Chan, Jet Li and Donnie Yen, but also other action stars from different countries that notably include Jean-Claude Van Damme, Steven Seagal, Sonny Chiba and Chuck Norris.

Did Someone Say Jackie Chan?

Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung brought their experiences as stunt men with the Peking Opera to the Kung Fu comedy. As students of the China Drama Academy, both actors had experience with combat and dance.

Besides the obvious slapstick laughs and general hi-jinx, the martial arts in Kung Fu comedies were decidedly more fluid and acrobatic than in traditional Kung Fu films. It’s not hard to imagine why. Switching from a pie in the face to a hardcore Kung Fu fistfight (and back, and back, over and over . . .) would be enough to make you dizzy. The moods just don’t match. The Kung Fu comedy needed combat that could take a joke.

As meteoric as this rise in sub-generic popularity was, its decline would be similarly cataclysmic. Bruce Lee died unexpectedly just two years later in 1973, and a stock market crash threw Hong Kong into an economic recession. Just as the Kung Fu film had ridden Hong Kong’s economic good times to the top of the charts, it now fell with them (and the sub-genre’s iconic superstar) in favor of a new kind of Kung Fu film that would appeal to those suffering from the recession—the Kung Fu comedy.

Hong Kong audiences were hungry for comedies and satires to brighten the mood, so with a bit of Cantonese satire on its back, the Kung Fu film parted the curtain, and Jackie Chan took center stage in 1978.

Kung Fu Films Today

But the story of the Kung Fu film doesn’t end with the sound of belly laughs. In the ’90s, martial arts film fans started to get antsy about the handoff of Hong Kong back to Chinese control in 1997. Would the new communist government allow the filmmaking freedom everyone was accustomed to?

No one was quite certain, and other players in the martial arts film scene decided to start making moves. South Korea, Japan, Thailand—seemingly everyone started producing martial arts films in the hopes of filling the feared communist void.

But in the end, it was all just a lot of sturm und drang. Arty martial arts films germinated in Hong Kong all on their own, with titles like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Hero, and House of Flying Daggers. China still produces many martial arts film, and, somewhat cyclically, CG animation is bringing animation and non-martial artists back into the game.

Plus ça change.

How to Make Your Own Kung Fu Film

Let’s be honest: it’s going to be tough to make a Kung Fu film if you don’t have any Kung Fu. But, since when have the details ever stopped us? It wouldn’t be a proper PremiumBeat write-up if we didn’t at least suggest a few ways you can get out there and get to work on your movie.

Let’s start with this classic tutorial.

And here are a few of our favorite posts from the PremiumBeat archive.

- 6 Tutorials for Filming Realistic Fight Scenes

- Filmmaking Tips: The Ins and Outs of Fight Scene Choreography

- Production Tip: How to Edit a Fight Scene for Rhythm and Pacing

- Directing Fight Cinematography: The Right Way and the Wrong Way

Lastly, don’t forget you’ll need a slammin’ playlist to sell your martial arts movie. We humbly suggest this one.

Cover image via Warner Bros.

For more information on various film genres—check out the articles below!