The history of paan: an Indian treat made with a betel leaf that’s recommended in the Kama Sutra and praised by Ayurveda practitioners

- Known by different names in various Indian languages, millions of Indians chew paan every day and have done so for thousands of years

- Used as a mouth freshener or a post-meal treat, it is also touted as an aphrodisiac and is praised by Ayurveda practitioners for its health-giving properties

Paan is everywhere in India. The treat – a betel leaf stuffed with a variety of ingredients – can be found in people’s homes, at restaurants, shopping centres and markets.

The kiosk of the street corner paanwallah (seller of paan), where people gather over gossip and gilauri (prepared paan triangles), is like a modern-day coffee shop. Usually a flimsy, colourful structure with a tarpaulin roof, it sports a wooden table and steel containers filled with paan condiments. Sachets of chewing gum and mouth fresheners hang over it like party decorations.

The moment an order is placed, the vendor’s hands start flying over his accoutrements – the heart-shaped, emerald-hued paan (the word refers to both the leaf, and the preparation made with it) is pulled out from under a wet muslin cloth, smeared with slaked lime and the astringent, chocolate-brown herb kattha.

Tambul, tamalapaku, nagavalli, nagarbel, vettile … known by different names in different Indian languages, the herby paan is deeply rooted in the subcontinental culture. Millions of Indians chew paan daily – its piquant and peppery taste make it an excellent mouth freshener or a post-meal treat.

Ancient texts mention how the betel leaf’s different parts represent different Hindu deities: Lakshmi in front, Shiva around the edges, and Yama – the Lord of Death – residing in the stalk, the unfavourable part, to be shunned.

Paan is gifted during weddings to guests, or to teachers to seek blessings. It’s also used prolifically in traditional medicine. Priests receive a betel nut and a coin placed on the leaf as a mark of respect. In India’s northeastern state of Assam, paan and betel nuts are offered to guests with invitation cards for marriage. In West Bengal, brides enter the marriage venue covering their faces with betel leaves.

History of chicken tikka masala: loved in Britain, ignored in India

The ancient Hindu compendium of religious texts, Skanda Purana, which dates back to the sixth century, has references to paan.

“In the story of Samudra Manthan, the churning of the ocean by Gods and Demons in search of Amrit, the nectar of immortality, the betel leaf was one of the many celestial objects that was discovered. The holy leaf also finds mentions in epics like Mahabharata, the Bhagavata Purana and the Vishnu Purana, which is how it acquired primacy in religious ceremonies,” explains scholar and priest Ram Keshav.

According to Hindu mythology, Keshav says, a betel leaf garland was offered to Hanuman, a monkey god, by a goddess when he conveyed to her that all was well with her husband. She was so overwhelmed that, to thank Hanuman, she strung paan leaves together to garland him. That started the tradition of Hanuman devotees offering paan to him.

Also known as green gold, paan leaves come from the Piper betle, a vine of Southeast Asian origin that bears no flowers or fruit. Today, it is found in markets across Asia and Africa. India grows nearly 40 varieties out of the nearly 100 cultivated worldwide.

Chewing paan is popular across Southeast Asia, from Thailand to the Philippines to Vietnam. Skulls dating back to 3000BC in the Philippines show betel-stained red teeth, proving that paan chewing was common across the archipelago. The red colour comes from the slaked lime, which reacts with saliva and releases an alkaloid – a chemical compound.

Over the years, paan has metamorphosed from being a stand-alone offering to a staple ingredient for a host of foods and beverages. Kapil Sahi, the executive chef at the Radisson Hotel in Noida in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, says he incorporates paan in his food.

The paan kulfi at the hotel’s Indian restaurant, The Great Kebab Factory, is a popular dessert. “In addition, we also offer sada [plain] paan and meetha [sweet paan with gulkand] as a mouth freshener at the meal’s end. We also do paan shots at our bar. Once, I made doughnuts with a filling of chopped betel leaves and gulkand, which was well received by our guests,” Sahi says. “The possibilities are endless with paan.”

The chef recalls his fascination for the leaf as a young boy who grew up watching his dad – a paan connoisseur – enjoying it as a post-meal indulgence. “Dad also kept an elaborate paandaan [a container for storing paan] containing various condiments which were replenished promptly with the best ones available in the market. Guests at our home were customarily offered paan as a post-dinner treat or when they arrived.”

Some communities in Tamil Nadu, a South Indian state, are known to cook rice with garlic and betel leaves. Soup infused with ghee and chopped betel leaves is considered a delicacy. In Vietnam, betel leaves are used to wrap spicy meat morsels.

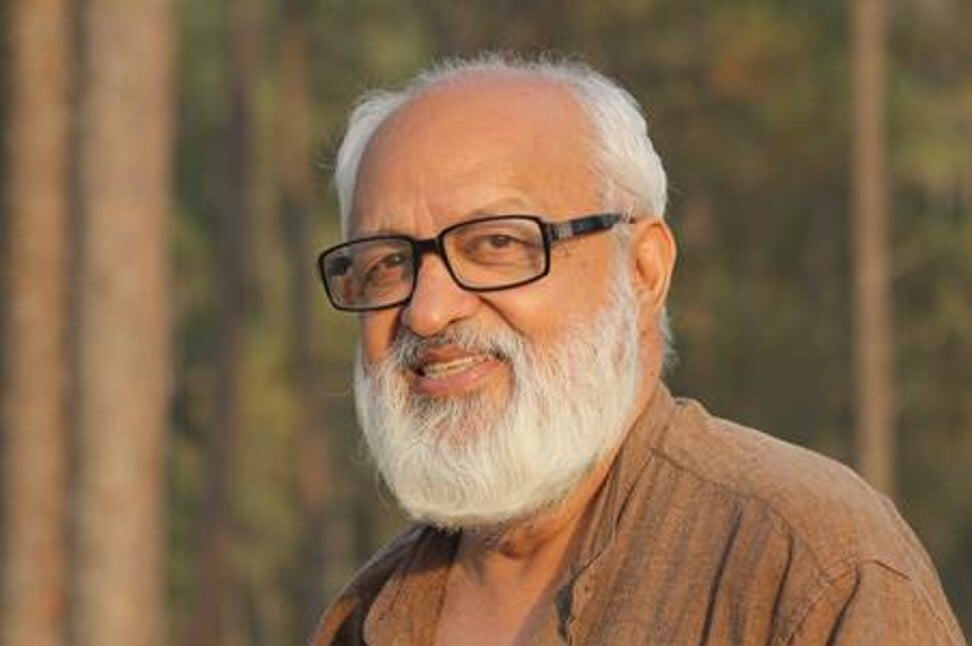

Food historian and author Dr Pushpesh Pant, who is writing a book, Paan Bakhan, on the significance of paan culture in India, recalls his father’s love for the leaf.

“My mother often teased him that he loved the leaf more than he loved her. He would just smile and wink at us children while tucking his favourite maghai paan into his mouth. He was particular about having kattha spiked with kewra [rose water] and chuna [calcium] slaked in milk, not water.

“It’s difficult to find such finicky connoisseurs these days who understand each ingredient’s flavour profile, for the finished product to have a perfect balance of taste. These days, the paan culture has been ruined by gimmickry.”

For those with a taste for adventure, there’s fire paan. A craze among Indian youth, this one combines spices, fruits and dry cloves set aflame and then thrust by the paan vendor into the customer’s mouth. Peppermint is added alongside other fillings to make it catch fire. On the other end of the scale is ice paan, which is filled with crushed ice for a cool aftertaste.

According to Pant, the maghai paan is considered exclusive because its delicate leaves grow only during four months in a year and are cultivated selectively only in Bihar (a state in eastern India), as opposed to desi patta which grows more abundantly.

In earlier days, reminisces Pant, paan preparation was an elaborate affair among the nobility that required skill and patience. Each family had a unique recipe. Some would boil the betel nut in milk, others soaked it in rose water. The ladies would bring clever innovations to put their own spin on paan making.

Special paan folding techniques were used to impress guests. The prepared paan were placed in a special covered dish called the khaas daan. Paan containers and spittoons – for the saliva generated because of the chewing – were often works of art crafted from silver and embellished with intricate designs, Pant says.

Paan has also been celebrated in Indian film. Amitabh Bachchan sang about benarasi paan in his 1978 blockbuster hit Don. The 1966 film Teesri Kasam depicted actress Waheeda Rehman crooning about her lover’s paan-stained red lips.

The leaf has also propelled some to stardom. In central Delhi, Pandey’s Paan Shop holds the unique distinction of treating all former Indian presidents, prime ministers and state guests with his paan. The list includes three US presidents, including Barack Obama.

Pandey says he offers 50 types of paan – from the plain to giant baroque confections brimming with more than 30 ingredients. Flavours range from butterscotch to kiwi, piña colada, blackberry, raspberry, walnut, hazelnut and chocolate. In a nod to diabetics, there’s diet paan as well, where sugary gulkand is replaced by sucrose – a sugar found in plants.

The history of vindaloo, Portugal’s precious gift to Indian curry

“The betel leaf is a trove of health benefits. It contains micronutrients such as thiamine, niacin, riboflavin and carotene, and is also a great source of calcium which is why we recommend it for lactating mothers. Eating betel leaf regularly helps in balancing vata and kapha doshas [regulating forces of nature] of the human body,” says Ved Shastri, an Ayurvedic doctor from Delhi.

Consuming one betel leaf a day also flushes out toxins from the system while producing the optimum balance of pH levels in the stomach. Paan is also an appetite enhancer, and betel leaf oil helps prevent tooth decay while strengthening gums and teeth, Shastri says.

Despite its glorious legacy, betel leaf cultivation has come under a cloud in India. A surge in the cost of labour and the charges for water (paan, like rice, requires a lot of water to grow) is eroding profits, farmers say.

“Earlier, water was not a problem but now, with plummeting water tables, water is not available year round and has become very expensive,” says Prakash Chaurasia, a smallholder farmer from the Mahoba district of Uttar Pradesh, a paan growing belt. “I’m not sure how long I can continue with my family profession. I’m planning to diversify into growing vegetables and herbs as well to earn better profits,” says the third generation paan farmer.