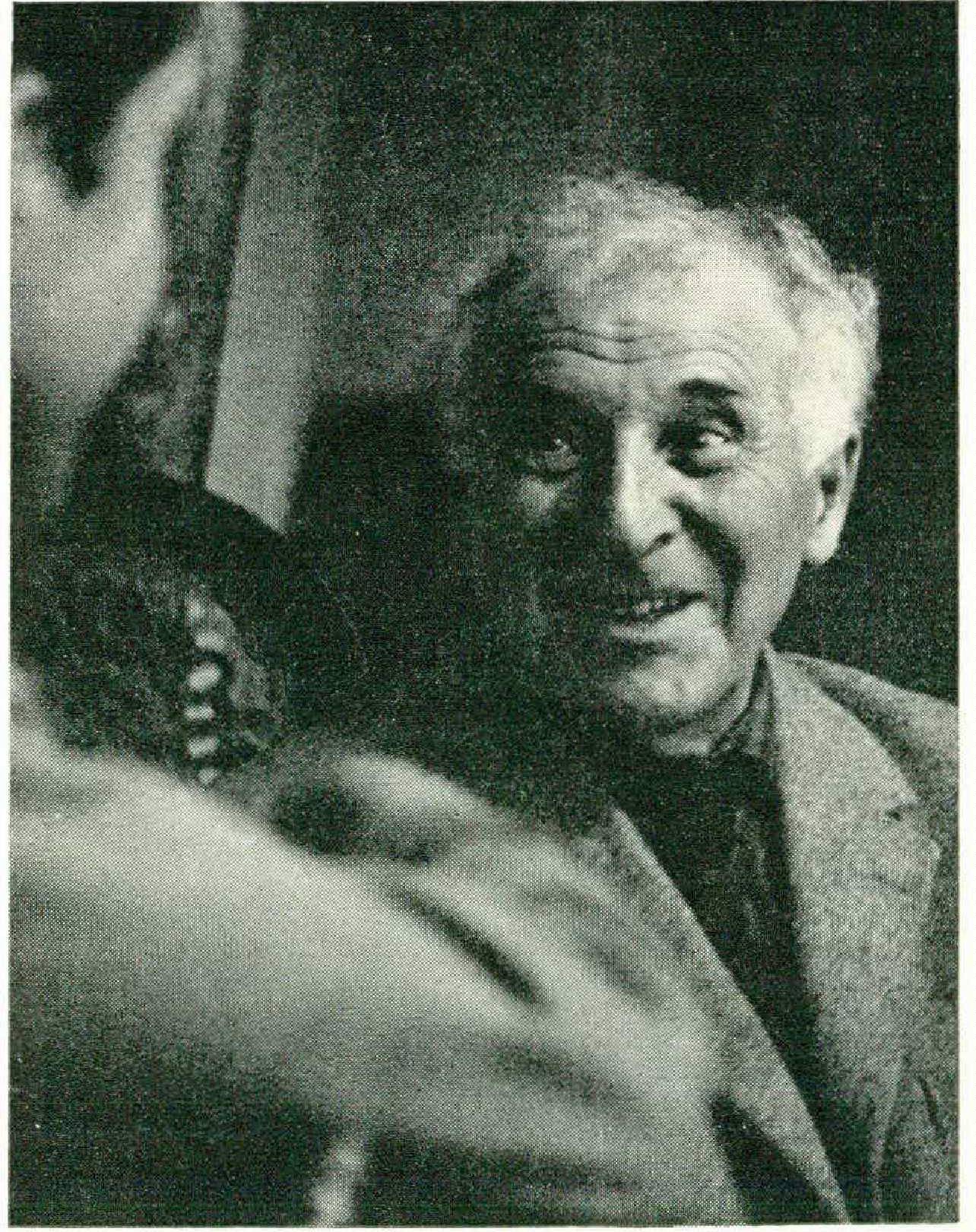

Artist at Work: Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall has lived in Paris since he left Russia in 1940. For the past five years he has devoted himself to a new medium, stained glass, and last winter invited CARLTON LAKE, an American art critic who is his neighbor, to go to Reims and watch him work.

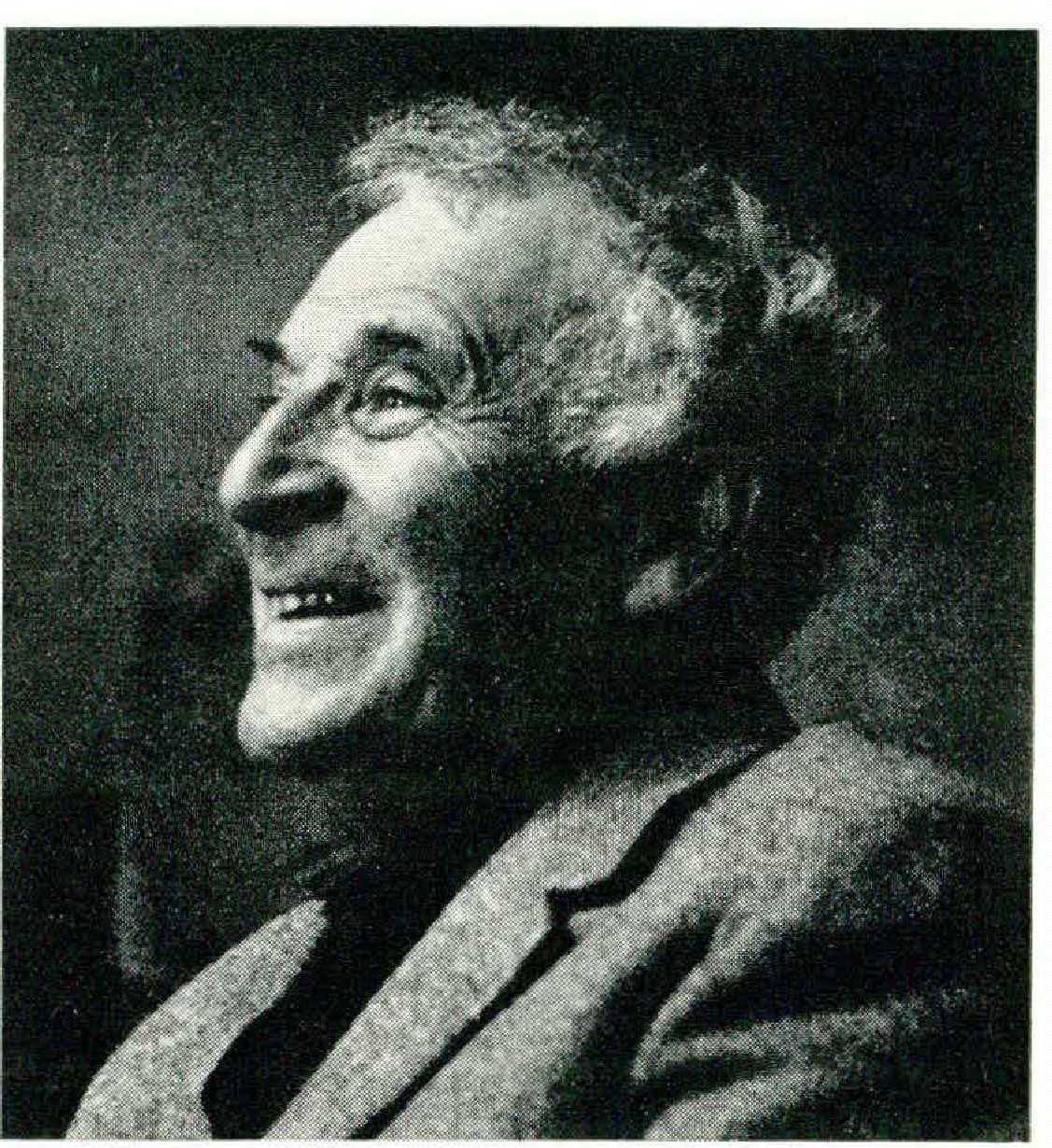

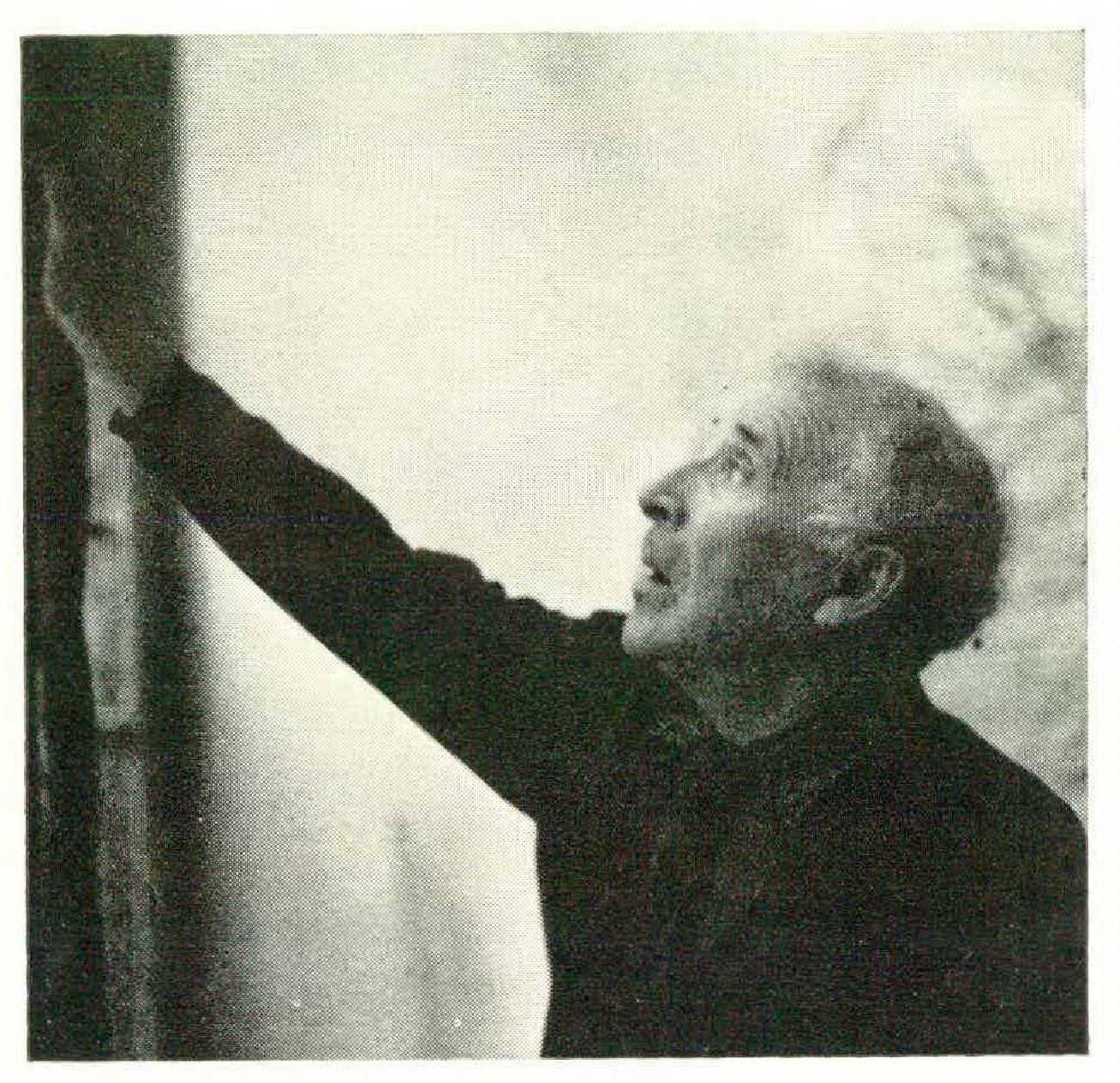

MARC CHAGALL, who will be seventy-six this month, is probably, just as one French magazine recently called him, the best-loved painter of our time, and in addition he is the most tireless worker of them all. By the time Picasso gets up, Chagall has half a day’s work behind him. And that half a day would put to shame the full day of most of his contemporaries.

Over the past five years much of Chagall’s time has gone into the creation of stained-glass windows. His twelve windows for the synagogue of the Hadassah Medical Center of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem broke all previous attendance records — including Picasso’s — when they were exhibited at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in the summer of 1961. In the autumn they were moved to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The first day, according to one of the museum’s officers, “more than six thousand people lined up to see them. After that we had to restrict attendance to keep the crowds within manageable bounds.” In all kinds of weather, the line stretched for blocks as people waited with incredible good cheer as long as two and a half hours to get into the museum.

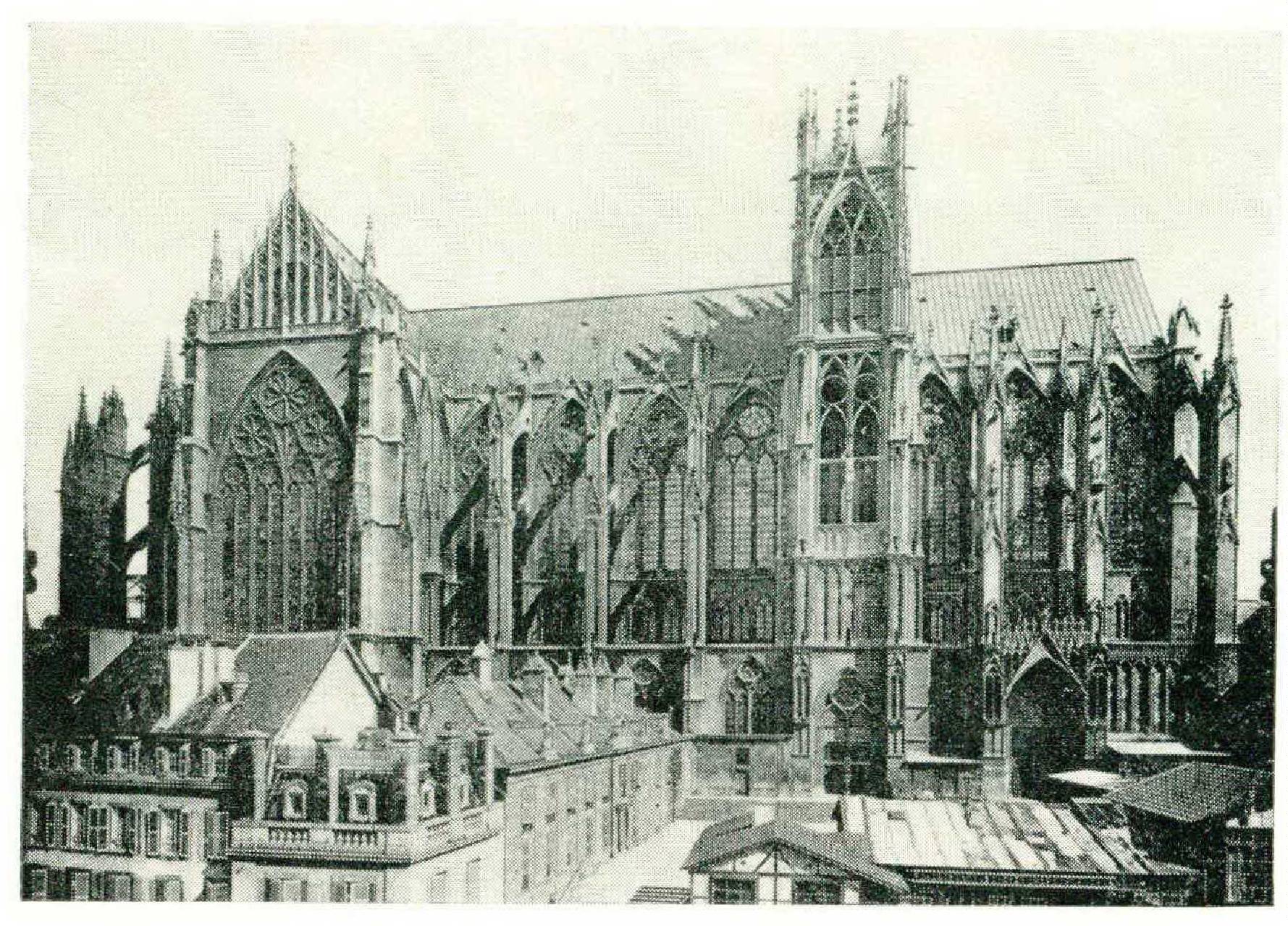

Chagall is now working on windows for the Cathedral of Saint-Etienne in Metz. One of them is already installed, another has just been completed, and a third is under way. These windows, more varied and complex stylistically and technically than the ones he did for Jerusalem, have been acclaimed by those who have seen them as the highest achievement in stained glass in modern times. The persuasive late Dominican Father Couturier induced many leading painters to take up stained glass — Matisse, Braque, Léger, Rouault, Manessier, among others — but none of them, in the opinion of most critics, have produced work that ranks with Chagall’s.

At a time when the work of even the most illustrious of his contemporaries, Picasso and Braque, has sometimes seemed to be thinning out to the point of triviality, Chagall, in his attack on this — for him — new medium, has demonstrated a creative vigor that comes close to being unique in our time.

Because we have been neighbors in Paris for many years, I have often had occasion to talk with Chagall about his stained glass. Recently, coming up to Paris from his home in Vence on the French Riviera, he invited me to go with him to Reims while he worked on one of the Metz windows. The invitation was quite unpremeditated, and he seemed almost to be apologizing for it, I thought, by telling me that it was the first time in his life that he had ever allowed anyone other than his wife or a collaborator to be with him in the studio as he worked. I didn’t give him a chance to change his mind, however, and the next evening, a Friday, I rang his bell, two or three doors down the quay from my house in Paris, to pick him up for our trip to Reims.

Vava, Chagall’s wife, dark-eyed and smiling, let me in. Chagall poked his head out of the studio. “I’ll be right with you; just finishing my letter to Ben-Gurion.” In a minute he was back. He is of medium build, with unruly gray hair and bright-blue eyes, and he has a kind of elated grin that, like his painting, has been making people happy ever since he landed in Paris from his native Russia in 1910. “Where’s my hat?” he asked.

Vava pointed to the pile on the chair. “There’s your hat, your coat, your bag, and the pheasant.”

I helped him on with his coat. It was heavy and shaggy, like an unshorn sheep. “Somebody sent me this from Germany,” he explained. I could believe it.

“You have your glasses for working? Glasses for reading?” Vava asked him.

Chagall felt in his pocket. “OK. And my hat?”

Vava handed him his hat, broad-brimmed, flat-topped, of brown corded material. “ Just be calm now,” she said.

Chagall fingered his hat affectionately. “I didn’t use to like this hat. I thought it made me look like a gigolo. But now I can’t get along without it.” He smoothed away its creases and rubbed at a grease stain or two. We went downstairs and into the waiting cab for a halting trip through the early-evening drizzle to the Gare de l’Est.

OUR compartment on the Paris-Reims express was warm and comfortable, but there were no lights on, even though it was nearly starting time. “They’re making economies. All the money goes to support Algeria,” Chagall said. Just then the train started, and a bright light was reflected from the glistening white ceiling, harsh on the eyes.

The woman sitting across from us picked up her copy of Paris Match and began to read. Chagall asked me if I had seen the current issue. I told him I never read Match, on principle. “There’s a news item in this week’s issue,” he said, “headlined ‘A Great Painter in His Place,’ and then followed by the announcement that the Israeli Parliament building will be decorated by Chagall. They refer to me as a great painter; that’s very kind, but in my place, you see. In Israel, where I belong.” He shook his head. “The owner of Match came to my last exhibition and bought a terribly expensive painting. Then he writes stuff like that. Well, I suppose he doesn’t have anything to do with that. It’s like Life. Luce runs it, but he has editors for all the different departments, and they have writers, and the right hand doesn’t always know what the left hand is up to.”

I told him I had an idea that Life’s right hand kept pretty close tabs on its left hand but I could believe there might be a little more anarchy in Match, as in most things French.

“That’s really nothing, though,” he said. “Only a little dig. But did you see the article FranceObservateur ran on me last summer?” I hadn’t. “They’re all up in arms over the plan to have me decorate the ceiling of the Paris Opéra. It wasn’t my idea. It was Malraux’s. But if they like the ceiling the way it is, let them keep it. It’s a little silly, and it fits in nicely with the rest of the Opéra. Arts and some of the other papers weren’t too pleased over the project, but the Observateur got really nasty, calling me the Bernardin de SaintPierre of the ghetto and other things like that. And in the course of the article they shouted at Malraux: ‘Don’t insult the future.’ The article was signed by somebody no one ever heard of, so everybody assumes it’s a nom de plume. But they really go out of their way to stick the knife in me.” Chagall shook his head. “It’s amazing the way the French resent the foreigner. You live here most of your life. You become a naturalized French citizen. You give them twenty paintings for their Museum of Modern Art. You work for nothing, decorating their cathedrals. And still they resent you. You’re not one of them.

“It was always that way. When Ambroise Vollard commissioned me to illustrate the Fables of La Fontaine, what a hue and cry! People wrote letters to the editor in all the newspapers. Our La Fontaine! Our national La Fontaine, illustrated by a Russian! It even went as far as the National Assembly. Deputies stood up and made speeches of protest. Vollard explained that La Fontaine had borrowed from Aesop, from the Greeks, from Oriental legends — even from Russia — and that I was just the man to tie it all up together. Finally things calmed down. But he never did publish the book, what with one thing and another, even though I completed the one hundred etchings for it in 1926. It wasn’t until 1952 that the book was brought out, by Tériade.

“And the Bible! What a stew about that! Rouault was incensed that Vollard should ask me — a foreigner and a Jew — to illustrate a book that he felt should rightfully have been turned over to him — a good Frenchman, a good Catholic, a good bourgeois. He gave Vollard a hard time about it as long as he lived. Even after Vollard died, Rouault found ways to keep on paying him back for that. Well, that’s the way they are. You can’t expect them to change overnight.”

Chagall looked at his wristwatch, shook it, looked at it again. “What time is it, anyway?” he asked me. I looked at mine and saw that it was ten minutes of eight. He looked disgusted. “This watch, a friend of mine gave it to me. It’s really a symbol of our era. It tells you what time it is in any city in the world. You don’t even have to wind it. But whenever I want to know what time it really is, I have to ask somebody. It’s full of jewels and all kinds of special mechanisms, but it never tells me what time it is right where I am when I want to know.” Chagall grunted, slumped into a corner of his seat, and catnapped. The woman opposite us pecked up over the top of her Match, then submerged again.

While Chagall dozed, I fell to wondering who would win out on the Opéra ceiling. On one side the red-hot chauvinists, the anti-Semites, nostalgiaridden Second Empire buffs, and assorted ToutParis snobs. On the other, Andr73233; Malraux. Uneasily in the middle, Chagall. If anyone were to force me to take a stand on the question, I would, if for no other reason than to augment the discomfiture of the first group, vote for Chagall. On the other hand, I don’t know that anything as preposterous as the Paris Opéra is worth the trouble. Yet Malraux can be a very stubborn man, as quite a few administrators of the Opéra and the Comédie Française and various other heeldragging cultural functionaries, some of them now unemployed, can testify. And Malraux is strongly pro-Chagall.

“Nothing like this has been seen since the Romanesque,” was what he said after his visit to the exhibition of Chagall’s stained-glass windows for Jerusalem. The windows had been installed in a temporary building thrown up for the occasion in the Carrousel garden behind the Paris Musée des Arts Décoratifs, and Malraux, as De Gaulle’s Minister of State for Cultural Affairs, had come to open the exhibition officially. Whether in that capacity or as France’s leading maverick art historian or simply as a man with a passionate interest in art who has been an admirer of Chagall’s work for more than thirty years, he was certainly not prepared for the visual shock the windows gave him. Nor were thousands of others among all those who flocked into the museum gardens during the summer of 1961.

Chagall had taken four basic colors of a specially processed glass — red, yellow, green, and a blue that is exclusively his — and created a symbolic representation of the twelve tribes of Israel; not an illustration of them, but a transposition in terms of pure color and the flowers and animals of his own private kingdom, a rather unorthodox realm theologically, that partakes of both heaven and earth. There were references to his Old Testament background — the seven-branched candlestick, the Torah, the Star of David, Hebrew lettering, and other recollections of his Orthodox upbringing in the ghetto of Vitebsk. Hands holding the shofar and an occasional disembodied eye are the closest he comes to human imagery. All twelve windows are peopled by fish, birds — some wearing crowns — now and then a serpent with flickering tongue, horses, goats, and various other animals of rather ambiguous ancestry, and by flowers and plants of all kinds. And when light filtered through that color and those forms, it was enough to, well, make an uninnocent eye like André Malraux’s reach back eight hundred years to the Romanesque for a point of comparison.

Chagall worked on those windows over a period of two years with the technical assistance of Charles Marq and his wife, Brigitte Simon, in the Atelier Jacques Simon in Reims. In order to do them, he interrupted work he had begun on his windows for the Cathedral of Metz. Now that the Jerusalem windows are in place, he has gone back to work on the ones for Metz.

WE REACHED Reims at 8:15, left the train, and made our way through the crowds to the parking area, where Charles Marq was to meet us. “There’s Charles Marq now.” Chagall pointed to a small, slender blond fellow in his late thirties, hatless but wrapped up to the ears in a camel’shair coat, its collar turned up against the chill. He had a long, narrow face that in repose looked sad, like a tired child’s, but when he saw Chagall his eyes lighted up and his face creased into smiles all over. “You didn’t think I’d show up, did you?” Chagall said.

“Oh, I’d have banked on it. I know you.” Charles Marq grinned over at me. “Just try to keep him away.” We piled into his ivory-colored Volkswagen, and he drove off across the wide cobblestoned streets of Reims toward the Atelier Jacques Simon.

The origins of the Simon family as master craftsmen of stained glass are obscured by the absence of records. Some say they were functioning before there was a cathedral in Reims to put their windows into, and the cathedral had been there for over a hundred years when Joan of Arc came along. In any case, what is clear is that a Simon was turning out stained-glass windows at the beginning of the seventeenth century on pretty much the same spot that the Atelier Jacques Simon now occupies.

The Volkswagen came to a bumpy stop, and we all got out. The building, four stories high with a wide facade of glass, stucco, and round stones set into cement, has a properly Romantic if not quite medieval air about it, with just a touch of William Morris. Over the front door I saw a rectangular mosaic that proclaimed ”Travaux d’Art Décoratif.” Chagall and I set down our bags in the hall; he removed a bulky package wrapped in white paper from his, and we followed Charles Marq up the first flight. At the head of the stairs, Charles Marq turned to Chagall. “Want to take a look?” Chagall shrugged. “I don’t mind.”

Charles Marq opened a door on our right, and we filed into a high-studded atelier whose front wall was all windows up to a ceiling about twentyfive feet high. There was no light except the dim blue-gray reflection of the streetlights outside. On a black-shrouded metal framework in front of the high windows were two lancets of stained glass with pointed tips. I could see dimly that the imagery was Chagall’s, but since stained glass doesn’t come to life until it is pierced by light, I got no clear idea of the subject or composition of either one.

“They’re all ready for you, you see,” Charles Marq said.

“Maybe. We’ll see about that tomorrow,” Chagall said. We left the studio and climbed a drafty, winding stairway to the floor above. We passed through an anteroom into a small cheerful sitting room with a log fire burning brightly in a freestanding white-painted brick fireplace. In the far corner was a table set for four.

Through a door on the opposite side of the room, Brigitte Simon came in. Brigitte, in her midthirties, is tall with a narrow face and high cheekbones framed by dark-brown hair parted in the middle — a Pre-Raphaelite painting reinterpreted by Aubrey Beardsley. Her long, sinuous body gives an impression of strength and agility. She kissed Chagall and took the bundle he held out to her. “I brought you a pheasant,” he said, “but his wings are clipped.”

“Just so long as yours aren’t,” she said. “That’s all that matters.” She disappeared with the pheasant and returned with a bottle of champagne. We sat down to a dinner of trout that hadn’t been out of the water many hours.

“Do you have help for tomorrow, Charles?” Chagall asked. Charles Marq nodded. “Michel’s coming in. He’s not supposed to work Saturdays, but he’ll be here.”

“He’s a nice boy,” Chagall said.

“He likes you. He likes to work when you’re here.”

Chagall picked at the edge of his trout and left his glass untouched. The door nearer to us opened, and two small heads peeked in. “Come say hello and good night,” Charles Marq said. Benoît, a tall, dignified eleven, and Charlotte, a very bright-eyed Kate Greenaway eight, made the rounds with kisses and handshakes and were promptly shooed off to bed.

Chagall looked at his watch, trying to figure out what time it was in Reims. After consultation with the other watch wearers present he decided it was bedtime. Charles Marq drove us to the Grand Hôtel du Lion d’Or; we agreed to rendezvous in the lobby at eight in the morning, and went our separate ways.

I GOT down to the lobby at ten minutes to eight the next morning, but I found Chagall and Charles Marq waiting by the entrance. When we reached the studio, the light had barely begun to filter in through the high windows, and the two lancets were not much more than faintly visible from the back of the atelier. Chagall walked over to the lancets. “What time does the light come in?” he called out.

“In about half an hour,” Charles Marq said. Brigitte, in black stretch pants, was vigorously preparing Chagall’s paint on a small rectangular table between the two lancets. Chagall took off his coat and suit jacket and pulled on a black-andwhite-checked lumber jacket. He fumbled unsuccessfully with the zipper. “It’s modern. No buttons,” he grumbled. Brigitte came over and zipped him up.

Charles Marq, now at the little table, tested the paint. “It’s much too liquid, Brigitte.” Brigitte returned to the table and worked at the solution to bring it to the proper consistency.

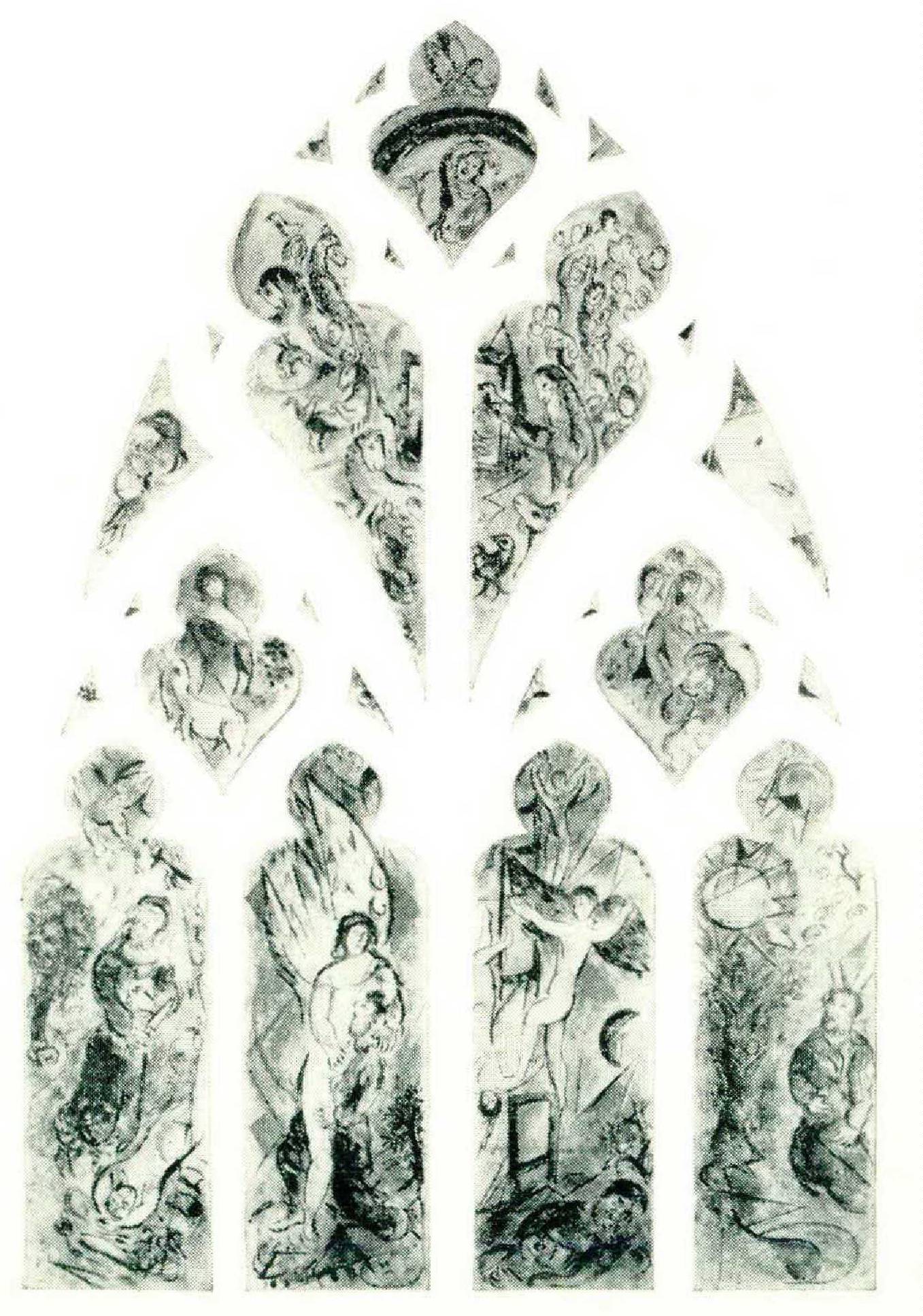

Propped up on a large easel at the left of the two lancets was Chagall’s final maquette for the window, which was painted in gouache on a one-toten scale and arranged against a white background, framed, and covered with transparentplastic protective sheeting, showing the design the window would take when installed at the Cathedral of Metz. The maquette as a whole had the pointed-arch form of a Gothic ogive. The main body of the window was composed of four parallel lancets at its base, separated by white strips representing the stone into which they would eventually be set.

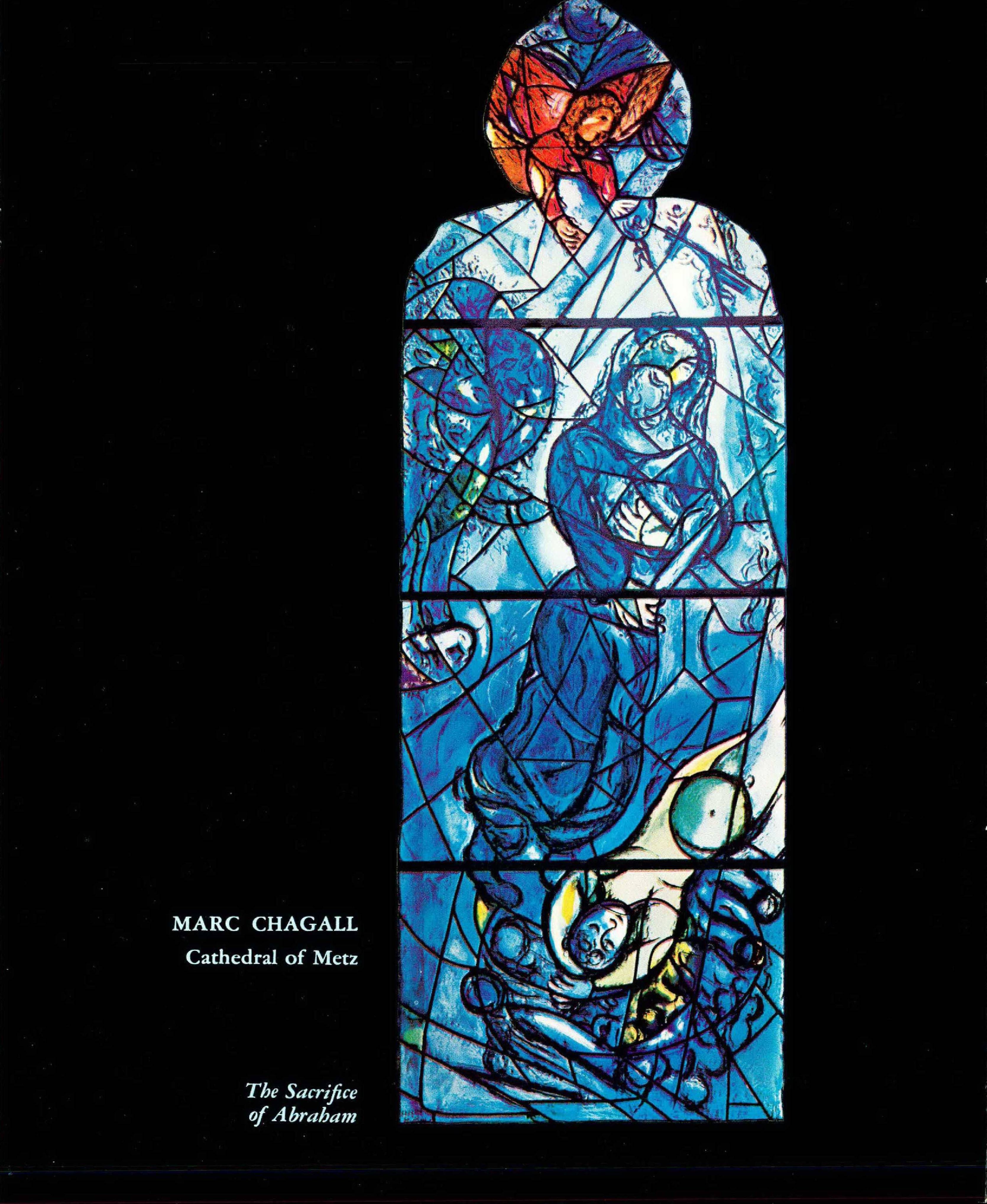

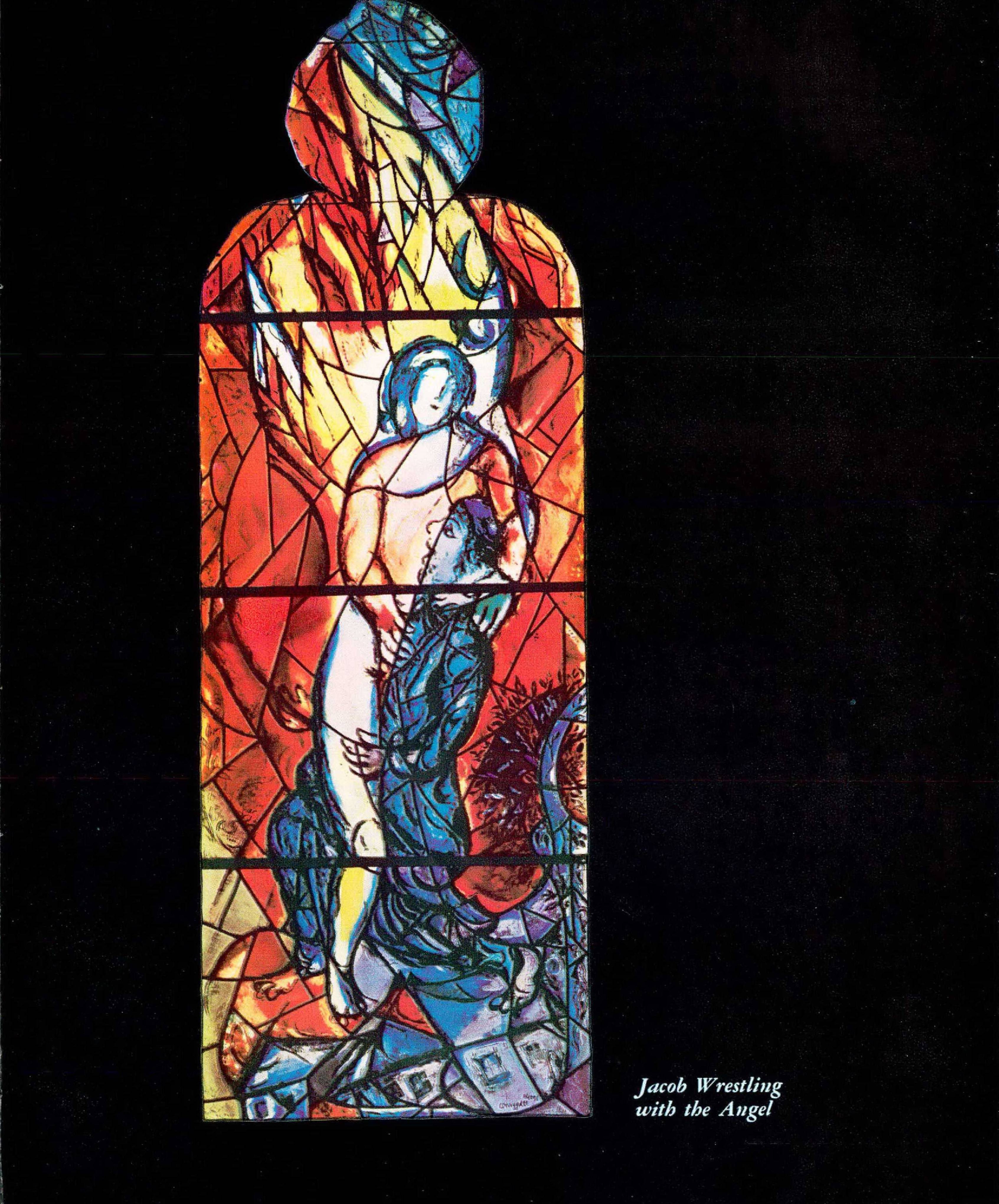

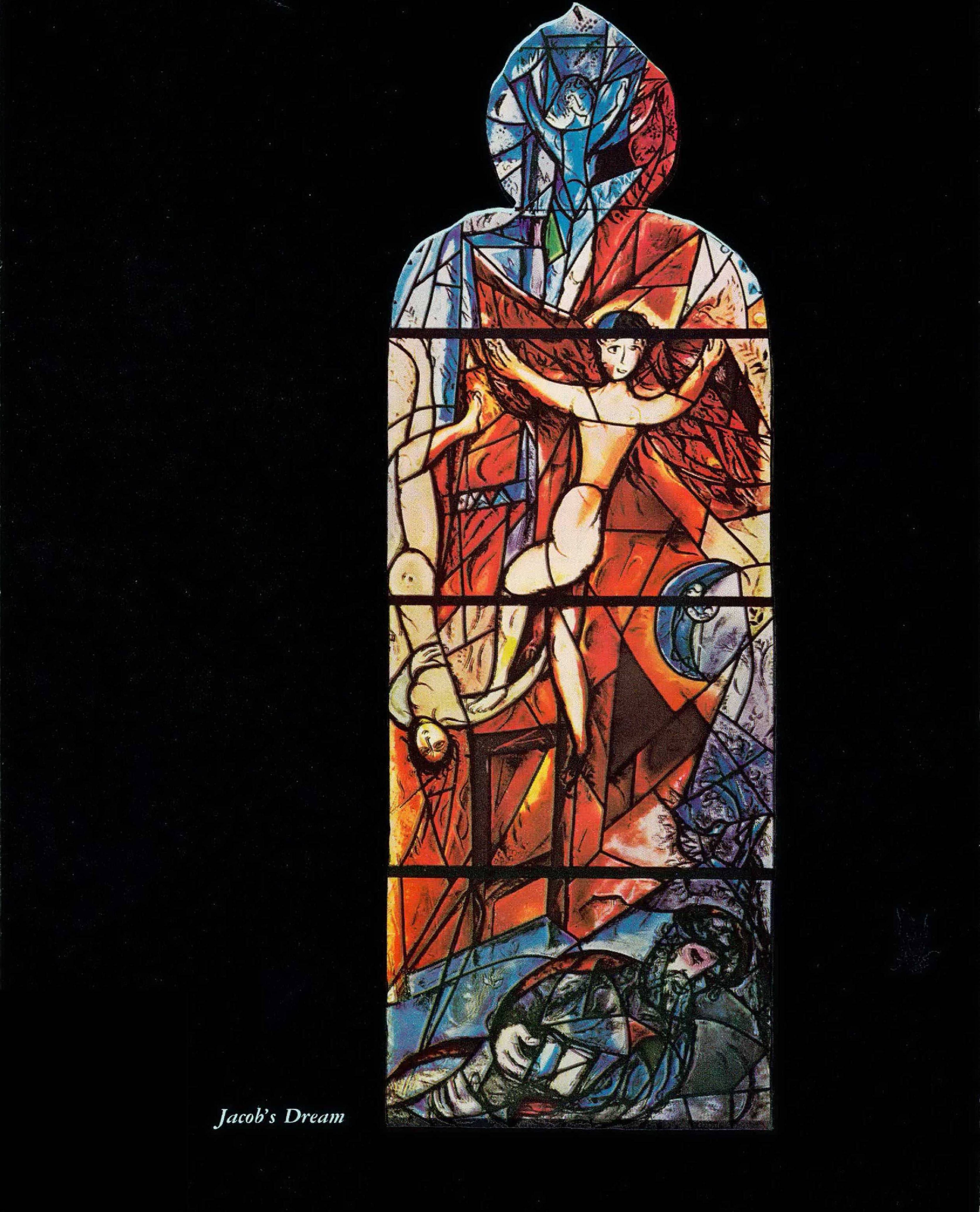

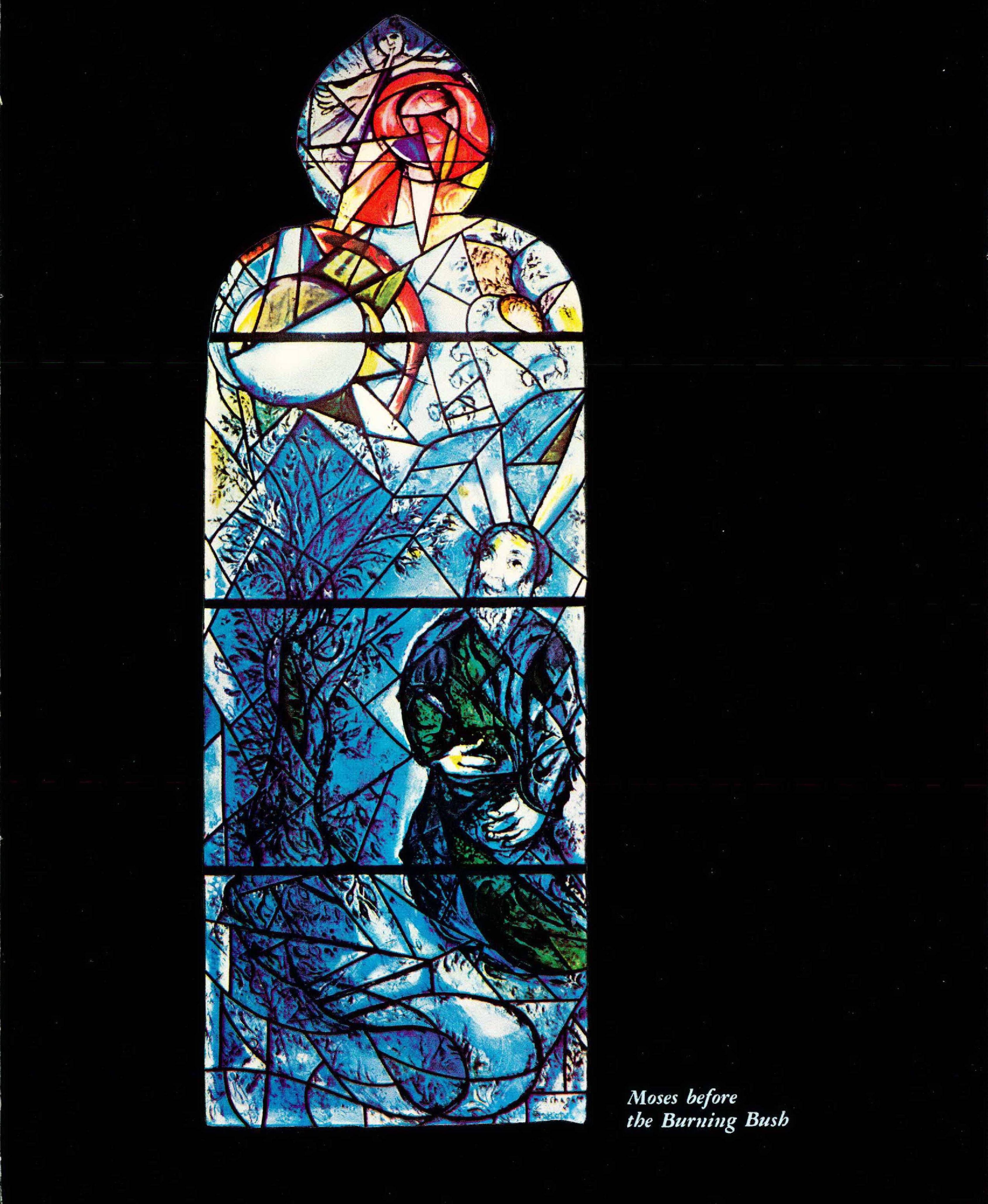

Chagall, half a dozen brushes in his left hand, saw me studying the maquette and came over to join me. “That one” — he pointed to the lefthand lancet — “is ‘The Sacrifice of Abraham.’ The one next to it is ‘Jacob Wrestling with the Angel’; the one next to that, ‘Jacob’s Dream’; and the fourth one, on the far right, ‘Moses before the Burning Bush.’ ”

Directly above the four lancets were two smaller units of the design, each in the shape of a heart, but having, like the lancets, an ogival point at the top. The one on the left showed a boy with a sheep in front of him. “That’s Joseph,” Chagall said. “And on the right is Jacob, weeping for Joseph.” He pointed up to two similarly shaped but longer parts of the design that were set in between the two heart-shaped pieces but rose almost to the top of the maquette. They were crowded with a variety of human and animal figures. “Noah’s Ark,” he explained. “And on top” — he pointed to another element above them that formed the very tip of the maquette and had the same form as the two lower heart-shaped parts — “that’s Noah after the Flood.” Over Noah’s head was a rainbow, and over the rainbow an angel. Set into the white areas that separated all these elements, from the points of the lancets to the top of the maquette, were eighteen curvedsided triangular shapes of varying sizes that filled out the design. “The whole window will be a little over twenty-three feet high,” Chagall said.

The two lancets that were set up on the metal racks were, on the left, “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel” and, on the right, “Jacob’s Dream.” Each one was about ten feet high and forty inches wide, divided into three rectangular panels and a fourth one. higher than the others, that ended in a point. Their metal edges were secured to the framework with clothespins, and black cloths draped around them allowed the light from the studio windows behind them to enter the room only through the stained glass itself. The left-hand lancet showed Jacob down on one knee, struggling with a largerthan-life-size angel whose form, together with Jacob’s, filled the central area of the lancet and whose wings, a pale yellow flecked with brighter tones, swept upward into the point of the lancet. The flesh tones of the angel and the blue of Jacob’s body were sharpened by the warm red of their background. Behind Jacob was a small bouquet of flowers.

“I finished ‘Jacob’s Dream’ last week,” Chagall said, “but there’s a lot of work to do on the other one still.” He went over to the lancet that showed Jacob wrestling with the angel, sat down on a low stool beside his table, selected a small brush from the ones in his left hand, dipped it into the paint, and started to work.

Brigitte, I saw, was working with two wide brushes over the surface of “Jacob Wrestling.” With one, which she dipped frequently into the grisaille — the black liquid paint she had earlier been mixing on the table — she was covering the upper panels with broad strokes. With the other, apparently dry, she removed the excess and whatever clung to the leads, giving in this way a fairly uniform thin grayish film to the surface of the glass. Her long legs and arms were moving efficiently around Chagall, who seemed planted in front of his lancet like a tree rooted in the ages. Utilizing the him of grisaille that Brigitte had already washed over the lower panel, he was painting in accents, small figures, and flower and leaf forms.

He had begun, lightly and gently, in the lower left-hand corner, until then populated chiefly by Jacob’s and the angel’s right feet. Now he had worked over to the right center, near the spikv bouquet, and was working faster. The glass rattled in its frame. One of the clothespins popped off onto the floor. Chagall stopped, studied the bouquet for a moment, then picked out, with a finger, areas between some of its clusters where the grisaille was still wet, to vary the effects of shading. He painted in new forms, neither animal nor purely vegetable, through whose presence what had been colored glass became matter in movement. He was working rapidly now, ranging widely from the bush to Jacob’s beard to the angel’s aureole and back to Jacob’s beard again. Behind us, in the center of the atelier, the high old-fashioned coal stove had swung into its stride, too, and in spite of the twenty-five-foot ceiling, the temperature was rising by the minute. Chagall peeled off his lumber jacket and tossed it onto a chair. Almost in the same sweep of his arm he returned to the glass and attacked the angel’s wings.

“Charles,” he called out, “my glasses are steamed up.” Charles Marq came over, lifted off Chagall’s glasses, wiped them clear, and replaced them. Chagall didn’t stop working. He sat down on a small chair near the painting table and began to pick out, with his finger, some of the shaded areas around the bouquet. The deep-blue central stem and the dull garnet of the background began to glow with new warmth.

CHARLES MARQ came over with a young fellow in a long gray workcoat.

“Ah, bonjour, Michel,” Chagall said. “You were very nice to come in on your day off.”

“You aren’t doing anything more on ‘Jacob’s Dream,’ are you?” asked Charles Marq.

Chagall shook his head. “No, I think it’s all right the way it is. I’m leaving it like that — at least for now. If I did anything more on it, it would be in a different spirit, so I’d better leave it alone.”

“Good,” said Charles Marq. “I want to get it into the kiln. If you want to make any additions, you can do that afterward.” He and Michel started to dismantle “Jacob’s Dream,”which was principally in warm tones of rose and red with touches of blue, green, and yellow. They removed first the bottom panel, about two and a half feet high by three and a half wide, with the figure of a bearded Jacob asleep. They then removed the panel next above, which, with a similarly shaped panel above it, and the point of the lancet above that, showed the angels of Jacob’s dream ascending and descending the ladder. In the center, to the right of the largest angel figure, was a crescent moon in which Chagall had painted a worn peasant figure with a pack on his back. Underneath, on a branch of the bush at Jacob’s head, was a tiny bird. They removed the third panel and then the point. They stacked them against a wooden rack at the rear of the studio.

Chagall, I saw, was picking out, with the wooden tip of his brush, spots of light in the grisaille around the perimeter of the bouquet behind Jacob. I asked him why he was digging into the grisaille like that, making hundreds of tiny marks in the film. “That makes it vibrate,” he said. “And it makes a marriage between the bouquet and the upright composition in the center — Jacob wrestling with the angel. It brings them together. You’ll see.”

Charles Marq came over to us. “If the bottom panel is done,” he said, “you might as well sign it so we can take it downstairs.” Chagall moved from his chair onto the low stool, dipped a brush into the paint, and signed his name in the lower right-hand corner.

“That’s too low,” Charles Marq said.

Chagall rubbed it out and wrote it in a bit higher. “You’re sure it won’t run, your ink?” he asked.

“That’s too small,” Charles Marq said. “You’re too modest.”

Chagall looked up at him. “How do you spell ‘Reims’?” he asked.

“R-e-i-m-s,” Charles Marq answered.

Under his name, Chagall wrote R-i-e-m-s.

“Not like that,” Charles Marq said.

Chagall looked up at him. “What do you mean?”

“Nothing,” Charles Marq said. “That’s all right. It makes no difference.” He moved the painting table aside, knocked over a glass, and spilled water onto the floor. He cleaned up the mess, pushed the table out of the way, and spilled the water again.

“Don’t touch my color,” Chagall said.

“Matter in revolt,” Charles Marq said. “Rebellious neutrons.” Chagall went back to work on Jacob’s head.

MICHEL came in with the sections of another lancet and began to set them up in the frame that earlier had held “Jacob’s Dream.”

“This is ‘The Sacrifice of Abraham,’ ” Charles Marq said to me. “Chagall hasn’t seen it yet.” He and Michel mounted the four panels onto the frame, pinned them against the supporting wires with clothespins, and draped the black cloths above and on each side to shut out the light. Chagall left Jacob to the angel and walked over to study Abraham. The central figure, a hesitant and grief-stricken Abraham, holding a long knife in his right hand, stood over the naked body of his son Isaac, ready for the sacrifice. Behind Abraham was a flowering tree; over his head, a small figure of Christ carrying His cross, and looking down on Him from the point, an angel. After a minute, Chagall went back to his maquette, looked at it carefully, then returned to the new lancet, which was mostly in blue except for the naked body of Isaac stretched out at his father’s feet.

“It needs more warm tones, Charles,” he said. Charles Marq suggested adding more yellow to the body of Isaac. “That’s not enough,” Chagall said. “I want more in other places than just that body.” He pointed to two pieces of purple glass on the lower right. “That’s too dark. I don’t need that,” he said. “Put in another lead there with something warmer And a touch of green.”

Charles marked with a grease crayon the pieces of glass Chagall had asked him to change.

“It needs more light up there at the top, Charles, near the angel.”

“I’ll put in a more intense red,” Charles said.

“And more light up there on the angel’s wing. And calm it down in back. Poor man. I make you suffer, no?” Chagall kept studying the lancet. “We’ve absolutely got to have three pieces of green up there in the left shoulder,” he said. “We have to light up all those blues. And three pieces of warmth in there, too. And take out that violet. I don’t need it.”

Charles Marq looked over at Chagall’s maquette. “It’s violet on the maquette,” he said.

“Something warmer,” Chagall said. “A little more red. And up there, on the left, in the tip, behind the angel, it needs to be broken up. Another lead, no? It’s a little monotonous, all that. And it’s too dark.”

“All right,” Charles Marq said, “we’ll take care of that. I’ll engrave it. That will lighten it.”

“And give it more warmth,” Chagall said. “It looks a little too much like Matisse, as is.”

“You’re right,” Charles Marq said. “It’s a little flat — Montparno.”

Chagall shook his finger. “If it’s done very, very, very, very, very well, that’s all right. If not, it’s no good.”He ran his hand down Abraham’s robe to his feet. “I want there to be some warmth, a sort of envelope, right down to his feet. That’s all. Good-bye.” Charles Marq and Michel took the panels down to the workroom below to make the changes.

Chagall walked back to the Jacob lancet and began to brush on vigorously more of the grisaille in the area around the angel’s head, then removed some of it with the dry brush. He reversed his brush and began scraping with the wooden tip to heighten the nuances in the shading of Jacob’s body. The glass rattled and squeaked and squealed. I began to wonder just how resistant it was. Chagall sighed, grunted, and groaned, then pressed his left index finger against Jacob’s left cheek to lighten a blue area. He pulled away the grisaille from the rose of the angel’s body and then from the pale-blue shadows of its face and ran his finger glancingly down the shading of the angel’s right thigh. He stopped, inspected his work briefly; then with the palm of his right hand modified the imprint of his finger and smoothed out the impact of his earlier shading along the entire thigh. He then moved over onto the angel’s left arm, first with two fingers and then with his fingernails, lightly, caressingly.

“You see how it is,” he said. “Stained glass is like the body of a woman. It needs loving attention over every square centimeter.” He took his brush and went all over Jacob’s body, darkening the shadows. He turned and looked behind him at the photograph of the maquette. (The maquette itself had been moved below for use in making the changes on the Abraham panels.) He brushed more paint onto Jacob’s body, looked again at the photograph, applied more paint, sighed, walked over to the easel, and pulled it closer to the glass. He reached for another brush and dug in hard to scrape away some of the drying grisaille, his arm moving rapidly from one part to another of Jacob’s body and then to the angel’s. He changed his brush, dipped into the paint, and swabbed it loosely onto the lower panel.

The light was higher now, and the glass began to glow: Jacob blue, verging on purple in places; the angel pale rose with blue shadows around the head, green along the left hand; the background all in warm tones of red; the bouquet behind Jacob red with a purple-blue stem running through it. Chagall sucked in his breath and reached out with his brush to modify some of his shading, his mouth working as excitedly as his hand. The stove was hissing, and in the back of the studio a white pigeon in a high-domed wire cage craned its neck, not to miss a move. Chagall laid on a heavy black line along the shadowed blue and green behind the angel’s left arm. With the wooden tip of his brush he removed some of the shadows on Jacob’s neck. He studied the photograph for a moment and then painted in lightly Jacob’s shoulders and chest.

IT WAS now 10:45. Brigitte came in with a tray of coffee things and set them down on a long table on the far side of the studio. She called to Chagall. He kept on working. After a minute or two he stopped. “Oh, well. I didn’t get very far. Tant pis.” He threw his checked lumber jacket over his shoulders and sat down at the end of the table. Brigitte sat at the coffee tray, and I between them.

“It’s not too strong?" Chagall asked as she began to pour.

“Just the way it always is,” she said. She handed us steaming cups of coffee and spread slices of toast with butter and honey and passed them to us. Chagall took a bite, sipped his coffee for a minute, then turned to me.

“Well,” he said, “you’re present at the accouchemerit.” I told him this was one accouchement I was enjoying.

”I never let anyone into the atelier while I work — never. But now you’re seeing the whole damned cuisine. As you see, I don’t have any method. As soon as art becomes method, it’s finished. I just do what I have to do, what I feel here” — he touched his heart. “It comes down here” — he ran his left hand down his right arm onto the right hand. “Like an idiot, maybe, or like a child, like your little boy who does whatever comes into his head, without reflection. It’s childlike, but not childishness. Isn’t that right, Brigitte? As children go, I’m a child.” Brigitte smiled and poured us more coffee. Chagall stirred in a lump of sugar. “Nobody’s more of a child than I am,” he said. “All the others, compared to me, are people who struggle.” Brigitte spread another tartine with honey and handed it to him. ”Voilà, mon enfant,” she said.

Chagall finished his coffee and tartine. We walked back to Jacob. “ Jacob is wrestling with the angel,” he said. “I wrestle with Jacob and the angel.” He picked up his brushes and went back to work on Jacob. “ Everybody has been after me to write the second volume of My Life, to bring it up to date from 1923. I’d like to, but I’m tired. I have no more strength. Besides, it’s not my métier. Maybe I’m lazy. I just don’t get to it. I go on pecking away, pecking away. It’s a form ot madness, idiocy. But what else can I do? On this little planet, in our little world, probably the smallest of all, of millions of others, what makes sense? Friendship, a woman to love, making a child, not piling up too much false intellectuality and pride of life. Look at Gide. He died like a dog, and nobody reads him anymore. Nobody but a few pederasts. Look at the Spaniard. He spits on God. God will spit on him soon. God, who made all the millions of planets, will spit on him because He’s the stronger. Yes, the Spaniard with all his millions and all his Kahnweilers and all the rest, God will spit on him, just the way He’ll spit on Khrushchev. But He doesn’t spit on children, like your boy. The child is the genius, not all the knowledge a man piles up, because God is always stronger.”

Charles Marq joined us at the Jacob lancet. “Well, Charlot,” Chagall said, “how goes it down below?”

“It’s coming along,” Charles Marq said. “A little time, that’s all.”

“I wondered if you weren’t pulling something on me,” Chagall said.

Charles Marq laughed. ”Oh, no. Not this time. Every once in a while I rebel, though.”

“But you like it, don’t you?” Chagall said.

Charles Marq smiled. “Of course. There’s always a purpose in the changes you have me make.”

“He’s a wonderful boy, that Charles,” Chagall said. “He knows I’m a child, and I know what I want. A child always knows what he wants, even if it’s just a piece of bread and butter.”

“That’s the way it goes,” Charles Marq said. “We show him the work. He says, ‘I want this, that, and the other.’ Then afterwards it’s still not right and —”

Chagall interrupted him. “I like to listen to other people’s opinions. I don’t always follow them, but I listen. The only man I wouldn’t listen to is the Spaniard. I would never listen to him.”

Michel came in with the lower panel of “The Sacrifice.” Chagall looked over at it, dubiously. “What’s this little bit here?” he asked, pointing to a touch of red at the end of the fagots beneath Isaac’s body. “Can’t you get rid of that?”

“Oh, no,” Charles Marq said.

“You’d better put in a lead there, and I’ll make you a gift of the color.”

“But that corresponds to what you’ve shown on the maquette.”

“You don’t need a big piece,” Chagall said. “You give me something warmer. Look, mon petit, that can continue on — ah, no, there’s no lead there. Well, you put in another tone, warmer.” He coughed, like a lion roaring, and returned to the Jacob lancet. He began painting along the right-hand border. “No still lifes with a bottle here,” he said. “I make flowers because they’re divine.” Chagall chuckled. “ ‘A great artist, where he belongs.’ That’s funny, you know, because my wife is against my specializing in Palestine. She’s not nationalist. And I’m not either. But I love the Bible, and I love the race that created that Bible. And I’m not going to buy myself a place in the French Panthéon by refusing to work for those poor people in Israel if they want me.

“In any case, the French will say the same thing about me whether I work for Israel or not. Chagall belongs there, they’ll say. It’s in their blood. That’s the way they are. And I’m not going to do something or refuse to do something else in the hope that the French will think more of me for it. I do all this for nothing. I give paintings free to the Musée National d’Art Moderne, for France, not for other countries. And what happens? It’s a little like Don Quixote. Of course, they sugared the pill a little. At least they said, ‘A great artist’ — but over there, in Israel, where he belongs.”

CHAGALL stopped painting and turned to me. “You know what I’d do if I had my way? I’d never paint another picture to be sold. I’d never have another exhibition in a gallery, in Paris or anywhere else, where people come in and lay down a wad of bills to buy a picture of mine either to decorate their apartment or because they think it’s a good investment. I’d spend the rest of my days painting the Bible, as I see it, and if I have the strength and the time, leave a message — my Messages Bibliques. You know, the mayor of Vence got elected to office because he backed a citizens’ petition that proposed the town create a center for my Messages Bibliques. His opponent was against the idea, and he got beaten. So now the town has appropriated land for the purpose. All they need is a building to house everything.

“At first they offered me an old seventeenthcentury chapel in the Chemin du Calvaire. It belongs to the town, but the Church has the right to hold Mass there. But I didn’t want that. I want to inspire a religious feeling in my own way by giving a message, but I don’t want priests or any ties with formal dogma — Catholic, Jewish, or any other kind. I just want to create an atmosphere for meditation and spiritual peace. Abstract painting is the expression of the absence of meaning. I want to encourage a return to true values through the Messages Bibliques.”

I asked Chagall if he felt the center had to be in Vence. “I say Vence because I live there,” he said, “and I’ll remain there, perhaps. If I lived in Woodstock, New York, it would be there. If I lived in Reims, it would be here. Otherwise it might be Jerusalem, Paris, New York City, or Vitebsk. But maybe that’s something to think about. Should it be in Vence for just that reason? Tériade gave Vava the idea of building the place ourselves. Just like a house, a Provencal mas, very simple. There’s enough land. I bought another strip along the road in front of our place in Vence to prevent them from putting up an apartment building. I don’t think it would cost more than forty or fifty million francs to build the right kind of place. I know exactly the dimensions it would need to house everything. I’d like to have a room for stained glass, another room for the Song of Songs, and so on. Poor Vava, all that will make her grow old, perhaps. It bothers me.”

Chagall sat down and leaned over the back of his chair. “That painting of Paradise you saw last summer in my exhibition at the Galerie Maeght — Maeght would give tens of millions for that, but I won’t sell it. All those paintings and other things form an army when they’re together, but if they’re scattered here and there, they’re just individual soldiers. You can’t win that way. I’m against museums. But a message, one can leave. If these things have value, they’ll create their own museum. And if they’re kept together, that makes a little army. You can do battle with that. But if one part is in Australia, another in Boston, a third somewhere else, it’s not the same. El Greco gains strength because his work is collected in Madrid and Toledo. What I want to achieve more than anything else is my Messages Bibliques, and as soon as possible, so that those things won’t be sold left and right.

“Sometimes I think it would be nice to have the Messages Bibliques in America. I love America. People there are frank. It’s a young country with all the qualities and faults of youth. It’s a delight to make love with people like that. But my exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York was seventeen years ago. They’ve had three Miró exhibitions in that time; three or four of Picasso, but not any more for me.” I reminded him that only a year or so ago his stained-glass windows for Jerusalem had drawn an awful lot of people into that museum.

“That was something special,” he said, “but still, you can’t buck the pressure groups and the money lined up behind abstract art. Maybe the Messages Bibliques should be in Palestine, no? Of course, it’s not a very central location.” He sighed, then turned to the glass and dipped his brush into the paint. “There’s so much work to do to get any result, to take a stained-glass window and give it life. You have to embrace it, warm it up. You can’t deceive God. He wants all our juice. Well, let’s work. Let’s work.” He began to work at some of the tiny flowers at the righthand edge of the window with the wooden tip of his brush.

JACQUES SIMON, Brigitte’s father, came into the studio, a tall, dapper, bald-headed man of about seventy, with a narrow gray mustache, who for no easily definable reason looks as though he ought to be master of the hunt somewhere in the Virginia tidewater country. But the record shows that he is a painter and master craftsman in stained glass who headed up the family business in Reims from just after the First World War until his son-in-law took Over.

“It’s extraordinary, that affair,” he said. “I’ve never seen anything like it in this métier. And it’s very troubling, Jacob and the angel.”

“It will be later,” Chagall said. “But it’s like squeezing a lemon. You don’t get all the juice the first time. You have to keep on squeezing.” He went on pecking away with the tip of his brush. “I just go on doing little things,” he said.

“That’s right,” Jacques Simon said, “but they have so much importance, those little things.”

“That’s it,” Chagall said. “The world is made up of millions of planets, billions of them, so what else is there to do but go on pecking away? We have to justify our existence somehow.”

“It’s very beautiful,” Jacques Simon said.

“So I keep pecking away,” Chagall said.

“Picotons,” said Jacques Simon. He walked quietly, almost reverently, out of the atelier. Michel came in, carrying the bottom panel of the Sacrifice lancet. He set it back in its place on the frame. After he had left, Chagall walked over and looked at it. “Uh-huh,” he said, and returned to Jacob. He began working now with heavy black strokes on the third panel, deepening the tones of the red background in the vicinity of Jacob’s head, then brushing away the excess with his large flat brush.

When Chagall’s stained-glass windows for Jerusalem were being prepared for exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, it became apparent that it would not be possible to show them properly in the museum’s regular galleries. The space was not just right, and the lighting was far from ideal. As a result, it was suggested that a special pavilion, two hundred feet long, be set up in the gardens behind the museum to show off the windows as they should be seen. Some of the functionaries objected to the extra expense. Besides, they didn’t want to “set a precedent.”Malraux settled the issue. “How would we be setting a precedent?” he asked. “There’s only one Chagall.”I reminded Chagall of the incident. He laughed.

“I’ve never said a word to Malraux about the Messages Bibliques because I’ve been afraid he’d be carried away by the idea. And if the government got into it somehow, it might become a political issue. The newspapers and Match would start screaming about the tens of millions of government money going into such a project. So I say nothing.” He laughed again. “Did I ever tell you what Rouault said when Vollard commissioned me to illustrate the Bible, in 1930? At that time Tériade and Maurice Raynal directed the arts columns of the newspaper L’Intransigeant. Since everybody had an opinion on the project, they went around collecting them and were publishing them in their columns. When they asked Rouault his opinion he said, ‘Chagall’s going to do his dance in front of the Wailing Wall.’ Well, that’s Rouault, a great artist, maybe, but a pain in the neck. Vollard didn’t come to see me for a year after that. Finally I told him I needed the work in order to eat, and we got on with it.

“In our bodies there are good microbes and bad ones. The good ones fight with the bad and defend our bodies against them. It’s that way in life. There are people who are against you, jealous of you, who struggle by every means, sometimes beneath the surface, sometimes in the open. I’ve had lots of microbes like Rouault, and others. Those microbes can knock you flat if you don’t have the good microbes to go to your defense. Look at the Christ, the great genius, the great prophet. How many bad microbes tried to overpower Him! Not the poor Jews, but the Romans, the fascists of those days, who held the power. If the Christ was killed by the bad microbes, how should we expect to resist? That’s why I ask for nothing, why I work for nothing in all this. But the Christ asked for nothing, and still they killed Him.”

Charles Marq and Brigitte came into the atelier. Charles sat down at the Abraham lancet, and with the photograph of the maquette in his hand painted in several heavy black lines. I asked Brigitte what he was doing.

“They had to take out some of the leads in making the changes Chagall asked for. That changed the contour of Chagall’s composition. Charles is restoring the original line, based on the maquette.”

Charles finished his “restoration,” set down his brush, and joined Brigitte and me halfway back in the studio. “No other painter works like him,” he said. He pointed to “The Sacrifice.” “The color is all right now, but the light hasn’t been controlled. The glass is raw. You see the way he’s been working with grisaille on ‘Jacob Wrestling.’ That gives depth and feeling to the color by making gradations of tone. The colors come into harmony through the values he establishes by means of the grisaille. All those little details he adds, the way he weaves the elements of the composition together, the lightness or the heaviness of his line, the scratches and digs he gives to the grisaille — that’s what makes the glass come alive. You see that the painting he’s doing now runs the gamut from the most transparent gray to opaque black. That’s what controls the light. You’ve seen the way he has changed the whole character of the Jacob lancet — as far as he’s gone. The Abraham lancet will go through that same metamorphosis before he gets through with it.”

Brigitte left us and joined Chagall at the Jacob lancet. With the large brush she laid on a coat of grisaille in the point of the lancet, dulling down some of the lemon yellow and a slash of orange in the wings above the angel’s head. She set down the brush and came back to stand with her husband and me.

“You notice,” Charles said, “that the angel’s body is rose and Jacob is mostly blue. But the front of Jacob’s face — his nose, and so forth, in profile against the angel’s body — has the same rose color as the angel. I hesitated before putting in a lead there to make a diagonal slash that divides the blue from the rose right across Jacob’s profile, but Chagall’s color is like that on the maquette so I did it that way. Stained-glass craftsmen used to follow the drawing when they laid out their leads, but that puts the composition in a straitjacket. This way it breathes.”

Chagall stood back from the window and pointed to the angel’s thigh — white with a blue outline. “You have to leave an area like that empty.”he said, whether to himself or to Jacob, I wasn’t sure. He selected a small brush and painted in, with great deliberation, a very tiny half-moon shape on the knuckle of the middle finger of Jacob’s left hand. Charles Marq tried to choke back a chuckle. He grew red with the effort and turned toward me. Silently and simultaneously our lips formed the same word: “Inoui.” He walked out of the atelier. Brigitte moved closer to me. “It’s really thrilling to watch him work,” she said. I told her it seemed almost incredible that he could still give every ounce of himself to the work and find each touch so important. She nodded and made a variant of the gesture Chagall had made a little earlier to indicate that all this poured out of the very center of his being down into his fingers. “He’s really inhabited,” she whispered.

Did he hear us? Without turning around, he said, “It’s done with very little things. Like David and Goliath. David used just one stone — in the right spot.”

“Don’t you want to eat? It’s one o’clock,” Brigitte said. Chagall moved back and looked at the head of Jacob and the angel. “I didn’t think, this morning when I came in, that I could do anything with that,” he said. “But now I think it’s coming.”

“It will come,” Brigitte said.

Chagall nodded. “It will come.”

“He’s sweet, the angel,” Brigitte said.

“Like your child,” Chagall said. “I’m beginning to love him, too. And Jacob, he seems to me like my brother. Those poor little hands, and the head. It almost makes you cry, no? Like your boy, Benoît. I didn’t think I could bring off that profile, honestly I didn’t. And that bouquet — it’s not just sitting there behind him. It’s alive, sticking into his bottom. Well, maybe I have a right to eat after that, but I mustn’t stay too long at the table. Too much to do.”

DURING lunch we settled the affairs of Russia, China, India, Venus, Mars, and the moon. Chagall checked his watch against mine and decided it was 1:45. “All right, let’s get back to work,” he said.

“Why don’t you settle down now and take a little rest?” Brigitte suggested.

Chagall shook his head. “Work to be done. Let’s go.”

“No, no,” said Charles Marq. “You stay right here. There are still a few changes to be made in The Sacrifice,’ and there’s nothing for you to do just yet, so relax.”

Brigitte threw back the comforter on a day bed behind Chagall’s chair. “Why don’t you lie down here?” she said.

Chagall sighed. “Maybe. For a few minutes.” He stretched out on the bed. I could see he wasn’t really resting, though. He seemed to be listening. In a few minutes he was back on his feet. “I hear Michel downstairs. He must be bringing in the panels now,” he said. We followed him down to the atelier. Michel was fitting the reworked panels of “The Sacrifice” into the right-hand frame. When he had finished, Chagall picked up a longpointer and tapped an area in the foliage of the tree to the left of Abraham’s head.

“I want it more pale in here, Charles,” he said.

“But no,” Charles Marq said. “We changed that because you said it was too pale. That moves around just right now. I changed that whole area around for you.”

Chagall shook his head. “I’m not completely happy about it, all the same. It’s too stiff. It needs just another little piece in there.”

“Well,”said Charles Marq, “I could replace that blue above the tree by a warm reddish rose. That will bring it closer to the maquette. With a bit of silver-stain yellow.”

Chagall nodded. “All right. That’s enough for that. Now,” he said, pointing down to the form of Isaac in the bottom panel, “I want something warm along the side of his leg here.”

“I’ll put in a strip of yellow on neutral,” Charles Marq offered. “Will that make it right?”

“That’s what I’ll see,” Chagall said. “Now, here,” he said, tapping Isaac’s right arm with his pointer, “I’ll make you a present of this. I don’t need it. And this.”

Charles Marq groaned. “Oh, no. Not that.”

“Oh, yes,” said Chagall. “Get rid of it, you understand? And I want more yellow on the right side of Isaac’s face. And I want the blue of Abraham’s head continued so it will replace the darkblue shadow behind it.” He tapped the tree to the left of Abraham. “I want three spots of green — maybe four — in here.” He moved over to the right and studied the small group of figures above Abraham’s head: Christ carrying His cross and four or five other figures sketched in roughly in black. “I can’t see the Christ carrying His cross,” he said. He looked at the maquette. “It’s not readable. I want to see Him carrying His cross.”

Chagall reached up with his pointer and tapped the violent red area on the right side of the angel’s chest, in the point of the lancet. “This is good, but over here” — he tapped the left side — “it’s too dull. I want a more revolutionary red. Frankly revolutionary. And here, down by Abraham’s foot, you’ll put in a piece of the same green as up there. Now, have you got all that marked down in your head, Charles?” Charles assured him he had. Just to make sure, Chagall recapitulated rapidly each one of the changes.

“Perfect, perfect,” Charles Marq said. He climbed up on the ladder and tested a piece of red glass against the angel’s chest, then left the atelier. Michel removed the upper rectangular panel of “The Sacrifice” and then the point of “Jacob Wrestling.”

Chagall sat down. “Maybe I make them work too much,” he said, “but you have to know what you want, and when you do, then you have to see that you get it. Every orchestra needs a conductor. If I ask for the maximum, it’s because it’s really the minimum.”

Michel finished removing the panels. The stove, like Chagall, was burning high. “It’s too hot here,” Chagall said. “Can you calm down the stove a little bit, Michel?” Michel checked the draft, then went downstairs with the panels.

Chagall addressed himself to the upper rectangular panel of “Jacob Wrestling.”I saw him touching in tiny dots of black in the neutral-rose area to the left of the angel’s head. He then wove thin black lines into the left-central border that he had said earlier was too pale. The light had shifted now, and I could see the results of the work he had done this morning in the bouquet that was “sticking into Jacob’s bottom.” The flowers that earlier had glowed only dully seemed suddenly to have come to life. All around that part of the panel, light was pouring in through hundreds of tiny threadlike leafy patterns — the result of the pecking and scratching that had rattled the glass and scattered the clothespins. From palest blue to darkest purple, neutral rose to deepest red, they all sang together now, pulled into one chorus by the light, weaving its way through the flowers of Chagall’s grisaille.

Charles Marq and Brigitte returned from belowstairs and came over beside me. “It’s amazing,”Brigitte whispered, “how he knows just what is needed and he adds that and no more. It’s as if the glass had veins and has been growing.”

“Basically he’s not a naturalistic painter,” Charles Marq said. “Look at those arrow and wing motifs moving up into the point. That’s very Gothic, and yet it’s very much of our own times — a kind of bridge across the centuries.”

Chagall moved rapidly back and forth across the glass, through time and space, building his bridge.

WHEN Charles Marq left to go back to the street-level workshop, I went along with him. Michel had brought Chagall’s large framed maquette downstairs as a guide to the changes they were about to make and had set up in a frame on one of the benches the panel of “The Sacrifice" that contained the head of Abraham. Chagall had asked to have the deep-blue area behind Abraham’s head faded off into the paler blue to the left of it.

“That’s the wonderful thing about this plated glass,” Charles Marq said. “Very often, without changing a thing, simply by engraving the pieces that were too strong, you can tone down the color.” He turned to Michel and pointed to one of the pieces marked for change. “Here, though, you’ll have to cut a new piece from a G I’ll pick out, and here, another one.” He selected several rectangular glass samples, about three quarters of an inch wide and five inches long, each marked with the letter G and a different number. I asked him what the markings represented.

“The letter stands for color,” he said. “They’re just arbitrary symbols: G means blue; J, green; K, yellow; F, violet and purple. They don’t correspond to the initials of the colors themselves, except for R, red. The numbers represent the tonal gradations within the range of that color.” He handed two of the samples in front of him to Michel. Michel went over to the storage bins across the hall and returned with two pieces of a lighter blue. With a knife he pried away the edges of the leads that held the four offending pieces in place. Charles Marq removed them and passed the two pieces to be changed to Michel. Michel traced their outlines on a sheet of paper and cut out the paper forms. Using the paper cutouts as a guide, he cut new pieces of glass in the required tones.

Charles Marq picked up the other two pieces, the ones that were to be lightened through engraving. I followed him into a small sink room at the back of the ground floor. He turned on the water and put on a pair of very heavy rubber gloves that reached halfway to the elbow. He dipped a medium-sized paintbrush into a solution and scrubbed the glass, which he held with large wooden pincers under a constant flow of water. With his continued scrubbing the color paled slightly.

“This is hydrofluoric acid,” he said. “The glass is plated. That is, at the factory the basic color is dipped into a second tone of molten glass, which adheres to it. Then it’s blown and cut. That gives a basic color that varies in thickness from two to three millimeters, and, on top of that, a film of glass in another color that is no more than one tenth of a millimeter thick. That’s what I’m thinning down now with the acid.

“Most people think of a mechanical action when they hear the word ‘engraving,’ like the action of a drypoint or a burin on a copperplate. But engraving here is a chemical action, with the acid eating into that very thin strip of colored glass that is plated onto the main body of the glass. That method of combining two tones gives us the widest possible range of color nuance.”

I asked him how many different nuances of color they stocked. He thought for a minute. “Oh, I should think about four thousand,” he said. “But even with that great variety and all the expert craftsmanship that goes into the assembling of the window, when the glass is brought up to the studio, fresh, unpainted, the contrasts are sharp and sometimes brutal. The painter’s job is to make the transitions more subtle, to give depth and accents where they’re needed, to bring in the light so that it creates the image he visualized in the beginning, when he painted the maquettes. Chagall makes us change pieces sometimes three and four times, and the engraving I’m doing now is one way we have of coming closer to what he sees when the glass itself — even if we’ve changed it, like this, several times — doesn’t satisfy him. He makes us work, but, as you can see, he drives himself even harder than he does us.”

By now he had finished engraving the second piece. He took off the rubber gloves, wiped off the two pieces, and we returned with the glass to the front of the building, where Michel was waiting for us. Charles handed him the two pieces, and we went upstairs to the atelier. As we walked in, Chagall was working on the point of the Jacob lancet, near the tip of the angel’s wings. He stepped back. “Something’s wrong here,” he said. “Too many leads.” He pointed up at a form in orange that pierced through a patch of lemon yellow.

“I think if you dulled down some of those bright areas, that would take care of it,” Brigitte suggested. Chagall took his big brush, dipped into the paint, and washed a coat of grisaille over the trouble spot. He groaned. “Too many leads. It’s just too much,” he said. With a smaller brush he drew in several black lines on the left-hand side of the wings. He shook his head. “No matter how I struggle there are still too many leads here.” He began rubbing out some of his black lines. “Too many leads.”

“Those little points of color are too strong,” Charles Marq said. “They can’t stand up by themselves.”

“That’s right.”Brigitte said. “It’s too much.”

“Too many leads,”Chagall said. He pursued his path across the glass, getting farther and farther away from the orange form, digging into the grisaille with the wooden tip of his brush, then reversing it to add paint in an adjacent area, changing it for a larger one that spread the wash more fluidly; then, with the large dry brush, fanning out the color vigorously. The glass was rattling briskly, and another of the clothespins popped off onto the floor beside him. “Too many leads,” I heard him mutter.

When Charles Marq left us at the hotel at the end of the afternoon, he suggested we meet in the lobby at 8:30 the next morning rather than at 8:00, to give the light a chance to get with it. Chagall agreed.

As French provincial hotels go, the Lion d’Or in Reims puts up a rather chic front, but when we entered the lobby, we found it overrun with hunters and their dogs. The bar, facing us, was crowded. The restaurant, on our left, was not yet open for dinner. Chagall asked me if I was interested in dinner. I told him Brigitte had given us too good a tea; I had no more appetite.

“I don’t either,” he said. “I’m going upstairs, eat an apple, do some writing, and turn in.” I went out to pick up some paper and a book before the shops closed. In a fruit store around the corner from the hotel I came across a very promising bin of apples intriguingly labeled “Vinsapp.” I bought three of them. Back in my room, I ate one with some petit-beurre biscuits. It tasted just like any other winesap.

WHEN I got downstairs at 8:15 on Sunday morning, I found Chagall sitting in a club chair in the middle of the lobby, red-nosed and disconsolate. “Je suis grippé,” he managed to get out, between sniffs. “I woke up that way in the night, then fell back to sleep. When I woke up again, I looked at that damned watch, and it seemed to me it said seven o’clock. In Paris, that is. I got up, dressed, and came downstairs to get some tea. I thought that might help. There were hunters all over the lobby, with their dogs. Most of them were drunk and smelled bad. I saw the dining room was closed, and I asked the elevator man what time it was. ‘Four o’clock,’ he said. I went back upstairs, undressed, and went to bed. I slept a bit more, then got up and came down to the dining room for breakfast.” He looked at the magnificent Swiss watch, then shook his left arm reproachfully a few times. “Never needs winding,” he said disgustedly. He caught sight of Charles Marq in the Volkswagen in front of the hotel. “Well,” he said, “I guess it’s time.” We trailed out to the car, climbed in, and Charles Marq started off. From the rear seat I could hear fragments of a conversation that centered about some hunters and their dogs, all of whom smelled bad at four o’clock in the morning, crowded into a small elevator with a man whose wristwatch told the time, or didn’t tell it, in every major city in both hemispheres.

Up in the atelier the light was beginning to show through the high window. Chagall took off his shaggy German overcoat and his jacket and started to remove his vest. “You’d better keep that on,”Charles Marq said. Obediently, Chagall buttoned up the vest and put his checked lumber jacket on over it, sneezing and fumbling with the zipper. He went over to his painting table and fooled around with the brushes.

“Are you sure you feel like working today?” Charles Marq asked him. “You don’t want to go back to Paris?”

“Oh, no,” Chagall said. “Trains are always crowded on Sunday. Last week I went back on Sunday, and with all the weekend crowds returning to Paris, there were no seats. I stood in the door of a compartment . There was one man alone, and a couple with three children. Since the children were all small, I thought one of the parents might tell them to move a bit closer to make room for me. But no. Finally the man alone said he was going out to smoke, and wouldn’t I like to sit in his seat while he was gone. I did, but when he came back, I had to give up the seat, of course. Still not a move out of the family of five. They stayed in their seats, staring straight ahead, till the train stopped.”

Chagall picked up his brushes and sat down in front of the head of Jacob. He picked up the photograph of his maquette, set it on an easel beside him, and began to paint, slowly and quietly. I watched him for a few minutes, and then, when Charles Marq left the atelier, I followed him into another equally high-ceilinged atelier, flooded with light, just across the hall.

“This is our drafting room,” he explained. Two life-size cartoons for stained-glass windows in abstract patterns were hanging on the far wall. I asked him how Chagall had come to work in the Atelier Jacques Simon. He settled himself on a high stool in front of a drawing board.

“Well,” he said, “I had already done the windows in the large chapel on the south side of the nave at Metz with Jacques Villon, between 1955 and 1957, and with Bissiére had begun the windows above the doors on the north and south sides of the nave. At that moment, Robert Renard, chief architect of the Cathedral of Metz, had the idea of asking Chagall to do the two windows of the choir. If it hadn’t been for Renard, we’d still be at the level of Matisse’s window for his chapel in Vence or of Rouault’s at the Plateau d’Assy, both rather minor works. It was Renard who launched the painters into big ensembles in the great historical monuments. He told Chagall that it was Brigitte and I who had worked with Villon. Chagall had worked with another craftsman for the two small yellow and white windows he did for the baptistery of the Plateau d’Assy that light up his large ceramic of the Crossing of the Red Sea. He hadn’t been very satisfied with those, and after he made his first maquettes for the first window at Metz, he told Renard he wanted to see me and talk with me about the new job.

“I went to see him. We talked about the problems of stained glass in general and about its mission, especially from the point of view of light and the radiance of tones. He asked me many questions. We soon saw that our ideas were very close. He had made his maquettes with the freedom he would have brought to any gouache, but bearing in mind that instead of having a reflected light, it would be a light by transparency that diffuses the color, that makes the tones a hundred times more radiant than they would be in a painting. Then he made the two large maquettes, one of which is now in the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris and the other in the atelier across the hall from us.

“I had gone to see Chagall in Paris at the end of October, 1957. Up until then no one was in on the project except Chagall, Renard, myself, and Jacques Dupont, Inspecteur Général des Monuments Historiques, who was trained at the Louvre and is a specialist in sixteenth-century French drawings, a man with a very great knowledge of art and architecture. When it came time to present the maquettes to all the other people interested in the project — well, that’s a story all by itself. I’d better come back to that later.

“Anyway, for a long time Brigitte and I had been hearing echoes of the hostility of some of our confreres in this métier — the old guard of master craftsmen who didn’t like to see us branching out in a way that brought modern art into the cathedrals. Who are these two people, Charles Marq and Brigitte Simon, and what do they think they’re doing? They’re incapable of doing the job themselves, which is why they turn to painters for collaboration, and so on. That was the general refrain. But it’s not at all true. We had both, Brigitte and I, done many large and important windows, independently of any collaboration. What the old guard was really against was not us but the painters — the great painters we were working with. The maîres-verriers themselves, as a class, are often painters and engravers but generally of such mediocre and unimaginative character that they’re capable of little more than making a reasonable copy of some stylized and hackneyed image. People commissioned them to do stainedglass windows, and they turned out conventional jobs because it was their business to do so, not because they were creators or had anything original to say. They set themselves up as the jealous guardians of the secrets of the Middle Ages. But there are no secrets of the Middle Ages — not as far as stained glass is concerned, at any rate. Naturally, Brigitte and I had great fun letting some of the air out of their balloons.

“To get back to the acceptance of Chagall’s maquette: the chief architect, Robert Renard, convoked the commission to look at the maquettes. Ordinarily the designer would have come before the commission to present his work, but in view of the fact that in this case the designer was Chagall, Renard thought it more fitting that the commission should call on him. That was in April, 1958, when Chagall was still living on the Quai de Bourbon.

“First to arrive was an inspector for the Monuments Historiques, whose territory, so to speak, included the Cathedral of Metz. It was obvious that he had no idea of who or what Chagall was. For him, Chagall was just some painter who had been commissioned to do a window for the cathedral, and he had come to check up on his work and submit the customary official report to his superiors. He looked over the maquettes and said, ‘Why, this man doesn’t even know how to draw! Who ever had the idea of asking him to design a stained-glass window?’ This, mind you, right in front of Chagall. He simply didn’t know who Chagall was. It seems inconceivable, but the poor guy was just an example of the blindered, conscientious, but bird-brained little bureaucratic functionary who does what he’s told, minds his business, hates modern art in any form, and is proud of his prejudices. It’s like the old-line archaeologists in France: they hate art, and they know nothing about science. As long as they’re taking notes, writing on index cards, and filling up files, they’re in their element. Beyond that, expect nothing.

“If Chagall had been Picasso, this type might have known in general who he was, because there’s a kind of scandalous side to Picasso’s life and nature that manages to filter through to all levels of public attention. But a great artist like Chagall, who leads a quiet, exemplary life and whose goings-on don’t make newspaper headlines every other day, was simply some crazy modern artist who didn’t know how to draw. It was very clear to the inspector that the assignment of Chagall to do the Metz window was some kind of horrible administrative blunder, and he was washing his hands of the whole affair right on the spot, before somebody got the idea that he was responsible for it, somehow.

“So on he went, and the longer he talked, the whiter Chagall grew. He seemed almost to be shrinking back into the wall. You know Chagall well. You know how deeply he believes in what he does, but he has no vanity, puts on no side, strikes no pose of the Great Artist with all that. He was crushed. After the learned inspector had demonstrated to his own satisfaction that Chagall didn t know how to draw, he went on to attack the construction of his composition, and after that the color. Finally he finished his exposition and left, very pleased with himself.

“So, in the official view, that wasn’t stained glass. Nevertheless, at Jacques Dupont’s insistence, Chagall was authorized to make a sample lancet. So he made his Jeremiah lancet. When they saw it, they paid out enough rope so that we could complete the window — but just one window, no more. When the Jeremiah lancet was shown in the big Chagall retrospective of 1959 at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, Mrs. Myriam Freund, then president of Hadassah, and Joseph Neufeld, architect of the Hadassah Hebrew University Medical Center, saw it and commissioned Chagall to do the twelve windows for the synagogue of the Medical Center, outside Jerusalem.

“Chagall went to work immediately on his maquettes for those and finished them in December, 1959. Then he went back to work on the first Metz window. He finished that in May, and it was shown at the museum here in Reims that summer. In September, 1960, he began work on the Jerusalem windows, which I had been preparing for him all that year, and he finished them on the last day of April, 1961. He’s beginning to work here again now for the first time in a year and a half.

“The wonderful thing about Chagall’s stained glass is his sense of the universal religion. It would work as well for a synagogue or a Protestant church or a Catholic cathedral. It’s a personal imagery, not one dragged in from outside. It’s something that grows on his ground, an outward manifestation of his own nature.”

I ASKED Charles Marq if he could outline for me the routine they followed at the atelier between the time Chagall presented him with the finished large maquette and the time he presented Chagall with the assembled window. “The first thing we do,” he said, “is to photograph the maquette and blow it up to grandeur d’exécution. On that photograph I put tracing paper, and on the tracing paper I work out the placement of the leads, the construction, the design, the division of the color. On the place where each piece of glass is to go, I set down the tone that corresponds to the tone Chagall used in his maquette, as well as the annotations that refer to the engraving of the glass. When we were down in the shop making changes on Abraham’s head, you saw the symbols for color and value — G 202, for example, for one particular kind of blue. There are signs, also, for the engraving of the glass: ‘OO’ means fully; ‘O,’not quite completely; ‘minus’ means not quite so much; ‘plus’ means even less, and so on.

“Then the glass is cut in accordance with my annotations. Each operation is a specialized métier. There are good and bad cutters. For example, Michel, who worked with us yesterday, cut the whole series of Jerusalem windows. He’s very good. He understands color better than most young painters. He understands the difference between an ultramarine and a cobalt, between a cobalt and a cerulean. He understands how to make transitions; he feels it. Other cutters cut what is marked, and that’s that.

“When the window is assembled we place it on a glass table, which is lighted up from beneath so that each piece can be studied and worked on with the power of the light behind it. The engraver works on the pieces that call for engraving, in accordance with the indications I have given him. Once the pieces are back in place, the main lines of the composition are drawn on the glass. All this preparatory work takes about three weeks of specialized collaboration for each lancet. When Chagall arrives he finds the window ready for his work. For ‘The Sacrifice of Abraham,’ which you saw yesterday, he made the maquette four years ago, and yesterday he saw the result for the first time. He looks it over, studies the maquette. and asks for changes.

“When it is finally arranged to his satisfaction, he goes to work on it. He’s very demanding, as you’ve seen. The values have to be exact. Sometimes I have to tell him that what he wants isn’t possible, because if I changed everything he wanted me to, it could involve the whole mise en plomb. So when I tell him no, he realizes it just can’t be done or else we have to start again from scratch. Then he says OK.

“It wasn’t like that at first. We used to have some hot arguments, until he finally understood I was doing all I could to follow him. In the beginning we had one or two catastrophes by going too far. In painting, you can go too far and still not have a catastrophe. For example, one day when I visited him in Vence while I was preparing the Jerusalem windows, I asked him how things had gone with his painting that day. He said, ‘Bad. I spoiled everything.’ But it wasn’t a tragedy; it was only paint on canvas, and he just had to begin again. But in stained glass you can’t do that quite so easily. You have to throw it all in the rubbish barrel and come back in three or four months and start all over again.”

Sounds of activity floated in to us from across the hall. We went back into the main atelier. Chagall was working on the Sacrifice lancet. Jacques Simon and Madame Simon were standing in the center of the room studying the completed Jacob, on whose struggle the day was breaking more and more brightly. Brigitte was setting out tea things on the long table against the far wall.

“Look at that glass,” Jacques Simon said. “There’s a kind of miracle in all that. All those little marks you make that suddenly after a while come to life. I can’t figure out how you ever learned to do a thing like that.”

Chagall put down his brushes and came over toward us. “You can’t learn it,” he said. “It’s just a question of time. You have to do a lot of work over a long period of time. And then it comes.”

Jacques Simon continued to study the lancet. “I see what you mean,” he said. “If you tried to systematize it, it would lose all its freshness. Like true eloquence as against the cultivated variety. That’s the trouble with stained-glass craftsmen in general. They’ve learned their craft so carefully, there’s no place for the imagination.”

“Why don’t you send this window to Tokyo for the big retrospective they’re giving you in the spring?” Charles Marq suggested.

“I don’t know,” Chagall said. “It’s so big. Maybe it would kill everything else in the exhibition. Tell me, Charles, do you think this will be too high up in the cathedral? Will it really be visible?”

“Visible? You can be sure of that.”

Chagall looked unconvinced. “You ask Benoît,” Charles said. “I took him to Metz the other Sunday. He had never been there. We spent a quarter of an hour in front of your window.” He looked up at the heavy crossbeams about fifteen feet over our heads. “The bottom of your window starts about there,” he said.

“And that’s not really high up,” Jacques Simon said. “You have to consider the proportions of the cathedral.” He looked over at the Jacob lancet. “Oh, but that head. It’s simply wonderful. One would say it was Greek.”

“Jacob’s head?” Chagall asked.

“No, the angel’s.”

“You like that?”

“It’s classic,” said Jacques Simon.