On 25 March 2006, the photographer Bob Carlos Clarke checked himself out of the Priory Hospital in Barnes, southwest London, walked a short distance to a railway track, and jumped in front of a train. He was 55, and it was a terrible end to a complex life. But, as endings go, it was not an entirely surprising one.

Carlos Clarke was best known as a photographer of women in a state of undress, a subject that obsessed him long before he took up a camera. But his reputation - as "Britain's answer to Helmut Newton" - hints at only a fraction of his talent (or his potential talent), and suggests none of the turmoil that governed his career. How else to describe him? He was fastidious about control in his professional life but reckless in his private one. He wrestled continuously in the gulf between commerce and art. He was terrifically explosive company. He was his own worst enemy.

Why did he kill himself? There are several answers. He was depressed to be growing old while all his models always seemed to stay 21, not least because he felt he no longer had a chance with them. He detested the emergence of digital photography, which gave everyone the impression they were the next Cartier-Bresson. And he doubted the power of his own talents: the National Portrait Gallery failed to recognise him, but would hang a portrait by his 14-year-old daughter Scarlett as soon as he was dead.

And yet by popular standards less rigid than his own, Carlos Clarke was a success. He featured regularly in the photography magazines, where he offered provocative insights and was regarded as an innovator. He was a big star at the annual national photo expos, young photographers packing the lecture halls. He was in demand for calendars and advertising shoots, on which assignments he would be rude to the creative account directors and they would be pathetically grateful he even noticed them.

He established a body of work that was original, diverse, challenging and often beautiful. It was always striking: you couldn't walk past his pictures without emotion or reaction. It was not always easy to imagine his photographs hanging on your wall, for even the simple and seemingly placid ones - stones on a beach, a twisted fork and spoon - contained an erotic charge reminiscent of Robert Mapplethorpe's flowers. At their worst, his photographs could be a one-gag display of glossiness. But at their best they expressed an inner turmoil that reflected the authenticity of their maker. They were un-British, and as such they would always make waves.

I only met Bob Carlos Clarke twice, but he made a deep impression. The first time I met him he was taking photographs in a club, but it was daytime and he seemed uneasy, a shark out of water. The second time he was in his vast studio in Battersea, and he was the king - commanding the girls, cajoling his assistants, regimenting the louche lunchtime stories. Wrapped in this cocoon, you could believe there was no other photographer in the world who cared as much about his craft, or held such mastery over it. I thought he would be an interesting man to spend more time with, and I believed there would be plenty of opportunities.

Apparently, I made a minor impression on him. Sitting at Bar Italia in Soho in the early morning, feeling frayed from working late, he wrote of one of our encounters that I couldn't decide whether he was glamorous or sleazy. I'm still not sure; probably neither.

When he died I barely blinked. The BBC first reported his death as an accident, and the obituaries catalogued a man who was obsessed with imperfections and distrusted the world of professional fashion. They suggested he was crushed by not being taken seriously. Most of them got the facts right: born in Cork in 1950 to a fading aristocratic family, a repressed childhood, desperately unhappy schooling at Wellington, a stint as a journalist, a training at the London College of Printing and an MA at the Royal College of Art. He began photography as a way of picking up women, and his work became a hit with magazines and then an underground fetish scene. Years before Photoshop, he was fascinated by the possibilities of manipulation - not to perfect but to unnerve.

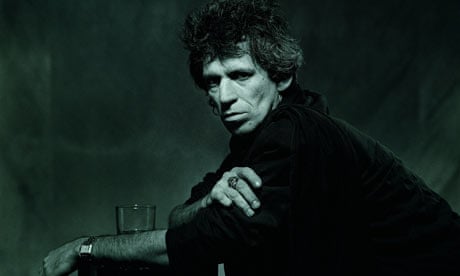

He was taken by the gothic and the futuristic, and he was fascinated by the organic enchantment of cemeteries. He photographed the famous - most startlingly Keith Richards, Rachel Weisz and the Amazonian models of the 1990s - but his best work includes a documentary study of hormonal teenagers at a ball and the found objects, mostly cutlery, he discovered washed up on the banks of the Thames. His biggest commercial success came with his friend Marco Pierre White. His study of Harveys' kitchen in the late-1980s focussed not on the dishes but on the cleavers and sweat that created them, setting the tone for the hard-living tormented celebrity chef and helping the book White Heat to the bestsellers.

And that would have been enough of Bob Carlos Clarke for me had I not had a fortunate professional encounter with his widow. I had embarked on a book about Ghislain Pascal, an agent and manager whose celebrity clients appeared often in OK! and cookery programmes. I thought spending a year with Ghislain and his people would reveal some interesting things about the star-making machinery, but I was wrong; it was as boring as he had warned me it would be - not least because his most exciting client, Bob Carlos Clarke, had died a few months before. And then I met Lindsey Carlos Clarke, Bob's widow, and the focus of my project changed. She was sorting through his archive in a rented lock-up at the World's End section of the King's Road, and she was everything Ghislain had told me she would be: alluring, funny, self-effacing and relentlessly forthright.

As she pulled boxes of his early work from the shelves, she told me of a life of such extreme peaks and troughs that I began to think she was quoting dialogue from a film. (The props were unusual, too: objects Carlos Clarke had made from driftwood found near his beach house in Bracklesham Bay, on the Sussex cost, including a crown; items that appeared in some of his photographs, such as an iron with a knife attached.)

"I always imagined there was a big, dark mess in his head to do with his childhood that he never came to terms with," Lindsey Carlos Clarke began. "But it was probably even worse than I expected. I mean, lots of people get sent away to school. Bob hated every moment of, and everything about it. He wrote endlessly tear-stained letters home: 'Get me out of here, this is so awful.'

"His mother, Myra, didn't want Bob to be sent away to school. In fact, she thought it was the most terrible thing. And then she had Andrew, who was eight years younger than Bob. So Bob went away to school, gets home and finds somebody in his nest. He never got over it, never. He used to do terrible things to Andrew - terrible, terrible torturous things. You know, nail him into a box and roll him down a cliff. Wished he was dead."

Lindsey Carlos Clarke had a specific reason to be at the archive that afternoon. An editor from Phaidon was coming to discuss the possibility of putting together a career retrospective. So everything was coming down from the shelves to be spread on a table, and with it came the stories of the photos and the character of their creator.

It was soon clear to me that Lindsey would answer questions about almost anything, no matter how intimate. If you were bold enough to ask, she would be brave enough to tell you. I began to meet her regularly, at her home and her favoured Italian restaurant, Frantoio, in the King's Road, and our conversations would turn into confessionals as soon as we sat down. Of course, the obvious thing one wonders about a photographer who spends a lot of time with naked women is how close he gets to them.

"I said to him once, not long after moving into this [current, Chelsea] house, 'You can have your girls in your studio but don't you ever, ever bring one of them back here.' The beach house was supposed to be pure as well, but that didn't last long... It was about secrecy. He said to me, 'I don't enjoy sex unless it's secret.'

"I told him, 'I want to change the shape of how we operate.' Loads of people change their lives. He said to me, 'But I'm not a drunk, and I'm not violent and I don't take drugs...' I said, 'Well, what about the addiction to other people? To the degree where you practically sleep outside their front door and endlessly surround them with poems and presents?' I think he was amoral - I don't think he understood. Everything had to be a risk."

Lindsey was his second wife. He had once been married to Sue Frame, a girl he met when he first picked up a camera at college in Worthing in his late teens. Frame had since remarried and moved to South Africa, but she came over from time to time to deal with family matters, and when I met her it seemed to me that her memories of her first husband were fused with regret, censure, disillusion and a faintly obsessive love.

"I don't know, he just couldn't keep himself zipped up. And yet he used to say to me, 'I will kill you first before you leave me.'" They had been married for two years before she became aware that he was having an affair with Lindsey. Frame believes that she had outgrown her usefulness, and that Bob saw in Lindsey - a model with great contacts - not only a soulmate but also someone who would boost his career.

They never met again after their divorce. "I just thought I've got to make a clean break because if I don't I won't stand a chance of rehabilitating myself. I was in a shocking state when he left me; I'd had my heart torn out. He left an indelible mark on me and I have carried it through the years. I used to fantasise sometimes about meeting Bob again and I just wish we could lay the bad ghosts to rest.

"He had this BSA 650 bike, and he said that if he ever thought he was getting too old he would just ride it off a roof one day. He didn't just say that once. He kept repeating it.

"For nine years I was his muse and I was his model and I went through all the rough years with him, when we didn't have money... Look, whoever he was with, he would still have gone on to be the great photographer that he was, but I believe I played a big part in it. He used to say to me - this was one of the mean things he'd say - he'd say, 'Oh God, it's such a pity you don't have bigger boobs and longer legs. I could have made a fortune out of you.' You bastard."

Not long afterwards I met Geraldine Leale, another of the women he was seeing while he was still seeing Sue. "With Bob it was never just going to be just a case of taking some nice pictures," she told me. "It had to be an obsession. I learned that very quickly. We had a bit of a fling that lasted 10 days or two weeks, quite full-on. I was living with somebody else at the time, and I thought, 'Bob's amazing, but he's barking mad.' It was a very needy energy. He knew that I liked reading the Beano, so he used to get a copy of the Beano and leave it on my doorstep with a little bag of chocolate money. Terribly sweet, but at the same time he wanted your undivided attention. I could see this deep distress in him, again that neediness. It was that vulnerability that endeared him to me, the fact he was always battling himself."

Leale told me that Bob wasn't her kind of lover. "He was too nervous. He was always trying to pit himself against somebody else, pit himself against Mick Jagger, for God's sake. Bob just couldn't relax. Having sex with Bob was never an act of love. It always felt as if you were this thing on the petri dish, being observed in some way, and all your reactions carefully tabulated to be thrown back at you a long time later. Bob loved being the cuckoo in somebody else's nest. He loved the idea that he could creep into my flat or anyone else's flat when the husband or boyfriend was out. For anyone to maintain that type of chicanery takes a great amount of effort. And it spiralled; it got worse as he got older. It wasn't just the women in his life - it was the persona of his life, and that had to be fed and watered."

"Bob had that wild side to him," one of his oldest friends, Sam Chesterton, told me (there were far fewer male friends than women). "But he was partly also a very old man. He liked everything just so. His eggs and bacon and whatever - it had to be done just his way. He also had his snobbish side where he revelled in his ancestry. Being a gentleman was very important to him."

The more people I spoke to about Carlos Clarke's work, the more it became clear how much he struggled between his great early passions and claim to fame - taking erotic photographs of beautiful women and the desire to be regarded as a serious artist among critics and collectors. One of his most astute admirers is Philippe Garner, a leading figure in the London photographic scene for three decades and the international head of photography at Christie's, and when they first met he saw in Carlos Clarke not only an original eye, but also a self-destructive quality.

"Partly what intrigued me about the pictures," Garner observed as he looked through one of Carlos Clarke's early books, "is whether he is photographing what he desires or photographing what he fears, and I suspect the answer is both. The power of sexuality is terrifying, and photographing it is a way of subjugating it. It's not that he wants to - it goes beyond the kind of corniness of fetishism, sadism. There is such a kind of strength of lust and passion for these bodies, for these curves, for this mythology of women who are on the edges of being women and goddesses. Curiously, even the way he renders skin, it's not skin as we know it in regular life, neither the colour or the perfection or the sense of it. So there is just a kind of relentless fixation with women who are bursting with a kind of implied or evident sexuality.

"But I can't believe that he could get to the age of 50 and still be predicated on adolescent lust, because I think one's nature changes, it evolves. It's banal to say so, but to many people who may come to the pictures for the first time, God, they're sexy pictures! Well, yes, but keep looking, other things will emerge."

It would be too easy to examine Carlos Clarke's work (the many photos in graveyards, the dark preoccupation with unattainable desires expressed in his portraits of women) and classify his latter years as a chronicle of a death foretold. To diagnose him bipolar may be equally unhelpful. His black periods were always outnumbered by his dramatic bursts of creative energy and new obsessions - his beach house, a new model - although they failed to sustain him for long.

Towards the end of his life, Carlos Clarke's vision of success seemed as far from realisation as it had ever been. He held bold new shows in London and Madrid at the end of 2005, but he seemed to take little pleasure from them. His doubts about his work strengthened, and his insecurities were expressed in erratic behaviour and growing paranoia. He became convinced he would be sued for failing to gain clearance to use his models' images, and he was distraught that Lindsey had threatened to leave him. "The fact of the matter was," she told me, "he was living in the basement. All I said to him was, 'I can't live like this.' And he just said, 'Don't bully me.' I could never get any communication... I said to him, 'Bob, I cannot go to my grave like this.'"

Like this, meaning what exactly?

"Unloved, unfucked, unspoken to, un... just robotic. I said to him, 'What do I do in your life that you couldn't pay somebody to do?' He said, 'Oh, don't be ridiculous. People our age don't have sex.' I looked at him and I said, 'That's not quite what I mean.' I found it very difficult to have a conversation with him on anything at all."

His one constant love, daughter Scarlett, wasn't enough to keep him seeking a way out.

"In January he just started to behave very oddly. I used to come down in the morning and take him a cup of tea and he'd already be up and dressed and sitting absolutely rigid on the bed, almost hyperventilating, and saying, 'I can't go on like this.' He'd say, 'I can't sleep, I can't eat, I can't breathe. I think I'm going to do something terrible.' I knew exactly what he meant, and I'd say, 'Well, shall we not do that today, shall we do something else?'

"I started to come down quite early in the morning and find the front door here open, and I didn't know where he was. I would remember things he said in the past, like he would ask, 'How fast would I have to drive my van into this wall in order to kill myself?' I'd be in my pyjamas, and I'd be racing round these streets thinking, 'Where are you? Where are you?' I'd see the van and see him sitting in it and I'd tap on the window and he'd look at me absolutely like he didn't know who I was."

Lindsey and his doctor persuaded Bob to go to the Priory for psychiatric care. After a fortnight, there were signs of improvement. "They said to me he was responding to treatment, and he was going to be all right," she remembers. She hoped to get him working again as soon as possible in a new studio. "And then it was the last Friday night. I took him some food in, and I said goodbye to him. There's this corridor where you walk down to this crossover point where the rooms are. I remember standing at the end of it and looking back and seeing him standing there, and I remember he said goodbye to me and I just had that very odd feeling: I don't think he looks much better to me.

"And Saturday morning came and I got some lunch together and picked Scarlett up from Clapham [their daughter, then 14, back from boarding school]. It was about two o'clock and the doorbell went and there were three policemen on the doorstep and I immediately thought, 'Oh my God, I've been caught, haven't I, putting on lipstick in the camera. Oh God, on the mobile.' All the things we do in the car. Absolutely thinking it's me. There were two men and a woman and they stood there for quite some time. Then she said, 'What relation are you to Robert Carlos Clarke?' and I knew immediately."

How should we regard him today? As a dispiriting mass of contradictions. Most of those

I talked to recalled a thrilling companion, the most alive man they had met. Others saw a soul in turmoil, tortured by his work and his standing, dedicated to betraying those who loved him. He once wrote that he believed a young death was imperative for his reputation. "If you want to qualify as a legend," he wrote, "get famous young, die tragically and dramatically, and never underestimate the importance of your iconic photographs."

Philippe Garner believes that Carlos Clarke deserves a significant place in the annals of British photography. "In many respects, Bob's work satisfies many criteria for being a highly marketable product. It's high, high quality, sufficiently rare, there's a finite amount, many of the prints are unique. It is quite tough, but a lot of it just manages to be about the right side of the line in a marketplace which is actually increasingly broad-minded. And now he's dead, and we know there's an extraordinary story around him, so I think all the ingredients are in place for it to become something which is really collected and sought after."

Three years after his death, Lindsey Carlos Clarke says the pain has not subsided; if anything it is worse. Earlier this month she was back at the archive selecting photos for his first retrospective. There was one abiding emotion.

"Anger. Anger like you can't believe. I sort of think everybody failed him, we all failed him somehow. And then this terrible empty feeling of sadness and remorse and a feeling of how vulnerable he was. That's why I protected him, because I knew I was stronger than he was, always. I'll never love anyone like I loved him. I think there's a piece of me that's gone, that doesn't exist. It's still a jolt. Sometimes I wake up in the morning and I think, 'Oh what a lovely day,' and I look out and think, 'Oh no, it isn't a lovely day at all...'"

Extracted from Exposure: The Unusual Life and Violent Death of Bob Carlos Clarke by Simon Garfield, published by Ebury Press on 14 May at £18.99. To order a copy for £17.99 with free UK p&p go to observer.co.uk/bookshop or call 0330 333 6847.