Call it a myth, a legend, nostalgia for the good old days, Norman Rockwell, the 78 year-old American artist whose work has been described as a popular history of the United States in the twentieth century, is one of the year’s most sought after artistic properties. His paintings, once scorned by the art world, are being exhibited in one-man shows at such prestigious museums as the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, and on the rare occasion when they are sold bring $30,000. A Rockwell painting of 1927 was revived for a Newsweek cover, and an exceedingly expensive Rockwell album is selling like hot cakes. The book Norman Rockwell, Artist and Illustrator includes all of Rockwell’s covers for the Saturday Evening Post and was sold out in its first two months grossing $2.5 millions at the initial offering price of $45. At $60 a copy sales have almost reached $10 millions – more than the hardcover and paperback gross of Love Story.

Exactly what has made Norman Rockwell so successful? Thomas Buechner, director of the Brooklyn Museum, who once described Rockwell as the most thoroughly American of all artists, had this to say: “His work evokes a response which in terms of numbers of people is greater than that of any artist that ever lived. When the last half century is explored by the future, a few paintings will continue to communicate with the same immediacy and veracity they have today. I believe that Mr Rockwell’s will be among them.”

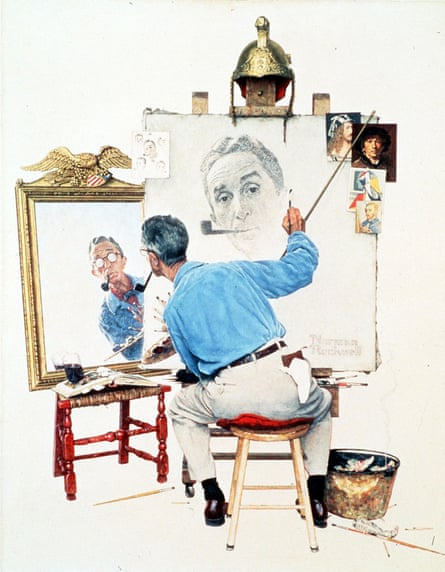

Rockwell himself is an extremely modest man. Some years back he said “I call myself an illustrator but I am not an illustrator. Instead I paint story-telling pictures which are quite popular but unfashionable.”

For more than half a century the art world sneered at Rockwell’s sentimental, realistic paintings with their total fidelity to nature. Today he is being acclaimed not only as a man who held a mirror to American social history in this century but as one of the country’s greatest genre painters. A critic wrote: “He has taught a generation of Americans to see. They look about them and see, almost everywhere they look, what Norman Rockwell sees – the tomboy with the black eye in the doctor’s waiting room, the father discussing the Facts of Life with his son, the youth in the dining car on his first solo flight from home. You might say that Mr Rockwell’s special triumph is in the conviction his countrymen share that this mythical world he evokes actually exists.”

Rockwell’s paintings are as revealing in their omissions as in their inclusions: no hippies, no slums, no Korea or Vietnam. Lots of freckle faced children, mongrel pups, first loves, baseball and Presidential campaigns.

Born in New York, Rockwell was successful from the start. “My ability was just something I had like a bag of lemon drops.” When he was 17, he illustrated his first book and when he was 21, did a cover for America’s most popular magazine, the Saturday Evening Post. Forty years later he had produced 317 covers – each printed an average of four million times. Some were amusing, some joyful, others evoked memories, inspired, exhilarated. But all reflected the American dream.

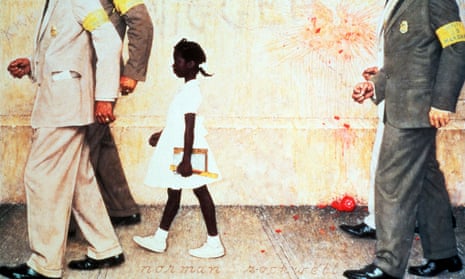

Asked how he could paint America for so many years with no black men in his pictures, he lit a pipe and took a long draw. “Years ago, a magazine editor told me never to paint Negroes in any position except servants.”

But eventually when Americans had begun to examine their own conscience, he did have a black period. Two paintings in the early sixties show three dying civil rights workers in Mississippi and a small black girl being escorted to school by a burly US Marshall in Little Rock. “I was doing the racial thing for a while,” Rockwell says, “but that’s for the birds now – nobody would buy it.”

This is an edited article. Click here for full version.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion