Magazines tend to starve for love nowadays. But not all. One exception may be Playgirl, a title that relaunches this week, featuring a cast of diverse and diversely focused writers and photographers orientated on the lives of women.

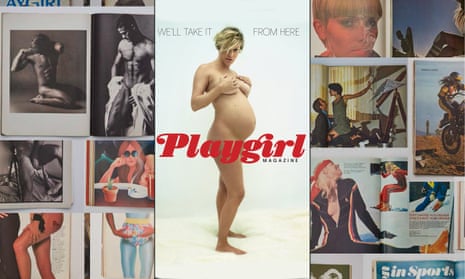

It’s an unusual moment to launch a magazine, especially a print-only title. Unusual, too, to relaunch a magazine that briefly – around 1973 – mirrored its recherché moment under the subheading “Entertainment for women”. The new incarnation comes with the declaration: “We’ll take it from here”.

Playgirl, a notionally feminist title, simply countered Playboy’s Norman Mailer with Maya Angelou, Hunter S Thompson with Margaret Atwood, and matched its male centrefolds – pose for pose, Speedos (or less) for lingerie (or less) – with those of Playboy’s women.

“They’re really fabulous in so many ways, but they do look like a man’s idea of what a feminist publication would be,” Playgirl’s editor-in-chief, Skye Parrott, told the Observer. “Everything they did in Playboy, they did in Playgirl. It was interesting for a couple of years, then it was sold and resold, and it became what I thought of as a gay porn magazine.”

Indeed, the magazine’s opening essay, by writer T Cole Rachel, talks about the irony of a magazine that was intended for women being co-opted by men – even if those men were gay.

Parrott, a photographer and mother of three, is the former editor of Dossier, a New York-based magazine that in a co-operative and hip fashion championed social and racial diversity, the female gaze, and other aspects of progressive 2020 enlightenment, well ahead of the media industry, and perhaps society at large.

Dossier played a part in launching the careers of Cass Bird, Harley Weir, Zoë Ghertner and Bibi Borthwick, who have come to define the post-male-gaze aesthetic in fashion photography. Women wrote about losing their virginity; Dossier talked to the Iranian artist Shirin Neshat; Parrott, who once ran art photographer Nan Goldin’s studio, went to photograph fashion in Jacmel, on Haiti’s southern coast.

Playgirl, almost by definition, is an oddity at this juncture when the publishing business is in a precarious state. It’s best seen as a creative enterprise, hopefully to be repeated, headed by Parrott and executed over two years with the backing of neophyte publisher Jack Lindley Kuhns. It carries a lightness of touch, refreshing without being oblivious, and redolent of a surrendered but not abandoned life as much else teeters.

“The world we all live in was created by men, and so it is centred around male values. I wanted to create a magazine that could offer an alternate point of view – the feminine,” Parrott says. “Who creates images is important, and the politics of gender has been woven through my work. I thought deeply about what a feminist publication could be, what it could achieve, what stories it should tell and how they’re told. I hope it’s now a woman’s idea of what a feminist publication can be, what feminist values are, and how a magazine can elevate them.”

For the relaunch cover, the actress Chloë Sevigny, 45 and nine months pregnant, posed naked for her friend Mario Sorrenti, a visitor from the male spectrum. “The picture is antithetical to the male gaze. Her expression is tentative, the picture’s power comes from her pregnant body. It’s a hyper-feminine thing: not a sexualised body, but a human body,” says Parrott.

Elsewhere, the magazine includes the in-demand black writer Carvell Wallace, who writes on the slow fall of the patriarchy and how women and men will be well shot of it; an essay on the relief of surrender (in the spiritual sense); models that are challenging outdated ideals of beauty; and the jewellery designer Pamela Love on the exhaustion and mental health challenges of making the exterior match the interior – “a darkness brought me to my knees, but it also brought me to a place where I was able to make choices”.

And it talks to indigenous female artisans of the organisation Kiptik in Chiapas, Mexico, connecting them to fashion retailers looking to weave sustainability into design and manufacturing. “Rather than suggesting that the path for successful women is in the male world, we wanted to show that traditional female crafts can be turned into a viable path for women to sustain themselves,” Parrott says.

There are personal essays on the power of desire, the fashion for radical modesty, and a focus on community building, with entries by the teenage climate justice activist Elsa Mengistu and Chanel Miller, the author of Know My Name, a memoir that changed the cultural conversation around consent, assault and rape on college campus, plus the work of music executive turned refugee campaigner Josie Naughton.

The writer Alicia Garza, co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, writes on her life as a racial justice activist: “I hate the word ‘woke’. It’s as if there’s some level of enlightenment that you get to, and then your work is over. It becomes a weird clique, like ‘I know everything’, and then other people are outcasts and pariahs if they don’t use the right lingo.”

But Playgirl couldn’t function as Playgirl without addressing nudity. The notion, Parrott says, was to approach it from the perspective of vulnerability. Harley Weir’s centrefold of a sitting black figure without overt muscularity was selected to get that point across. “For a man, nudity means sex; for a woman, it means you’re exposed,” says Parrott. “It’s a different lens and, hopefully, a different perspective.”

The portrait is adjacent to a double-page spread of two erect penises pointing at each other. “It’s really funny, but it’s got some subversion to it,” Parrott says. “Pictures of naked men are inherently subversive in and of themselves.”

Playgirl’s subtle overlap of the personal and the political points a way beyond the present architecture. It owes much to Parrott’s previous work at Dossier and her experience as a photographer and managing editor at Self Service magazine in Paris. Parrott noticed that as she moved along, many women in her field fell away, or gave up something – a family, for instance – in order to progress. “It worried me and it didn’t sit right. Once I had created a space – a magazine – for people whose work I believed in, a lot of them turned out to be women.”

Dossier, she recalls, was designed as “an inclusive space with lots of different points of view and different people, like New York itself. Body-inclusivity and diversity were a given. At the time, the conversation about how women and diverse voices weren’t being afforded the same opportunities wasn’t as loud as it is today.” For Playgirl, there were companion thoughts, one of which was voiced by the writer Ruth Whippman in the New York Times last year under the headline: “Enough leaning in. Let’s tell men to lean out.”

The magazine, which hits US newstands this week, arrives as the pandemic has exposed and amplified a range of social fractures and injustices. While women have been disproportionately affected, it’s been a leveller, in certain respects, with men now also stuck at home, on Zoom calls, with children running under their feet.

In some ways, Parrott says, the chance for a reset has been a gift. “The world right now requires a certain vulnerability and flexibility, and I wonder if women have had more practice living in that space because we’ve been required and allowed to. The question is, rather than demanding women lean in and act more like men, is there an opportunity to take more feminine concepts and offer them to the world?”