Cathaya argyrophylla - International Dendrology Society

Cathaya argyrophylla - International Dendrology Society

Cathaya argyrophylla - International Dendrology Society

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TREES30m, an example being a tree at Dayao Shan, Guangxi, which was that heightmore than 20 years ago, at which time the highest at Huaping, Guangxi at21.1m (Mao 1989), was possibly in reality over 30m high, as Tang Xiyang(1987) mentioned a Huaping tree at Wujiawan as “the largest Cathay silver firin the world”. <strong>Cathaya</strong> trees were listed having trunks of 79.2cm/83cm d.b.h.at Dayao Shan/Huaping (Mao 1989), the Dayao Shan one being measured at86.9cm d.b.h. in 2000, substantially more than noted in the literature. Whileit would be interesting to know, I have been unable to find out the presentdimensions of these trees, or those in the other nature reserves where the treesare known to occur (see map/chart pp. 156/7, Callaghan 2007a). A 24m tree inHunan Province has been dated at 390 years old.Another interesting fact often confused in the literature is the time takenfor the seed cones of <strong>Cathaya</strong> <strong>argyrophylla</strong> to mature (from pollination). This isoften erroneously stated as one year (“maturing in first year” – Flora of China,Fu et al. 1999) or as a single (growing) season. Inexplicably, the lead authorfor Pinaceae in Flora of China, Fu Li-kuo, had earlier stated “cones maturein the following year”, ie. second year (Fu et al. 1992). Some authors statethat in Pinaceae, of which family <strong>Cathaya</strong> is a member, only Pinus and Cedrushave cones maturing in two years, with a few species of Pinus maturing inthree years.The reality for monotypic <strong>Cathaya</strong> is that the female strobili (see photo, page76, Callaghan 2009) formed from pre-existing initials in the axils of a few of thelower leaves of the newly expanding shoots, open and are pollinated (mid–)late April to early May (Huang et al. 1985 – see photo of receptive flowers,page 102), after which the flowers close. Fertilization takes place in the lastten days of June the following year (Wang & Chen 1974). After fertilizationthe 13 - 16 ovuliferous scales rapidly expand to cover the bracts (see photo,page 103) and the female cones enlarge to their mature size of 3 - 5cm by1.5 - 2.5(- 3)cm wide by October, at which time the scales open to release themature seeds of the next generation. Hence the cones of <strong>Cathaya</strong> mature in18 months spread over two calendar years.The error concerning maturation of the cones has been perpetuated fromthe statement by the original authors Chun & Kuang (1962) 2 and repeatedin Cheng, Fu & Chen (1978), that “cones mature that same year”, and as aconsequence by many recent authors outside of, and some within, China. Wang(1990) mentions the original error by Chun & Kuang and confirms that “silverfir fruits never ripen in the same year”.Incidentally, the TV documentary Forest China mentions the interestingfinding that “a germ cell of a silver fir takes 31 months to grow into a matureseed.” (i.e. from the inception of a germ cell as an initial in the meristemthrough to a seed maturing, or 13 + 18 = 31 months). [see Endnote 3 concerningmale cones].I should note the occurrence of rare hermaphroditic flowers of <strong>Cathaya</strong>97YEARBOOK 2011

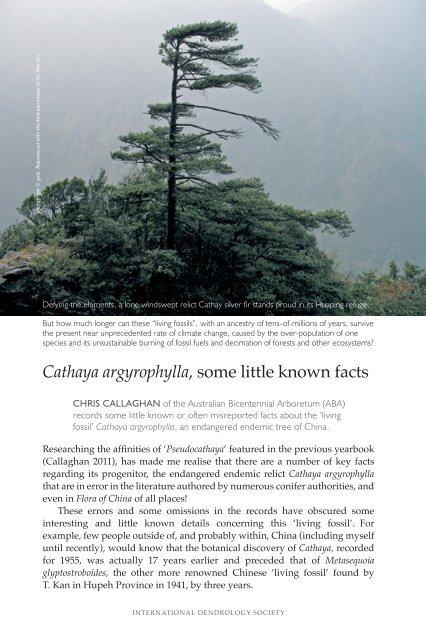

CATHAYA ARGYROPHYLLA98photograph © cnh(pe). Reproduced with the kind permission of Wang Yin-zheng; inset photograph © NEFI. Reproduced with the kind permission of Y. C. Yang’s familyThe undated, first ever collected specimen of <strong>Cathaya</strong> (C. nanchuanensis Chun et Kuang), Y. C. Yang’s3163 from Jinfu Shan, “Golden Buddha Mountain”, Nanchuan county in then S. E. Szechuan. Label inlower right-hand corner is the opinion by Cheng Wan-chun and Fu Li-kuo (names in Chinese) on1959-8-25 that <strong>Cathaya</strong> nanchuanensis is synonymous with <strong>Cathaya</strong> <strong>argyrophylla</strong>.Inset, Yang Yen-chin, who at 25 years-of-age discovered <strong>Cathaya</strong>, the “pearl of the forest”, in 1938,after which it slipped off the radar for another 17 years until rediscovered at Huaping, Guangxi in 1955.INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY

TREESphotograph and inset photograph © gxib. Reproduced with the kind permission of Xu Wei-bin99Isotype number 00198 of <strong>Cathaya</strong> <strong>argyrophylla</strong> Chun et Kuang collected at Wujiawan, Kwong FukEstate, southern slopes of Hongya Shan, Lungsheng country, Kwangsi, 16 May 1955. [the holotypeat IBSC was not made available for this article]Inset, Prof. Zhong Ji-xin, leader of the Kwangfu-Linchu Expedition whose members Deng Xian-fuand Li Zhi-you discovered the tree from which the type specimens were collected.YEARBOOK 2011

CATHAYA ARGYROPHYLLA100mentioned by Chun & Kuang (1962) and Zhang (2011), a feature I wasunaware of when writing about “Pseudocathaya” (Callaghan 2011). I can revealhere though that yet-to-be published ‘Pseudocathaya cyanescens’ is no ordinary<strong>Cathaya</strong>, having unique features that set it apart from any other living conifer!Finally, I’d like to say something about the much debated conservationstatus of <strong>Cathaya</strong> <strong>argyrophylla</strong>. Nothing I have become aware of since I advisedfive years ago (Callaghan 2007) that “perhaps the threatened status of <strong>Cathaya</strong><strong>argyrophylla</strong> should be reviewed, and possibly revised upwards?” has alteredmy suggestion. In fact the evidence presented here would tend to reinforce theneed for a review of its current status as ‘Lower Risk, Conservation Dependent.Version 2.3’ of 1994 (IUCN 2011).The comparison I made in the 2006 article of c. 5400 Metasequoiaglyptostroboides trees occurring in the wild compared to less than 4000 treesof <strong>Cathaya</strong> <strong>argyrophylla</strong> was without the knowledge that the majority of theMetasequoia were by then seed bearing individuals, many reaching maturitysince H. H. Hu (1948) put their numbers at no more than 1,000 large and smalltrees. A 2001 count put Metasequoia numbers at 5750 large protected wild trees.One forestry station at Metasequoia Valley cultivated and distributed 445million seedlings and 160 million cuttings of Metasequoia between 1979 - 2001(Ma et al. 2004), a large percentage of the cuttings presumably replicating thewild genotypes (virtually impossible for <strong>Cathaya</strong> with its negligible strikerate! – Huang et al. 1985, Fu 1992).The above contrasts with the situation for <strong>Cathaya</strong>, where at the time ofa 1989 census of these trees (Mao 1989), I have calculated there to have beenbetween 900 to 1000 mature individuals existing out of a total of 3266 wildtrees. Regarding the remaining c. 2266 - 2366 seedlings and saplings, it isinteresting to note that Tang Xizang (1987) mentioned that “in HuapingReserve” (Guangxi) “one still sees seedlings and saplings, but in Sichuan,Hunan or Guizhou provinces one sees few seedlings or saplings. Without eventhe risk of human damage, these precious plants face the danger of extinction.”Since then however, the number of <strong>Cathaya</strong> <strong>argyrophylla</strong> seedlings under20cm height found by surveys at Huaping, where Tang mentioned they weremost prevalent, have plunged from 903 in 1979 when they accounted foralmost 87% of the total 1040 <strong>Cathaya</strong> in the reserve (Mao 1989), to 97 in 2004,with only 17 being found there in 2010! The parent tree numbers over this31 year period have increased from 70 to 71 mother trees (Zhang 2011), butare barely reproducing. During an authorized visit to the reserve in 2009, myarboretum colleague S. K. Png and I saw no seedling silver firs during our timethere. The figures show that of the 69 saplings between 20cm and 5m countedin the 1979 census, plus the 903 seedlings, most have died, since allowing forexpected mortalities due to reasons 8 - 13 listed below, both categories wouldhave contributed by 2010 to a greater increase in the original total of 70 mothertrees [classified as trees above 5 metres or c. 18 years of age]. Hence as theINTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY

TREESmother trees die out over time, they are being replaced by only three or fourtrees in a century, which is not sufficient to maintain the long-term viability ofthe population at Huaping. Allowing for a corresponding decline in <strong>Cathaya</strong>numbers at the other reserves where little or no recruitment is taking place,could mean that this “giant panda of the plant kingdom” as it is dubbed byChinese botanists, is declining significantly in numbers in the wild whileits namesake, the giant panda of the animal kingdom is increasing [www.en.wikipedia.org for panda, accessed 3 March, 2012].Tang’s prediction above appears to be moving closer to reality and theplant’s survival may be in a precarious state as older trees die and are notreplaced. The lack of recruitment is due to a combination of the followingadverse factors reported by Zhang (2011) and others:1. Most trees have insufficient male flowers for adequate pollination.2. The flowering season in April coincides with the rainy season, playinghavoc with wind-borne pollination.3. Flowering periods uncoordinated: male flowers open two weeks earlierthan female flowers, resulting in low fruit formation of 15%.4. Some researchers believe there is a possible undiagnosed problem withthe floral structure, resulting in high rates of ovule abortion, or embryodeath. Grimshaw & Bayton (2009) reports 12.2% of cones with no seed(parthenocarpic).5. Nos. 3 and 4 are compounded by a poor seed germination rate of 15% inthe wild at Huaping. Grimshaw & Bayton (2009) reports a seed germinationrate of 21% (averaged across the various reserves?). [Tang Xiyang(1987) reported that initially only 4% could be germinated in cultivation].6. Severe in-breeding is affecting natural regeneration.7. Germination capacity of seeds is soon lost at normal temperatures due toa high oil content.8. The seeds are eaten by rodents such as mountain rats which consumedthe seeds of all but three of 102 cones under observation during ascientific study. Other predators of the silver fir seed are flying squirrelsand silver pheasants. The silver pheasant also devours the seedlings.9. Very poor natural regeneration is compounded by damping-off and thedifficulty of seedling roots penetrating the thick moss layer prevalent inareas of <strong>Cathaya</strong> populations. Removal of the moss results in soil erosion,either dislodging seedlings or suffocating them under mud flows duringrain periods.10. Slow growing seedlings perish under leaf litter due to lack of light.11. Seedlings initially need a certain amount of shade but once establishedafter a year or so have, as a heliophyte, a high light requirement anddislike dense shady environments under the forest canopy, where theyonly survive one to two years. Seedlings protected from browsing animals101YEARBOOK 2011

CATHAYA ARGYROPHYLLAbeneath understorey shrubs such as evergreen rhododendrons rarelysurvive five years. Juvenile plants not in optimal light suffer dieback.12. Seedlings suffer blight during the dry autumn season.13. The pine caterpillar Dendrolimus kikuchii is fond of silver fir foliage,consuming up to 30 leaves a day and can devour the leaves of a seedlingin a short period, causing it to perish. It is a major threat to <strong>Cathaya</strong>, amodern day defoliator replacing the dinosaurs who probably fed on thefoliage back in the Cretaceous when <strong>Cathaya</strong> occurred in at least Asiaand North America (For the fossil record see Liu & Basinger 2000, formolecular evidence see Lin et al., 2010 and Wang 2000).102To say as some do that <strong>Cathaya</strong> is adequately protected in inaccessible areas ismisinformed, as the Chinese consider “almost all extant <strong>Cathaya</strong> <strong>argyrophylla</strong>face serious threats and a high risk of extinction because of habitat deteriorationand loss” (Wang et al., 2010. Am. J. Bot. 97: 17). The Huaping population whichwas the largest in the 1980s has been severely reduced as previously mentionedand as this population extends over only 15km, the entire population couldbe wiped out in a wildfire if the experience in Australia is anything to goby. Here, out-of-control firestorms in the last decade or so of drought andsoaring temperatures as a result of global warming (no country is immune),have shocked people as they have raged at speeds in excess of 100kph overlong distances. This means that Huaping or other populations could bephotographs © Australian Bicentennial Arboretum (ABA)Above, rarely observed receptive flowers of <strong>Cathaya</strong>,awaiting a dusting of pollen during spring from malestrobili, on the older shoots below, left, or from anadjacent tree.INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY

TREESphotograph © Australian Bicentennial Arboretum (ABA)photograph © gxibReproduced with the kind permission of Xu Wei-binLeft, goodbye bracts, hello scales! Fourteen months after pollination the finely-pubescent scalescontaining the now fertilised ovules commence to cover the pointed bracts.Right, maturing cones containing the seeds of the next generation of Cathay silver firs which willbe released in October, four months after fertilization, or 18 months from pollination. The coneswill then remain on the branches for a number of years 4 .devastated in a matter of hours – fire has no respect for reserve boundaries.Also, not all <strong>Cathaya</strong> reserves are so inaccessible so as to prevent logging,which occurred at Huaping after the discovery of its virgin forests in 1954before it received legal protection in 1961. The small populations at BaizangShan, Tongzi county, Guizhou and at Baizhi Shan, Chongqing Municipality,which had ten trees with a maximum height of 5m and 52 trees with a maximumheight of 8m respectively recorded in the 1989 census (Mao 1989),indicates that at least these further two populations were accessible andlogged last century, possibly in the decades before, but more likely during theCultural Revolution which occurred between 1966 - 1976. Richard Primack(1988) gives an insight into the chaos that occurred during those years,particularly in respect to the extensive damage done to the forests of theeastern coastal province of Fujian and the persecution of officers of the ForestDepartment that had managed that province’s forests for sustained yield forhundreds, if not thousands of years. As Primack explains, once these officershad lost control of the forests by 1970, unsupervised cutting of trees, startingas a trickle, soon exploded into a six-year orgy of illegal logging that resultedin large tracts of the province being denuded of timber trees. Since he goes onto say that this wholesale destruction of forests occurred to a greater or lesserextent throughout China during this period, it is probable that the same fatebefell the forests at Baizang and Baizhi mountains, and that possibly thoselogging the virgin forests at Huaping in the second half of the 1950s returnedsix years later to take advantage of the free-for-all. Due to the valuablehigh-grade timber of the tall and straight Cathay silver fir which is suitablefor construction, shipbuilding, railway ties and furniture (Tang 1987), it is103YEARBOOK 2011

CATHAYA ARGYROPHYLLAAppendix Alternative Chinese names for people and places106PERSON’S NAME IN TEXT ALTERNATIVE NAME(S)CHENG Wan-chunCHENG Huan-yong, ZHENG Wan-junCHUN Woon-youngCHEN Huan-yung, CHEN Huan-yongKUANG Ko-zenKUANG Ko-jen, KUANG Ke-renL. K. FU (FU Li-kuo) FU Li-guoSUGATCHEY SUKACHEV (?)YANG Hsien-chinYANG Xian-jin, YANG Yen-chin, Y. C. YANGZHONG Ji-xinTSOONG Chi-hsinPLACE NAME IN TEXTALTERNATIVE NAME(S)CHUNGKINGCHONGQINGJINFU SHAN (mountain)JINFO SHANKIALING JIANG (river)JIALING JIANGKIANGSUJIANGSUKWANGSIGUANGXIHUAPINGFA PENGLUNGSHENGLONGSHENGNANKINGNANJINGPEKINGPEIPING, BEIJINGPEI-PEIBEIBEISZECHUANSICHUANAcknowledgements China/Australia/SingaporeI gratefully acknowledge Wang Yin-zheng for his kind permission to reproduce Y. C. Yang’sherbarium specimen. Also to Xu Wei-bin for permission to reproduce photos of the treeand cones of <strong>Cathaya</strong> and the black and white photo of Zhong Ji-xin (superimposed on1955 specimen). Zou Hong-fei is thanked for the black and white photo of Yang Hsien-chin(superimposed on 1938 specimen). Andy Ng in Sydney is thanked for his translating skills.Assisting in my research of this article were the following botanical colleagues in Singapore,Australia, and China to whom I would like to extend my thanks for their time and patience inanswering my numerous enquiries and requests. Also especially to my arboretum colleagueS. K. Png for his help with this article above and beyond the call of duty!Miguel Garcia, Librarian, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney ◊ Dr Russell Heng, Academic andauthor, Singapore ◊ Liao Zuo-qin (Zoe), Mianyang City, Sichuan ◊ Prof. Liu Yan, HerbariumDirector and Curator, Guangxi Institute of Botany, Yanshan, Guilin ◊ Prof. Ma Jin-shuang,Vice Director, Chenshan Plant Science Research Centre, Chinese Academy of Sciences,Shanghai ◊ Prof. Tang Ya, Department of the Environment, Sichuan University, Chengdu ◊ Prof.Wang Yin-zheng, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing ◊ Lorrae West,Librarian, Adelaide Botanical Gardens, South Australia ◊ Dr Xu Wei-bin, Herbarium,Guangxi Institute of Botany, Yanshan, Guilin ◊ Dr Yan Liang, Managing Editor, Journalof Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Beijing ◊ Dr Yang Zhi-rong, National Herbarium,Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing ◊ Prof. Zhang Xian-chun, Director,National Herbarium, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing ◊ Prof. ZouHong-fei, Director, <strong>International</strong> Cooperation Office, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin.INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY