Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia - Universidade Federal do Acre

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia - Universidade Federal do Acre

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia - Universidade Federal do Acre

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

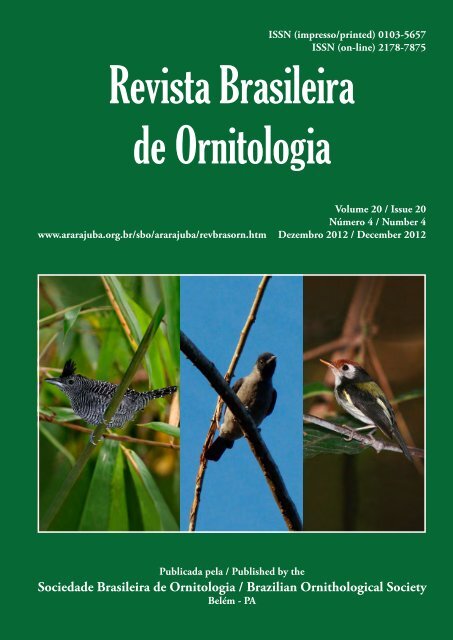

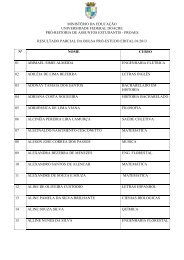

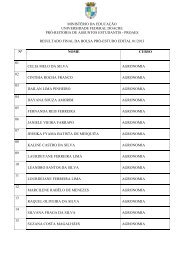

<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>EDITOR / EDITOR IN CHIEFAlexandre Aleixo, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi / Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação, Belém, PA.E-mail: aleixo@museu-goeldi.brSECRETARIA DE APOIO À EDITORAÇÃO / MANAGING OFFICEFabíola Poletto – Instituto Nacional <strong>de</strong> Pesquisas EspaciaisBianca Darski Silva – Museu Paraense Emílio GoeldiEDITORES DE ÁREA / ASSOCIATE EDITORSArtigos publica<strong>do</strong>s na <strong>Revista</strong> Carlos <strong>Brasileira</strong> A. Bianchi, <strong>de</strong> Universida<strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral são <strong>de</strong> in<strong>de</strong>xa<strong>do</strong>s Goiás, Goiânia, por: GOBiological Abstract, Scopus (Biobase, Ivan Sazima, Geobase Universida<strong>de</strong> e EMBiology) Estadual <strong>de</strong> Campinas, e Zoological Campinas, Record. SPComportamento / Behavior:Cristiano Schetini <strong>de</strong> Azeve<strong>do</strong>, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>de</strong> Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, MGManuscripts Conservação / Conservation: published by <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> Alexan<strong>de</strong>r <strong>Ornitologia</strong> C. Lees, Museu are covered Paraense Emílio by the Goeldi, following Belém, PAin<strong>de</strong>xing databases:Ecologia Biological / Ecology: Abstracts, Scopus (Biobase, Geobase, and EMBiology), and Zoological Records.Sistemática, Taxonomia e Distribuição /Systematics, Taxonomy, and Distribution:Caio Graco Macha<strong>do</strong>, Universida<strong>de</strong> Estadual <strong>de</strong> Feira <strong>de</strong> Santana, Feira <strong>de</strong> Santana, BAJames J. Roper, Universida<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> Vila Velha, Vila Velha, ESLeandro Bugoni, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>do</strong> Rio Gran<strong>de</strong>, Rio Gran<strong>de</strong>, RSLuís Fábio Silveira, Universida<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> São Paulo, São Paulo, SPLuiz Antônio Pedreira Gonzaga, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>do</strong> Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, RJBibliotecas <strong>de</strong> referência para o <strong>de</strong>pósito da versão impressa: Biblioteca <strong>do</strong> Museu <strong>de</strong> ZoologiaMarcos Pérsio Dantas Santos, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>do</strong> Pará, Belém, PAda USP, SP; Biblioteca <strong>do</strong> Museu Nacional, RJ; Biblioteca <strong>do</strong> Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi,PA; National Museum of Natural History Edwin Library, O. Willis, Smithsonian Universida<strong>de</strong> Estadual Institution, Paulista, Rio USA; Claro, Louisiana SP StateEnrique Bucher, Universidad Nacional <strong>de</strong> Cór<strong>do</strong>ba, Argentina.University, Museum of Natural Science, USA; Natural History Museum at Tring, Bird Group, UK.CONSELHO EDITORIAL / EDITORIAL COUNCILRichard O. Bierregaard Jr., University of North Carolina, Esta<strong>do</strong>s Uni<strong>do</strong>sJosé Maria Car<strong>do</strong>so da Silva, Conservation International, Esta<strong>do</strong>s Uni<strong>do</strong>sReference libraries for the <strong>de</strong>posit of the Miguel printed Ângelo Marini, version: Universida<strong>de</strong> Biblioteca <strong>de</strong> Brasília, <strong>do</strong> Museu Brasília, DF <strong>de</strong> Zoologia daUSP, SP; Biblioteca <strong>do</strong> Museu Nacional, RJ; Biblioteca <strong>do</strong> Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, PA;National Museum of Natural History Library, Smithsonian Institution, USA; Louisiana StateUniversity, Museum of Natural Science, USA; Natural History Museum at Tring, Bird Group, UK.Luiz Antônio Pedreira Gonzaga, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>do</strong> Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, RJ** O trabalho <strong>do</strong> Editor, Secretaria <strong>de</strong> Apoio à Editoração, Editores <strong>de</strong> Área e Conselho Editorial da <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong> é estritamente voluntárioe não implica no uso <strong>de</strong> quaisquer recursos e infraestrutura que não sejam pessoais**** The work of the Editor in Chief, Managing Office, Associate Editors, and the Editorial Council of <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong> is strictly voluntary, and<strong>do</strong>es not involve the use of any resources and infrastructure other than the personal ones**SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA DE ORNITOLOGIA(Fundada em 1987 / Established in 1987)www.ararajuba.org.brDIRETORIA /Presi<strong>de</strong>nte / presi<strong>de</strong>nt: Cristina Yumi Miyaki, Universida<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> São Paulo, São Paulo, SPELECTED BOARD1° Secretária / 1 st Secretary: FICHA Carla Suertegaray CATALOGRÁFICAFontana, Pontifícia Universida<strong>de</strong> Católica <strong>do</strong> Rio Gran<strong>de</strong> <strong>do</strong> Sul, Porto-Alegre, RS(2011-2013) sbo.secretaria@gmail.com2° Secretária / 2 nd Secretary: Maria Alice <strong>do</strong>s Santos Alves, Universida<strong>de</strong> <strong>do</strong> Esta<strong>do</strong> <strong>do</strong> Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro, RJ1° Tesoureira <strong>Revista</strong> / 1 st Treasurer: <strong>Brasileira</strong> Celine <strong>de</strong> Melo, <strong>Ornitologia</strong> Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral / Socieda<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> Uberlândia, <strong>Brasileira</strong> Uberlândia, MG <strong>de</strong> - tesouraria@gmail.com2° Tesoureira <strong>Ornitologia</strong>. / 2 nd Treasurer: Luciana Vol. Vieira 20, <strong>de</strong> n.1 Paiva, (2012) Faculda<strong>de</strong> - Anhanguera <strong>de</strong> Brasília, Brasília, DFBelém, A Socieda<strong>de</strong>, 2005 -CONSELHO DELIBERATIVO / 2008-2012 v. : il. ; 30 Caio cm. Graco Macha<strong>do</strong>, Universida<strong>de</strong> Estadual <strong>de</strong> Feira <strong>de</strong> Santana, Feira <strong>de</strong> Santana, BAELECTED COUNCILORS 2011-2015 Márcio Amorim Efe, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>de</strong> Alagoas, Maceió, ALJames J. Roper, Universida<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> Vila Velha, Vila Velha, ESContinuação <strong>de</strong>:. Claiton Ararajuba: Martins Ferreira, Vol.1 Universida<strong>de</strong> (1990) Fe<strong>de</strong>ral - 13(1) <strong>do</strong> Rio (2005). Gran<strong>de</strong> <strong>do</strong> Sul, Porto Alegre, RSMárcia Cristina Pascotto, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>de</strong> Mato Grosso, Barra <strong>do</strong> Garças, MTCONSELHO FISCAL / 2011-2013 Fabiane Sebaio <strong>de</strong> Almeida, Associação Cerra<strong>do</strong> Vivo para Conservação da Biodiversida<strong>de</strong>, Patrocínio, MGFINNANCIAL COUNCILRudi Ricar<strong>do</strong> Laps, Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>de</strong> Mato Grosso <strong>do</strong> Sul, Campo Gran<strong>de</strong>, MSISSN: 0103-5657 Paulo <strong>de</strong> Tarso (impresso) Zuquim Antas, PTZA Consultoria e Meio Ambiente, Brasília, DFISSN: 2178-7875 (on-line)A <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong> (ISSN 0103-5657 e ISSN 2178) é um periódico <strong>de</strong> acesso livre edita<strong>do</strong> sob a responsabilida<strong>de</strong> da Diretoria e <strong>do</strong> ConselhoDeliberativo da Socieda<strong>de</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, com periodicida<strong>de</strong> trimestral, e tem por finalida<strong>de</strong> a publicação <strong>de</strong> artigos, notas curtas, resenhas, comentários, revisõesbibliográficas, notícias e editoriais versan<strong>do</strong> sobre1.o estu<strong>do</strong><strong>Ornitologia</strong>.das aves em geral,I.comSocieda<strong>de</strong>ênfase nas aves<strong>Brasileira</strong>neotropicais. To<strong>do</strong>s<strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>.os volumes <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong> po<strong>de</strong>mser acessa<strong>do</strong>s gratuitamente através <strong>do</strong> site http://www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/revbrasorn.htmThe <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong> (ISSN 01035657 e ISSN 2178-7875) is an open access jornal edited by the Elected Board and Councilors of the BrazilianOrnithological Society and published four times a year. It aims to publish papers, short communications, reviews, news, and editorials on ornithology in general, with anemphasis on Neotropical birds. All volumes of <strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong> can be <strong>do</strong>wloa<strong>de</strong>d for free at http://www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/revbrasorn.htmProjeto Gráfico e Editoração Eletrônica / Graphics and electronic publishing: Regina <strong>de</strong> Siqueira Bueno (e-mail: mrsbueno@gmail.com).Capa: Três espécies <strong>de</strong> aves típicas das florestas <strong>de</strong> bambu <strong>do</strong> esta<strong>do</strong> <strong>do</strong> <strong>Acre</strong>, cuja avifauna é analisada neste volume por Guilherme (da esquerda para a direita): choca<strong>do</strong>-bambu(Cymbilaimus sanctaemariae; Foto: Andrew Whittaker), anambé-<strong>de</strong>-cara-preta (Conioptilon mcilhennyi; Foto: Edson Guilherme) e ferreirinho-<strong>de</strong>-cara-branca(Poecilotriccus albifacies; Foto: Andrew Whittaker).Front cover: Three bird species typical of the bamboo <strong>do</strong>minated forests in the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>, whose avifauna is analyzed in this volume by Guilherme (fromleft to right): Bamboo Antshrike (Cymbilaimus sanctaemariae; Photo: Andrew Whittaker), Black-faced Cotinga (Conioptilon mcilhennyi; Photo: Edson Guilherme), andWhite-cheeked Tody-Tyrant (Poecilotriccus albifacies; Photo: Andrew Whittaker).

<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>Volume 20 – Número 4 – Dezembro 2012 / Issue 20 – Number 4 – December 2012SUMÁRIO / CONTENTSartigos / PAPERSBirds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme ............................................................................................................................................................First record of Augastes scutatus for Bahia refines the location of a purported barrier promoting speciation in theEspinhaço Range, BrazilMarcelo Ferreira <strong>de</strong> Vasconcelos, An<strong>de</strong>rson Vieira Chaves and Fabrício Rodrigues <strong>do</strong>s Santos.................................................Records of the Crowned Eagle (Urubitinga coronata) in Moxos plains of Bolivia and observations about breedingbehaviorIgor Berkunsky, Gonzalo Daniele, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico P. Kacoliris, Sarah I. K. Faegre, Facun<strong>do</strong> A. Gan<strong>do</strong>y, Lyliam González andJosé A. Díaz Luque..........................................................................................................................................................393443447NOTAS / SHORT-COMMUNICATIONSPredation of Long–tailed Silky Flycatcher (Ptilogonys caudatus) by Ornate Hawk–Eagle (Spizaetus ornatus) in a cloudforest of Costa RicaVíctor Acosta-Chaves, Fe<strong>de</strong>rico Grana<strong>do</strong>s-Rodríguez and David Araya-Huertas...................................................................First record of the Chaco Earthcreeper Tarphonomus certhioi<strong>de</strong>s (Furnariidae), in Brazil.Márcio Repenning, Eduar<strong>do</strong> Chiarani, Mauricio da Silveira Pereira and Carla Suertegaray Fontana...................................A first <strong>do</strong>cumented Brazilian record of Least Seedsnipe Thinocorus rumicivorus Eschscholtz, 1829 (Thinocoridae)Felipe Castro, João Castro, Aluisio Ramos Ferreira, Marco Aurélio Crozariol and Alexan<strong>de</strong>r Charles Lees...............................451453455Instructions to Authors

<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 393-442Dezembro <strong>de</strong> 2012 / December 2012artigo/ARTICLEBirds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity,zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme 11Universida<strong>de</strong> Fe<strong>de</strong>ral <strong>do</strong> <strong>Acre</strong>, Museu Universitário, Laboratório <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>. Campus Universitário - BR 364, Km 04, Distrito industrial, RioBranco - <strong>Acre</strong>, Brazil. CEP: 69915-900. E-mail: guilherme@ufac.br.Received 12 March 2012. Accepted 27 July 2012.ABSTRACT: The Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> bor<strong>de</strong>rs Peru and Bolivia to the west and south, and the Brazilian states of Amazonas andRondônia to the north and east, respectively. The state is located within the lowlands of the western Amazon basin, adjacent to thefoothills of the An<strong>de</strong>s, within a “megadiverse” region of the Brazilian Amazon basin. Despite its diversity, the region is still onlypoorly known in scientific terms, and is consi<strong>de</strong>red to be a priority for future biological surveys. Given this situation, the presentstudy aims to contribute to the scientific knowledge of the avian fauna of southwestern Amazonia, by evaluating the followingquestions – (a) how many and which bird species occur in the state of <strong>Acre</strong>?; (b) how are these species distributed within the state?;and (c) what are the priority areas for new ornithological surveys within the state of <strong>Acre</strong>? My metho<strong>do</strong>logical procedures inclu<strong>de</strong>d(a) a wi<strong>de</strong> literature search; (b) two years of field surveys, including observation records and the collection of voucher specimens;(c) map the distribution of avian taxa within the two main interfluvial regions (east and west of the Purus River) of the state; and(d) the i<strong>de</strong>ntification of contact and possible hybridization zones, based on the distribution of parapatric sister taxa. The literaturesearch and fieldwork resulted in the compilation of 9550 avian records, encompassing 4763 specimens, of which 2457 (51.5%) werecollected during the past five years. A total of 667 species were confirmed for the state of <strong>Acre</strong>, representing 75 families and 23 or<strong>de</strong>rs.A total of 64 migratory species were also recor<strong>de</strong>d, of which 46.8% (n=30) are Nearctic migrants, 15 (23.4%) were consi<strong>de</strong>red tobe intratropical migrants, and 19 (29.6%) were classified as austral migrants. Overall, 41 of the recor<strong>de</strong>d species and subespecieswere en<strong>de</strong>mic to the Inambari center of en<strong>de</strong>mism. Of all forest avian taxa present year round in the state, 79% are distributed inboth main interfuvial regions, 16% were recor<strong>de</strong>d only in the central-western sub-region (west of the Purus), and 5% only in theeastern sub-region (east of the Purus). At least five pairs of purported sister taxa presented allopatric distributions, whereas 15 hadparapatric distribution within the state. Two zones of secondary contact (east and west) were i<strong>de</strong>ntified, which coinci<strong>de</strong>d with twopossible hybridization zones. The main conclusions of this study are: (a) the total number of species recor<strong>de</strong>d in the state is high butwill probably increase as new surveys are conducted; (b) neither of the state’s major rivers – the Purus and the Juruá – act as physicalbarriers to the dispersal of most of the resi<strong>de</strong>nt species found in the state; (c) the zones of secondary contact found <strong>do</strong> not coinci<strong>de</strong>with the basins of these two major rivers, which supports the i<strong>de</strong>a that factors other than physical barriers to dispersal <strong>de</strong>terminethe present distribution of some of the resi<strong>de</strong>nt bird taxa of <strong>Acre</strong>; and (d) birds restricted to the white-sand forests (campinas andcampinaranas) found only in the western portion of the state, as well as those found only in the <strong>de</strong>nse forests of eastern <strong>Acre</strong>,constitute together the most threatened elements of the state’s avifauna since no conservation units protect these specific habitats.KEY-WORDS: Amazonia; areas of en<strong>de</strong>mism; contact zones; hybridization; Purus; white sand forests.INTRODUCTIONThe Amazon basin encompasses the largest andmost diverse tract of continuous tropical rainforestfound anywhere in the World. Covering more than sixmillion square kilometers in nine countries of northernSouth America, the region is home to more than 40,000plant species, 427 mammals, 1294 birds, 378 reptiles,427 amphibians, and more than 3,000 species of fish,representing around 10% of the planet’s biodiversity(Mittermeier et al. 2003). Despite this biologicalrichness, few of the plans proposed for the <strong>de</strong>velopmentof the region have contemplated the effective protectionof these natural resources. In most cases, this is justifiedby the lack of a<strong>de</strong>quate information on this diversity,which might enable its inclusion in the <strong>de</strong>cision-makingprocesses un<strong>de</strong>rpinning strategic planning. However,relatively little has been <strong>do</strong>ne to compile the existing dataand catalog the species that occur in the region, or theirgeographic ranges.Brazil has one of the richest avian faunas inSouth America, with a current total of 1832 species(CBRO 2011). Despite this diversity and the fact thatornithological research began in Brazil in the 16thcentury, the first systematic catalog of Brazilian birds wasonly produced in the mid-20th century (Pinto, 1938;1944; 1978). The seminal work on the country’s birdsis that of Sick (1985; 1997), which provi<strong>de</strong>s <strong>de</strong>tailed

Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme395meandrous—their courses change constantly, resulting ina mosaic of oxbow lakes and islands throughout the basin(Toivonem et al. 2007). This process favors the migrationor passive dispersal of animals between margins (Ayres& Clutton-Brock 1992; Silva et al. 2005a; Haffer 2001).These whitewater rivers inclu<strong>de</strong> the Purus and Juruá in thesouthwestern Amazon basin, which are two of the majorright-bank tributaries of the Solimões (Amazon River).Whatever the color of their water, however, all the majorrivers, such as the Amazon, Tapajós and Negro, tend to beless effective as barriers in their headwater reaches, wheretheir margins are much closer together (Haffer 1992b;2001; Hayes & Sewlal 2004).A common distribution pattern in the Amazonbasin is the occurrence of two or more closely relatedtaxa within contact zones. These contact zones are oftencharacterized by the parapatric distribution of sister taxawithin a relatively narrow and well-<strong>de</strong>fined area (Haffer1987). Parapatric taxa occur in adjacent areas (Haffer1992a), which are often <strong>de</strong>limited by physical or ecologicalbarriers, although in some cases, there is contact, and evenoverlap between their geographic ranges (Haffer 1992a;1997; Aleixo 2007). In some cases, these contact zonesare characterized by intense interspecific competition(Haffer 1986; 1987; 1992a; Price, 2008). One of thedirect consequences of this contact is the possibility ofgene flow between neighboring populations, <strong>de</strong>pendingon the genetic similarity of the taxa involved, which maylead to hybridization (Haffer 1986; 1997; Price, 2008)and the formation of distinct hybrid zones (Haffer 1987).These zones are usually characterized by the coexistenceof pure and hybrid individuals within the same areas(Aleixo 2007).Contact zones may be either primary or secondary.Primary contact zones arise as a consequence of thedifferentiation of local populations in response to selectionpressures associated with environmental gradients (Endler1982), whereas secondary zones are the result of the reencounterof previously isolated populations, whichhave differentiated un<strong>de</strong>r distinct ecological conditions(Haffer 1997). Haffer (1987, 1997) believed that allcontact zones between Amazonian birds are secondary,resulting from the geographic expansion of sister taxa,which were previously isolated in forest refuges, as aconsequence of global climate changes. In this case, thepresence of contact zones may indicate the location ofancient ecological barriers, which have disappeared overtime (Haffer 1987).Ornithological research in the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>Ornithological research in <strong>Acre</strong> only began inthe 1950s, when two pioneering expeditions wereun<strong>de</strong>rtaken in what was, at the time, still only a Brazilianterritory rather than a state. The first of these took placein the eastern portion of the territory (Vanzolini, 1952;Pinto & Camargo, 1954), with the subsequent excursionexploring the western portion (Novaes, 1957; 1958).Eastern <strong>Acre</strong> was visited firstly by the privatecollector José Hidasi, in 1968, and then in 1976 byGeral<strong>do</strong> Pereira da Silva, an employee of the EvandroChagas Institute in Belém. Records of some of thespecimens collected during these expeditions can befound in the ornithological literature (Novaes 1978;Pierpont & Fitzpatrick 1983; Teixeira et al. 1994; Hidasi& Bankovics 1997; Sick 1997).During the 1990s, a number of professionalornithologists visited western <strong>Acre</strong>, in particular the Serra<strong>do</strong> Divisor National Park and the Alto Juruá ExtractivistReserve. The occurrence of more than 500 local species ofbirds was recor<strong>de</strong>d during these expeditions (Whittaker& Oren 1999; Whittaker et al. 2002).In 2005, I began the research for my <strong>do</strong>ctoraldissertation, which was entitled “Bird fauna of theBrazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, andconservation”. This project inclu<strong>de</strong>d more than 20expeditions to poorly-known or unexplored areas withinthe state. The results of this research were presented in mydissertation (Guilherme 2009) and have been publishedin a number of papers (Guilherme 2007; Guilherme &Santos 2009; Aleixo & Guilherme 2010; Guilherme &Borges 2011; Guilherme & Dantas 2011a).During this same period, Dante Buzzetti carried outa <strong>de</strong>tailed ornithological survey of the Chandless StatePark (Buzzetti 2008), while Luiz Mestre and GregoryThom studied the bird communities in areas affected byfire within the Chico Men<strong>de</strong>s Extractivist Reserve (Mestreet al. 2010a). The compilation of the data from all thesestudies and the <strong>de</strong>scription of the distribution patterns ofthe bird species in the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> constitutethe principal theme of this paper.MATERIAL AND METHODSStudy AreaThe Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> in located in thesouthwestern Amazon basin, bor<strong>de</strong>ring Bolivia and Peruto the south and west, and the Brazilian states of Amazonasand Rondônia to the north and east, respectively (Figure1). The state covers a total area of 164,221.36 km², whichcorresponds to 4.26% of the area of Brazil’s northernregion, and 1.92% of the country as a whole (Governo<strong>do</strong> <strong>Acre</strong> 2012).Most of the state is located within two adjacenthydrographic basins, that of the Purus River, in theeastern and central portions of the state, and the Juruá,in the west (Figure 2). All the watercourses of these twobasins belong to the hydrographic basin of the Amazon<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

396Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson GuilhermeFIGURE 1. Location of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> with respect to other neighboring national states and countries.FIGURE 2. Location of the two main hydrographic basins within the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>, roughly corresponding to the western and eastern subregionsof the state as a<strong>do</strong>pted here.<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme397River. The state’s drainage system is well distributed, andis composed of mean<strong>de</strong>ring rivers with short straightchannels that flow over sedimentary rocks mainly in asouthwest to northeast direction.The climate of <strong>Acre</strong> is hot and humid, with therelative humidity of the air ranging from 80% to 90%.As in other parts of the Amazon basin, there are twomain climatic seasons – a dry season, from May toOctober, when precipitation <strong>de</strong>creases substantially, anda rainy season, from November to April, when rainfallis almost constant (Duarte & Marcarenhas 2007).Abrupt cold snaps are common during the dry season.This phenomenon is known locally as “friagem”, and isthe result of the movement of polar fronts, which areforced northwards by the Atlantic Polar Air Mass, whichadvances over the Chaco plain to western Amazonia (<strong>Acre</strong>2000). Annual precipitation ranges from 1600 mm to2750 mm, with the highest values being recor<strong>de</strong>d in thewest of the state, which is closer to the equator, and hassuffered less habitat <strong>de</strong>struction, while the lowest rainfalllevels occur in the eastern portion of the state, which isless preserved (Cunha & Duarte, 2005).Three subtypes of climate can be found in the state,following Köppen’s classification (Duarte 2007). In thisscheme, the climate of the Juruá basin can be assignedto subtype Af3, in which the precipitation in the driestmonth is above 60 mm, and the annual total is between2000 and 2500 mm (Cunha & Duarte, 2005; Duarte,2007, 2008). The Purus basin climate is classified as Am3,in which annual precipitation is the same as Af3, but thatof the driest month is lower, between 30 mm and 60 mm.The <strong>Acre</strong> River basin climate (subtype Am4) is even drier,with annual precipitation of 1500-2000 mm and meanrainfall in the driest month (June) of around 30 mm.The mean annual temperature of the state as a whole isapproximately 24.5°C, with a maximum of around 32°C(<strong>Acre</strong> 2000).The Ecological-Economic Zoning (EEZ) of thestate of <strong>Acre</strong> (<strong>Acre</strong> 2000) <strong>de</strong>fined three phyto-ecologicalregions – the <strong>de</strong>nse rainforest, open rainforest, and thecampinas-campinaranas (white-sand forest) <strong>do</strong>mains. Ihave a<strong>do</strong>pted this classification to i<strong>de</strong>ntify the principalhabitats occupied by the different bird species in thestate (Appendix 1). The principal characteristics of these<strong>do</strong>mains are as follows:Dense Rainforest (hereafter DRF): This <strong>do</strong>main ischaracterized by large trees (20-50 m in height), lianas,and epiphytes. The distribution of this habitat within thestate of <strong>Acre</strong> is related to that of tertiary and quaternarysediments in areas with annual precipitation above 2300mm, and average temperatures of 22° to 23°C (IBGE2005). These geomorphological and climatic conditionsprevail primarily in the west of the state, where theclimate is more humid (dry seasons are shorter) thanthe east. The diagnostic feature of this type of forest is auniform canopy with emergent trees and sparse or absentun<strong>de</strong>rgrowth (<strong>Acre</strong> 2000). Depending on the edaphicconditions and topography, the region’s DRFs can besubdivi<strong>de</strong>d into three distinct formations – alluvial,lowland, and submontane forests (IBGE, 2005).Open Rainforest (hereafter ORF): Like the <strong>de</strong>nserainforest, this type of forest is composed of mediumto large trees, but with a pre<strong>do</strong>minance of shrubbytrees and woody lianas (IBGE, 2005). This type ofhabitat is associated with areas of sedimentary rocks ofPlio-Pleistocene origin in lowland Amazonia, whichare characterized by undulating hills – the SolimõesFormation – or hilly interfluvia (<strong>Acre</strong> 2000). The ORFhabitats are found throughout most of <strong>Acre</strong>, on a varietyof geomorphological units, but can be subdivi<strong>de</strong>d intotwo formations – lowland and alluvial – based on edaphicand topographic criteria (IBGE, 2005). These habitatscan also be differentiated into a number of differentforest types, based on the relative <strong>do</strong>minance of palms,bamboos and/or lianas (IBGE 2005; <strong>Acre</strong> 2000).Campinas and Campinaranas: These habitats arefound throughout the Amazon basin, where they grow onwhite sandy soils (An<strong>de</strong>rson 1981; IBGE 2005; Silveira2003), which are extremely nutrient-poor and have ahighly permeable subsoil (Jirka et al. 2007). Given thesesoil characteristics, campinaranas have a relatively thicklayer of superficial roots when compared with othertypes of Amazonian vegetation (Jirka et al. 2007; Silveira2003). The campinas are characterized by irregular, openvegetation, with un<strong>de</strong>rgrowth of reduced stature. Thesehabitats are ma<strong>de</strong> up of relatively <strong>de</strong>nse stands of small,thin trees, with few emergent trees (Silveira, 2003). In <strong>Acre</strong>,campinaranas are only found in the Juruá basin, mainlyin the municipalities of Cruzeiro <strong>do</strong> Sul and MâncioLima. The habitats are normally found in areas drained byblackwater rivers, such as the Bagé and the Machadinho(<strong>Acre</strong> 2000). Silveira (2003) <strong>de</strong>scribed four distinct typesof white-sand vegetation in southwestern Amazonia – openshrubby campina, campina <strong>do</strong>minated by buriti (Mauritiaflexuosa) palms, campina grasslands, and campinaranasensu lato. In addition to the campinaranas located alongthe bor<strong>de</strong>r with the Brazilian state of Amazonas, a smallarea of this vegetation was sampled on the left bank ofthe Cruzeiro <strong>do</strong> Vale stream in the municipality of PortoWalter (Guilherme & Borges 2011).Literature searchI <strong>de</strong>rived a preliminary list of birds that occur in<strong>Acre</strong> from a systematic review of the available literature.The first step was to i<strong>de</strong>ntify and compile all the availablereferences to construct a database containing all therecords of birds available for the state. For each record,I searched for the following information: 1) the preciselocation of the observation and/or specimen collection;<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

398Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme2) species and, when available, subspecies i<strong>de</strong>ntification;3) the observer(s) and/or collector(s) associated with therecord; 4) the date of the record; and 5) when applicable,the institution in which the specimen(s) were <strong>de</strong>posited.I used these data to establish a spreadsheet in MicrosoftExcel® in which each line represented a record and eachcolumn contained the different types of informationlisted above. The next step was to update the scientificnomenclature of many records, given that the names ofsome general, species and the status of some subspecieshave changed during recent taxonomic reviews.The references I used to compile the preliminaryspecies list for the period between 1950 and 2005were Pinto & Camargo (1954), Novaes (1957; 1958),Whittaker & Oren (1999), Guilherme (2001),Whittaker et al. (2002), and Rasmussen et al. (2005). Thesubsequent period (since 2005) is covered by my <strong>do</strong>ctoralthesis (Guilherme 2009) and all subsequent publications(Guilherme & Santos 2009; Aleixo & Guilherme 2010;Guilherme & Dantas 2011a, Guilherme & Borges 2011,Mestre et al. 2010a).Specimens <strong>de</strong>posited in natural history museumsBased on the references reporting on theornithological expeditions conducted in <strong>Acre</strong>, I couldtrace the whereabouts of practically all bird specimenscollected in the state. Collections holding bird specimenscollected in <strong>Acre</strong> are the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi(MPEG), Museu <strong>de</strong> Zoologia da Universida<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong> SãoPaulo (MZUSP), Museu Nacional <strong>do</strong> Rio <strong>de</strong> Janeiro(MNRJ), Museu <strong>de</strong> Zoologia da Universida<strong>de</strong> Estadual<strong>de</strong> Campinas (ZUEC/UNICAMP), Louisiana StateUniversity Museum of Natural Sciences (LSUMZ), FloridaMuseum of Natural History (FMNH), and the AmericanMuseum of Natural History (AMNH). An additional 34specimens are <strong>de</strong>posited in the private collection of Prof.José Hidasi (CPJH), in Goiânia, Goiás (Brazil).The vast majority (ca. 85%) of the bird specimenscollected in <strong>Acre</strong> have been <strong>de</strong>posited in the Dr. Fernan<strong>do</strong>C. Novaes Collection of the Goeldi Museum in Belém,Brazil, and all of these specimens were examinedduring the present study. I obtained information on thespecimens from all other museums directly from thecurators responsible for each collection via electronic mail.Whenever a <strong>do</strong>ubt arose with regard to the i<strong>de</strong>ntificationor locality of a specimen, I contacted the curator onceagain. In these cases, the queries were resolved eithertextually or by photographs.LocalitiesI established a database for the cataloguing of allthe localities in <strong>Acre</strong> for which at least one avian recordis available, that is, at least one record in the literatureor a specimen <strong>de</strong>posited in a museum. For recordsobtained prior to 1990, I traced localities and theirrespective coordinates in the Ornithological Gazetteerof Brazil (Paynter & Taylor 1991). For records obtainedafter 1991, locality information and coordinates wereretrieved from the techni cal reports, scientific papers,and specimen labels. For the expeditions conductedby myself between 2005 and 2009 (Guilherme 2009),geographic coordinates were obtained directly in the fieldwith a Garmin 72® GPS receiver.Taxonomy and nomenclatureHere, I a<strong>do</strong>pt the taxonomy and nomenclature ofthe Brazilian Checklist Committee (CBRO 2011). At thepresent time, this Committee recognizes a total of 1832bird species in Brazil, representing 95 families distributedin 26 or<strong>de</strong>rs. The presence of a number of polytypicspecies represented by distinct, parapatrically-distributedsubspecies was recor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong>. For the zoogeographicanalyses, I treated all subspecies that could be diagnosedand were consi<strong>de</strong>red to be allopatric / parapatric as distincttaxa, following the recommendation of Aleixo (2007).Subspecific i<strong>de</strong>ntification of species represented by morethan one visibly diagnosable taxon in <strong>Acre</strong> was initiallybased on analyses of series of specimens <strong>de</strong>posited atMPEG. Confirmation of <strong>de</strong>scriptions of these subspeciesand their geographic distributions were obtained in Pinto(1978), Isler & Isler (1999), Restall et al. (2006), and <strong>de</strong>lHoyo et al. (1992, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2002,2003, 2004, 2005, 2006).Species statusI classified the bird species recor<strong>de</strong>d during thepresent study as resi<strong>de</strong>nt or migrant. I consi<strong>de</strong>red speciesto be resi<strong>de</strong>nt if they breed within the limits of the stateof <strong>Acre</strong>. I i<strong>de</strong>ntified three groups of resi<strong>de</strong>nts: nativespecies (native to the Amazon basin), inva<strong>de</strong>rs (native toother South American biomes, and which only entered<strong>Acre</strong> following anthropogenic modifications of theenvironment), and introduced species (native to othercontinents).I inferred a resi<strong>de</strong>nt status based on gonad size ofspecies represented by museum specimens as well dataavailable in the literature. Some sources, such as Hilty &Brown (1986), Ridgely & Tu<strong>do</strong>r (1994; 2009), Stotz et al.(1996), Sick (1997), Schulenberg et al. (2007), and theHandbook of the Birds of the World collection provi<strong>de</strong>important information on the reproductive behavior ofAmazonian species. Birds classified as migratory are thoseknown to breed outsi<strong>de</strong> the Amazon basin. Based on the<strong>de</strong>finition of Hayes (1995), three groups of migratorybirds are found in <strong>Acre</strong> – Nearctic, intratropical, andaustral migrants. The Nearctic migrants breed in North<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme399America and migrate to South America during the borealwinter. Intratropical migrants breed in the tropics, in thepresent case, South America, but migrate regularly toother areas within the same continent (Jahn et al., 2006;Hayes, 1995). This category inclu<strong>de</strong>s only species thatbreed in other biomes – e.g., Cerra<strong>do</strong>, Pantanal, Chaco– and then migrate to the Amazon basin. The australmigrants are the species that breed in southern SouthAmerica and then migrate northwards during the winter.Zoogeography and i<strong>de</strong>ntification of contact/hybridization zonesI tested whether the Purus River representsan important barrier and is associated with a majorbiogeographic break in the distribution of resi<strong>de</strong>nt forestbirds in <strong>Acre</strong> by arbitrarily dividing the state into twoportions (west and east of this river), and calculating thesimilarity in species composition between these areas.Because of their overall high dispersal capabilities, neithermigratory species, nor those associated with aquatic habitats(Anatidae, Podicipedidae, Phalacrocoracidae, Anhingidae,Ar<strong>de</strong>idae, Ciconidae, Aramidae, Heliornithidae, Jacanidae,Sternidae, Rynchopidae, and Alcedinidae), were inclu<strong>de</strong>din this analysis. I used Microsoft Excel® for the productionand analysis of the matrix.I based the i<strong>de</strong>ntification of possible contact zoneson the selection of all taxa assumed to 1) be sister orclosely related species within a genus; or 2) representsubspecies grouped un<strong>de</strong>r the same polytypic species,that are parapatrically distributed within the state of<strong>Acre</strong>, i.e., represented by adjacent populations within aspecific area (Haffer 1997; Aleixo 2007). I i<strong>de</strong>ntified thecontact zones using the approach of Haffer (1987, 1997),which first establishes a “core” region of the distributionof each taxon, and then the overall limits of its range. Thehorizontal or vertical position of the contact zone was<strong>de</strong>fined according to the expansion of the distributionof each taxon, that is, with a north/south or east/westexpansion of the geographic range (and vice versa). Thegeneral distribution of each taxon estimated based onPinto (1978), Ridgely & Tu<strong>do</strong>r (1994, 2009), InfoNatura(2007), Schulenberg et al. (2007), and the Handbook ofthe Birds of the World series.If specimens were available from a purportedcontact zone, they were analyzed to <strong>de</strong>termine whetheror not hybrids could be found within the zone. Ahybridization zone can be <strong>de</strong>tected through the presenceof hybrid specimens in close proximity to a contact zone.The i<strong>de</strong>ntification of potential hybrid specimens wasbased on the visual inspection of plumage characteristicsand other external morphological characters. However,it is important to note that any inferred hybrid statusis tentative and can only be confirmed throughcomplementary genetic studies.Checklist compilationThe inventory of the bird species that occur in theBrazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> was compiled based on the criteriaproposed by Carlos et al. (2010), with the records beinggrouped in two distinct lists:a) The primary list: all the species with confirme<strong>do</strong>ccurrence via vouchered <strong>do</strong>cumentation(specimens, photos or audio recording) in thestate of <strong>Acre</strong>;b) The secondary list: species that are reported tooccur in the state, but have not been confirmedthrough observations or specimens, as well asspecies known to occur in neighboring areas,which are assumed to occur (“probableoccurrence”) in <strong>Acre</strong>, based on their distributionpattern and ecological characteristics.RESULTSSpecies richness and compositionA total of 9550 bird records were compiled for thestate of <strong>Acre</strong>. Of these, 4763 are specimens <strong>de</strong>posited inmuseums, more than half of which (51.5%, n = 2457)were collected during the past five years (Guilherme2009). Overall, it was possible to confirm the occurrenceof 667 species in the state (Appendix 1), of which17 have two well-differentiated subspecies with anallopatric or parapatric local distribution (Tables 3 and4). The five families with the highest number of speciesare the Thamnophilidae (61 species), Tyrannidae (61),Thraupidae (41), Accipitridae (29), and Furnariidae (26)which together account for 32.6% of the total numberof species recor<strong>de</strong>d in the state (Appendix 1). The nonpasserinesare represented by 300 species, and thepasserines, by 367 species. In the case of the passerines,247 species are sub-oscines (Tyranni), while the other120 species are oscines (Passeri).The occurrence of most (79.3%, n = 529) of thespecies recor<strong>de</strong>d for <strong>Acre</strong> has been confirmed by thecollection of voucher specimens (Appendix 1). Themajority of these specimens (84.9%, n = 4045) are<strong>de</strong>posited at MPEG, and most of the others (11.7%,n = 558) at the MZUSP. The remaining specimens –approximately 3.5% – are found in other museums inBrazil and abroad (Appendix 1).A total of 113 localities were compiled for the aviantaxa of <strong>Acre</strong> (Guilherme 2009, Figure 3). At six of thesesites, more than 300 species have been recor<strong>de</strong>d (Figure 3).In the case of 22 species, the data from <strong>Acre</strong>represent the only records for Brazil (Appendix 1). Thesecondary list (Appendix 2) was prepared based on the<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

400Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilhermeunconfirmed records of occurrence (41 species) andthe i<strong>de</strong>ntification of the species of probable occurrence(n = 49) in the state. As Hylophilus pectoralis (Guilherme& Dantas 2011) and Turdus nudigenis (Aleixo &Guilherme 2010) were, respectively, misi<strong>de</strong>ntified andmistyped, they have been exclu<strong>de</strong>d from the list of birdsof <strong>Acre</strong> presented here (Appendix 2). The cumulativenumber of species recor<strong>de</strong>d in the state since the firstpublication in the 1950s until the end of this study isshown in Figure 4.FIGURE 3. Localities where birds were collected and surveyed in the state of <strong>Acre</strong> between 1951 and 2011. Dot size corresponds to the number ofspecies recor<strong>de</strong>d at each locality as shown in the legend.FIGURE 4. Cumulative number of bird species recor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong> between 1951 and 2011.<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme401The vast majority of the 667 species recor<strong>de</strong>d for thestate – 602 (90,2%) – were classified as resi<strong>de</strong>nts, whereasfive (Bubulcus ibis, Geranoaetus albicaudatus, Caracaraplancus, Vanellus chilensis, and Athene cunicularia) wereconsi<strong>de</strong>red to be inva<strong>de</strong>rs, and another five as introducedspecies (Columba livia, Passer <strong>do</strong>mesticus, Sicalis flaveola,Sporophila maximiliani, and Estrilda astrild; Guilherme2000, 2011). The last species has adapted well to theregion (Silva 2004), and all introduced species nowreproduce in the wild in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>ntly.A total of 64 migratory species were i<strong>de</strong>ntified, ofwhich almost half 46.8% (n = 30) are Nearctic migrants,whereas 23.4% (n = 15) are consi<strong>de</strong>red to be intratropicalmigrants, and 29.6% (n = 19) austral migrants. Twospecies – Phoenicoparrus jamesi (Guilherme et al. 2005)and Heliomaster furcifer – were consi<strong>de</strong>red to be vagrants(Appendix 1).En<strong>de</strong>mic species<strong>Acre</strong> is located within the Inambari center ofen<strong>de</strong>mism (Haffer 1978; Cracraft 1985; Silva et al.2005b). Of the 57 taxa listed as en<strong>de</strong>mic to this centerby Cracraft (1985) and the 45 listed by Haffer (1978),41 were recor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong> (Appendix 1). The speciesO<strong>do</strong>ntophorus stellatus, Phaethornis phillipii, Pteroglossusbeauharnaesii, Simoxenops ucayalae, Hemitriccusflammulatus, and Ramphotrigon fuscicauda are not listedas en<strong>de</strong>mic in Appendix 1 because subsequent studies (see<strong>de</strong>l Hoyo 1994, 1999, 2002, 2003, 2004; Perlo 2009)have exten<strong>de</strong>d their known ranges beyond the limits ofthe Inambari center. However, four species were ad<strong>de</strong>dto this list, including three more recently <strong>de</strong>scribed taxa(Nannopsittaca dachilleae, Thamnophilus divisorius andCnipo<strong>de</strong>ctes superrufus) and one (Hypocnemis subflava) thathas been raised to full species status. Therefore, currently41 Inambari en<strong>de</strong>mic species are known to occur in <strong>Acre</strong>(Appendix 1).Endangered speciesNone of the native species recor<strong>de</strong>d in the presentstudy is inclu<strong>de</strong>d in the Brazilian list of bird speciesthreatened with extinction (Macha<strong>do</strong> et al. 2008). Onthe other hand, Sporophila maximiliani, which wasintroduced into the state by bird fanciers, and is nowfound naturally in the wild, is the only species listedas endangered by Macha<strong>do</strong> et al. (2008). However, theIUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)red list inclu<strong>de</strong>s 10 species resi<strong>de</strong>nt in <strong>Acre</strong> in the nearthreatened (NT) category – Harpia harpyja, Morphnusguianensis, Primolius couloni, Nannopsittaca dachilleae,Formicarius rufifrons, Grallaria elu<strong>de</strong>ns, Synallaxis cherriei,Simoxenops ucayalae, Conothraupis speculigera, and Cacicuskoepckeae.HabitatsMost (77.8%) of the bird species recor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong>are found in the <strong>de</strong>nse or open terra firme rainforest, withpalms and/or bamboo (Appendix 1). With the exceptionof a small proportion of species that are restricted tobamboo forest (Appendix 1), all other forest speciesrecor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong> are associated with forests where palmsare present. Approximately 12.9% of the recor<strong>de</strong>d speciesare associated with aquatic environments, such as várzeaswamp forest, riverbank habitats, creeks, reservoirs, lakes,and the sandy beaches formed by mean<strong>de</strong>ring riversduring the dry season (Appendix 1).A small, but nevertheless important, proportion ofthe species (2.1%) is strictly associated with the vegetationthat grows on sandy soils, that is, the campinas andcampinaranas (Appendix 1). These habitats are located onlyin the extreme west of the state. Of all bird species associatedwith this type of habitat in <strong>Acre</strong>, at least nine (Patagioenasspeciosa, Polytmus theresiae, Dendrocolaptes certhiapolyzonus, Formicivora grisea, Schiffornis amazona, Neopipocinamomea, Xenopipo atronitens, Cnemotriccus fuscatusduidae, and Tachyphonus phoenicius) can be consi<strong>de</strong>redto be restricted to these habitats, and at least a furthertwelve (Crypturellus strigulosus, Topaza pyra, Fre<strong>de</strong>rickenaunduligera, Heterocercus linteatus, Machaeropterus striolatus,Manacus manacus, Hemitriccus minimus, Hemitriccusgriseipectus, Lophotriccus vitiosus, Poecilotriccus latirostris,Ramphotrigon ruficauda, and Attila citriniventris) arepartially restricted to them (Guilherme 2009, Guilherme& Borges, 2011, Guilherme & Aleixo, unpubl. data).Distribution patternsThe majority (79%) of the 667 species of birds foundin <strong>Acre</strong> occur in both of its sub-regions (separated by thePurus River), and hence throughout the state (Appendix1). A further 16% were recor<strong>de</strong>d only in the centralwesternsub-region of the state (west of the Purus), and5% only in its eastern portion (east of the Purus). Noneof the species are restricted to the central portion of thestate - the intermediate region between the Juruá andPurus rivers.At least five pairs of purported sister taxa werei<strong>de</strong>ntified with a distribution pattern consistent withclassic allopatry (Table 1). In all these cases, one or otherof each pair of taxa was found in different areas of thestate, e.g., Crypturellus undulatus undulatus/yapura andLepi<strong>do</strong>thrix coronata coronata/exquisita.A total of 15 sets of parapatric purported sistertaxa were i<strong>de</strong>ntified during this study, encompassing30 taxa, 26 of which are currently treated as subspecies(Table 2). In most cases, one of the parapatric taxa iswi<strong>de</strong>ly distributed in <strong>Acre</strong>, whereas the other has a morerestricted range (Table 2, Figure 5).<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

402Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson GuilhermeTABLE 1. Sub-areas in the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> inhabited by allopatric pairs of diagnosable purported sister / closely related avian taxa.The Central-Eastern and Central-Western areas roughly correspond to the main river basins in the state and are separated by the Purus River.Taxon Central-Eastern Central-WesternCrypturellus undulatus undulatusXC. u. yapura XThrenetes leucurus cervinicaudaT. l. rufigastra XXMyrmothera campanisona minorM. c. cf. mo<strong>de</strong>sta XXCnemotriccus fuscatus duidaeC. f. cf. beniensis XXLepi<strong>do</strong>thrix coronata coronataL. c. exquisita XXTABLE 2. Sub-areas in the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> inhabited by parapatric pairs of diagnosable purported sister / closely related avian taxa. TheCentral-Eastern and Central-Western areas roughly correspond to the main river basins in the state and are separated by the Purus River.Taxon Central-Eastern Central-WesternRupornis magnirostris cf. magnirostris* X XR. m. occiduus XBrotogeris cyanoptera cyanoptera* X XB. c. beniensis XThalurania furcata boliviana* X XT. f. cf. jelskii XMomotus momota simplexM. m. cf. nattereri* X XXGalbula <strong>de</strong>a amazonumG. d. phainopepla XXCapito auratus orosaeC. a. insperatus X XXPteroglossus castanotis australisP. c. castanotis* X XXThamnophilus aethiops juruanus* X XT. a. kapouni* X X<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme403Taxon Central-Eastern Central-WesternHypocnemis peruviana* X XHypocnemis subflavaXGlyphorynchus spirurus castelnaudii* X XG. s. albigularis XDendrocincla fuliginosa neglectaD. f. atrirostris* X XXDendrocolaptes certhia juruanus* X XD. c. polyzonus XXiphorhynchus ocellatus* X XXiphorhynchus chunchotamboXPipra filicaudaPipra fasciicauda* X XXArremon taciturnus taciturnus* X XArremon t. cf. nigrirostrisX* Taxon with a wi<strong>de</strong> distribution within the stateFIGURE 5. Geographic distribution of the parapatric taxa Dendrocincla fuliginosa neglecta and D. f. atrirostris in western <strong>Acre</strong> and the proposed zoneof secondary contact (see text). The arrows point from the core to the periphery of the ranges of the respective taxa.<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

404Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson GuilhermeContact and hybridization zonesTwo contact zones were i<strong>de</strong>ntified within the studyarea (<strong>Acre</strong>) based on the distribution of parapatric taxa(Table 2). I have <strong>de</strong>noted these zones as the (a) westerncontact zone and (b) eastern contact zone (Figures 5, 6,and 7). The western contact zone is based on the presenceof the following sister taxa – Pipra filicauda/P. fasciicauda(Figure 6), Dendrocincla fuliginosa neglecta/D. f. atrirostris(Figure 5), and Pteroglossus castanotis castanotis/P. c.australis (Guilherme 2009). The eastern zone is <strong>de</strong>finedby the occurrence of Xiphorhynchus chunchotambo/ocellatus, Hypocnemis subflava/peruviana (Figure 7), andGlyphorhynchus spirurus castelnaudii/G. s. albigularis(Guilherme 2009).Two possible hybridization zones were i<strong>de</strong>ntifiedwithin the study area, coinciding with the contact zones.The western hybridization zone is <strong>de</strong>fined on the basis ofthe presence of specimens with intermediate characteristicsbetween Pteroglossus castanotis castanotis/P. c. australisand Dendrocolaptes certhia juruanus/D. c. polyzonus,whereas the eastern zone is characterized by the presenceof morphologically intermediate specimens betweenBrotogeris cyanoptera cyanoptera/B. c. beniensis and Momotusmomota cf. nattereri/M. m. simplex (Guilherme 2009).DISCUSSIONBird diversity in <strong>Acre</strong>The large number of bird species recor<strong>de</strong>d in theBrazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong> further emphasizes the biologicaldiversity of southwestern Amazonia (Haffer 1990). Infact, the number of species recor<strong>de</strong>d for <strong>Acre</strong> – 667 –represents more than half of the total recor<strong>de</strong>d for thewhole of the Amazon basin (Marini & Garcia, 2005;Mittermeier et al. 2003), and if only the fauna of thesouthern basin (south of the Solimões/Amazon channel)is consi<strong>de</strong>red (Stotz et al. 1996), 74.4% of the specieswere recor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong>.The avifauna of <strong>Acre</strong> is composed primarily ofresi<strong>de</strong>nt species, but also inclu<strong>de</strong>s migrants and inva<strong>de</strong>rs.Five of the nine new species ad<strong>de</strong>d to the list of Brazilianbirds since 2005 were recor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong> (Guilherme et al.2005, Guilherme & Aleixo 2008, Aleixo et al. 2008, Regoet al. 2009, Zimmer et al. 2010, CBRO 2011). Anotherspecies – Cacicus koepckeae – should also be ad<strong>de</strong>d to thislist, based on the recent record from the Chandless River(Buzetti 2008). Of the 1832 bird species known to occurin Brazil (CBRO, 2011), 22 have been recor<strong>de</strong>d only in<strong>Acre</strong> (Appendix 1), which testifies to the singularity ofthis state. <strong>Acre</strong> is located entirely within the Inambaricenter of en<strong>de</strong>mism, the largest such area in the lowlandsof the southern Amazon basin (Silva et al. 2005b).According to Cracraft (1985), the geographic rangesof the 57 bird taxa en<strong>de</strong>mic to the southwestern Amazonbasin <strong>de</strong>fine the limits of the Inambari center. Almostthree quarters (73.6%) of these en<strong>de</strong>mic taxa have beenrecor<strong>de</strong>d in <strong>Acre</strong>, with four new species (all <strong>de</strong>scribed since1985) being ad<strong>de</strong>d to the list subsequently (Appendix 1).<strong>Acre</strong> can be consi<strong>de</strong>red to be an excellent sample of theInambari center, given that it covers only 12% of its area,but contains more that 70% of its en<strong>de</strong>mic species. Giventhis, <strong>Acre</strong> is an excellent natural laboratory for the studyof historic biogeography.The migratory species were recor<strong>de</strong>d in both of thegeographic sub-regions (Appendix 1). However, some ofthe species arriving from south-central South Americawere only observed in eastern <strong>Acre</strong> (Appendix 1). Australand intratropical migrants such as Myiopagis viridicata,Tyrannus albogularis, Casiornis rufus, and Turdusamaurochalinus, arrived in the state from the southeast(e.g., Bolivian Chaco), where they breed (Davis 1993;Jahn et al. 2002, Appendix 1). Some migratory species,in particular tyrannids, tend to occupy the forest edges,secondary vegetation, and open areas (Chesser 1997). Asthe forest cover of easternmost <strong>Acre</strong> has been extensivelydisturbed, the resulting open and regenerating habitatscontribute to an increase in the probability of recordingother forest edge species such as Micrococcyx cinereus,Contopus cinereus, and Elaenia flavogaster (Appendix 1). Itseems likely that the occurrence of these species will alsobe confirmed for the central-western sub-region of thestate as new surveys are carried out in these areas duringthe migration season.A group of species, previously known only from thefoothills of the An<strong>de</strong>s and lowlands in Peru and Bolivia,was recor<strong>de</strong>d in the central eastern sub-region of <strong>Acre</strong>.For some species, such as Picumnus subtilis, Xiphorhynchuschunchotambo, and Cacicus koepckeae, these records<strong>do</strong> not represent either migrations or recent shifts indistribution, but rather, these species are resi<strong>de</strong>nts thathad simply not been recor<strong>de</strong>d previously, due to thelack of surveys in the area adjacent to the bor<strong>de</strong>rs withPeru and Bolivia. Other species, such as Conothraupisspeculigera and Pseu<strong>do</strong>colopteryx acutipennis neverthelessappear to migrate from the Pacific slope and An<strong>de</strong>s to thelowlands of Amazonia.Vagrancy also plays a role in the <strong>Acre</strong> avifauna.Phoenicoparrus jamesi, which is typical of the salt lakesof the An<strong>de</strong>an altiplano, was observed in <strong>Acre</strong> on a singleoccasion, and was consi<strong>de</strong>red to be an acci<strong>de</strong>ntal visitorby Guilherme et al. (2005). The nearest record of thisspecies is from the Manu National Park in southwesternPeru, at an altitu<strong>de</strong> of 350 m asl, where it was alsoconsi<strong>de</strong>red to be an vagrant (Walker et al. 2006), giventhat this lowland area is equally distant from the naturaldistribution of the species (<strong>de</strong>l Hoyo et al. 1992). Anotherspecies consi<strong>de</strong>red to be a vagrant here is Heliomaster<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme405FIGURE 6. Geographic distributions of Pipra filicauda and P. fasciicauda according to Natureserve (2007). The arrows point from the core to theperiphery of the ranges of the respective species. The red triangles and black <strong>do</strong>ts indicate the parapatric occurrence, respectively, of Pipra filicauda andP. fasciicauda in western <strong>Acre</strong>.FIGURE 7. Geographic distribution of the parapatric species Hypocnemis peruviana and H. subflava in eastern <strong>Acre</strong> showing the estimated “secondarycontact zone”. The arrows point from the core to the periphery of the ranges of the respective species<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

406Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilhermefurcifer. The only record of this species for <strong>Acre</strong> is a singlespecimen (ZUEC – 1565) <strong>de</strong>posited in the ornithologicalcollection of zoology museum at UNICAMP (Appendix1). This specimen was found <strong>de</strong>ad on the Campus of theFe<strong>de</strong>ral University of <strong>Acre</strong> by herpetologist Adão JoséCar<strong>do</strong>so, in February 1988. The species is consi<strong>de</strong>redto be a vagrant because its known range is restricted tosouthern central South America (<strong>de</strong>l Hoyo et al. 1999).Whereas this species might be consi<strong>de</strong>red an austral orintratropical migrant, the date on which the specimen wasfound (during the austral summer) is inconsistent withthis classification. Another possibility is that the speciesis resi<strong>de</strong>nt in <strong>Acre</strong>, but is rare and occurs at a low <strong>de</strong>nsityin the region. However, the lack of records from northernBolivia, eastern Peru, and other parts of <strong>Acre</strong>, togetherwith the single records available from Leticia (southeastColombia) and Napo, in northeastern Ecua<strong>do</strong>r (<strong>de</strong>l Hoyoet al., 1999) reinforce the conclusion that the species is asporadic vagrant in the Amazon basin.Invasive species were concentrated primarily inthe eastern extreme of the state, presumably due to itsrelatively high human population <strong>de</strong>nsity and greater areaof altered habitats. This part of <strong>Acre</strong> is connected to theneighboring state of Rondônia by a major highway alongwhich many large cattle ranches occur, which explains whysome species, such as Geranoaetus albicaudatus, Caracaraplancus, Vanellus chilensis, and Athene cunicularia, beganto colonize the state from the east, even though they havenow reached its western portion, towards Cruzeiro <strong>do</strong> Sul,as well as areas in the southeast, in the direction of thetowns of Brasiléia and Assis Brasil, on the bor<strong>de</strong>r withBolivia and Peru. A similar situation has arisen in the caseof species that have escaped from captivity, such as Estrildaastrild (see Silva 2004), or that have been released intourban environments on purpose, such as Sicalis flaveolaand Passer <strong>do</strong>mesticus (Guilherme 2000, 2011). Thesespecies were first recor<strong>de</strong>d in the state capital (Rio Branco),but have since colonized practically all the urban centerslocated along the main highways that cross the state.Few regional ornithological studies are availablethat can be used for systematic comparisons with theinventory presented here, although similar studies havebeen conducted in the Brazilian state of Roraima andthe Bolivian <strong>de</strong>partment of Pan<strong>do</strong>. Roraima is the onlyBrazilian state localized within the Amazon basin whichhas had its avifauna surveyed systematically – includinghistorical records – in recent years (Santos 2005; Naka etal. 2006). Santos (2005) and Naka et al (2006) recor<strong>de</strong>d741 bird species in Roraima, a total 10.3% higher thanwhat I am reporting here for <strong>Acre</strong>. There are two mainfactors that may account for this difference. One is thefact that Roraima’s area is almost a third (32%) largerthan that of <strong>Acre</strong>, and the other is the fact that Roraimais a more heterogeneous region, with a number of typesof habitat not found in <strong>Acre</strong>, such as dry and montaneforests, tepuis, and savannas (Santos 2005; Nakaet al. 2006).By contrast, the species richness recor<strong>de</strong>d here for<strong>Acre</strong> was 25.5% higher than that reported by Remsenand Traylor (1989) for Pan<strong>do</strong>, in Bolivia, although therewas a similarity of 91.6% between the species lists ofthe two territories, which is a result of their geographicand ecological similarities, including the same habitatsand similar altitu<strong>de</strong>s (Parker & Remsen 1997; Tobias &Sed<strong>do</strong>n 2007). The larger number of species recor<strong>de</strong>d for<strong>Acre</strong> may be related to sampling effort, but also the factthat this state is more than twice the size of its Boliviancounterpart (164,221 km 2 vs 61,331 km 2 ).The number of bird species known to occur in <strong>Acre</strong>more than <strong>do</strong>ubled over the past two <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s, which reflectsthe increase in sampling effort during this period (Figure 4).However, whereas the number of species already recor<strong>de</strong>dfor the state is substantial, it seems likely that the specieslist will still grow over the next few years. This conclusionis partly supported by some of the species that have beenrecor<strong>de</strong>d in neighboring areas, such as southwesternAmazonas and the lowlands of Peru and Bolivia, but haveyet to be confirmed for <strong>Acre</strong> (Appendix 2).Recent surveys in <strong>Acre</strong> have recor<strong>de</strong>d a numberof species that were previously known only for thePeruvian and Bolivian Amazon basin. The records ofXiphorhynchus chunchotambo, Pachyramphus xanthogenys,Picumnus subtilis, Glyphorhynchus spirurus albigularis,and Poecilotriccus albifacies presented here were the firstfor Brazil (Guilherme & Aleixo, 2008, Aleixo et al.2008, Rego et al. 2009, Guilherme 2009, Zimmer et al.2010). Some of these species were previously known onlyfrom the Peruvian and Bolivian An<strong>de</strong>an region at low tomo<strong>de</strong>rate elevations and have only recently been recor<strong>de</strong>din the adjacent lowlands of the Brazilian Amazon basin(Guilherme & Aleixo 2008, Aleixo et al. 2008, Rego et al.2009, Aleixo & Guilherme 2010, Zimmer et al. 2010).One other example is Chrysolampis mosquitus, which wasrecor<strong>de</strong>d from the upper Purus in 2007 (Guilherme &Dantas 2008, Guilherme & Dantas 2011a); previously,this species had been recor<strong>de</strong>d two years earlier in Bolivia(Tobias & Sed<strong>do</strong>n 2007).Overall, the sum of the confirmed species (Appendix1) with those of likely occurrence (Appendix 2) indicatesa potential count of 757 bird species for the Brazilian stateof <strong>Acre</strong>. If this prediction is confirmed even partially, <strong>Acre</strong>would have one of the richest avifaunas of any Brazilianstate, <strong>de</strong>spite its relative reduced area.Zoogeography of birds in <strong>Acre</strong><strong>Acre</strong> resembles a butterfly wing in shape, with aconstriction in the center of two roun<strong>de</strong>d lobes (Figure2), with its primary axis in an east-west orientation,rather than north-south. This means that the distribution<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012

Birds of the Brazilian state of <strong>Acre</strong>: diversity, zoogeography, and conservationEdson Guilherme407of local species is best un<strong>de</strong>rstood in an east-west, ratherthan a north-south dimension, with the Purus Riverforming the principal division within the state. The Purusdivi<strong>de</strong>s <strong>Acre</strong> into two main portions, an eastern portionon its right margin, and western portion to its left margin(Figure 2).Of the resi<strong>de</strong>nt forest taxa in <strong>Acre</strong>, almost 80% arewi<strong>de</strong>ly distributed within the state, being found in bothits eastern and western portions. Among other things, thisreflects the mostly low-lying terrain (except in the westernextreme) and relatively homogeneous habitats foundthroughout most of the state. This low species turnoverwould be expected in the absence of major physicalbarriers, such as rivers or mountains, capable of limitingthe dispersal of most taxa. However, some taxa onlyoccur in one of the state’s two sub-regions, although thisdistribution pattern appears not related to the presenceof the two main rivers that cross the state, the Purus andthe Juruá. This may be primarily due to the fact that thesehighly mean<strong>de</strong>ring rivers arise in lowland Amazonia, andso, taxa can cross them often more easily than they wouldrivers whose headwaters are in unsuitable habitat (such asdry country or mountains). Genetic studies of primates(Peres et al. 1996), ro<strong>de</strong>nts (Patton et al. 1994; Patton andSilva 1998), birds (Aleixo 2004, Fernan<strong>de</strong>s et al. 2012),and amphibians (Gascon et al. 1998) have all confirmedthat the Juruá is an ineffective zoogeographic barrier forthese groups.Other factors may nevertheless influence thedistribution of different taxa in southwestern Amazonia,including interspecific competition, edaphic conditionsand habitat characteristics (Tuomisto et al. 1995, 2003;Daly & Silveira, 2002; Roig & Martini, 2002; Silveiraet al. 2002). A closer examination of the geographicdistribution of birds within one of the sub-regions(Appendix 1) reveals that the pattern observed in <strong>Acre</strong> isrepeated on the Peruvian si<strong>de</strong> of the bor<strong>de</strong>r. Species suchas Phlegopsis erythroptera, Thamnomanes saturninus, Attilacitriniventris, Pipra filicauda, and Dixiphia pipra havealso been recor<strong>de</strong>d only in northeast Peru (Schulenberget al. 2007). Similarly, Poecilotriccus albifacies, Cnipo<strong>de</strong>ctessuperrufus, and Micrococcyx cinereus, which were onlyfound in eastern <strong>Acre</strong> (Appendix 1), were also found onlyin adjacent southeastern Peru (Schulenberg et al. 2007).A similar pattern has also been recor<strong>de</strong>d for palms(Arecaceae) in <strong>Acre</strong>. Some species, such as Wettiniaaugusta, Syagrus smithii, Socratea salazarii, Iriartellastenocarpa, Hyospathe elegans, Dyctyocaryum ptarianum,Bactris riparia, and Astrocaryum faranae, are foun<strong>do</strong>nly in the western sub-region of <strong>Acre</strong> (Lorenzi et al.2004). Other species, such as Astrocaryum aculeatum,Astrocaryum murumuru, and Bactris elegans are restrictedto the eastern part of the state (Lorenzi et al. 2004). Eventhough practically all these species of palm also occurin areas adjacent to <strong>Acre</strong>, their east-west distributionwithin the state is similar to that observed in some birdspecies (Appendix 1). Some of these palm species arealso restricted to specific environments, such as plateaus,swamps, campinas, and campinaranas. This distributionpattern in <strong>Acre</strong> may be a reflection of the sedimentaryhistory of the Marañon–Ucayali–<strong>Acre</strong> basin, to the west,and the Madre <strong>de</strong> Dios basin, to the east. In the westernpart of the state, relatively ancient formations (e.g.,Fm Moa, Rio Azul, Divisor and Cruzeiro <strong>do</strong> Sul) wereexposed by the uplift of the An<strong>de</strong>s, and contrast withthe more recent Cenozoic formations in the east partsof the state, e.g., Fm Solimões and Fm Madre <strong>de</strong> Dios(Milani & Thomaz Filho, 2000, Campbell et al., 2006).In western <strong>Acre</strong>, the topography and variations in thecomposition of the soil have played an important role inthe formation of distinct ecosystems, which may certainlyhelp to explain the higher number of species of palms andbirds (and probably others groups of organisms) restrictedto western <strong>Acre</strong> (Lorenzi et al. 2004, Guilherme, 2009).For most of the species restricted to one of the subregions,<strong>Acre</strong> and the adjacent lowlands of Peru representthe southwestern extreme of their distribution in theAmazon basin. Species such as Thamnomanes saturninus,Pipra filicauda (Figure 6), and Dixiphia pipra are wi<strong>de</strong>lydistributed in northern Amazonia, ranging south as faras the southwestern extreme of the Amazon lowlands(Ridgely & Tu<strong>do</strong>r, 2009). There are exceptions, however,such as Thamnophilus divisorius, which is en<strong>de</strong>mic towestern <strong>Acre</strong> and northeastern Peru. The distribution ofthis species is associated with an area of mo<strong>de</strong>rate altitu<strong>de</strong>,the submontane forests of the Serra <strong>do</strong> Divisor range.Many of the taxa restricted to the eastern sub-region of<strong>Acre</strong> are associated with bamboo forests (e.g., Picumnussubtilis, Cnipo<strong>de</strong>ctes superrufus, and Poecilotriccus albifacies)or <strong>de</strong>nse rainforest (e.g., Lepi<strong>do</strong>thrix coronata exquisita).Eastern <strong>Acre</strong> encompasses the greatest concentration ofthese habitats than the western portion of the state. Thissuggests that habitat-related environmental gradientsmay play a more important role in the distribution ofthe species in eastern <strong>Acre</strong> than the mere presence of aphysical barrier such as the Purus River. Other taxarestricted to eastern <strong>Acre</strong>, such as Crypturellus undulatusundulatus, Antrostomus sericocaudatus, and Herpsilochmusrufimaginatus, are more wi<strong>de</strong>ly distributed in the Amazonbasin, although this may represent the southwesternextreme of their distribution.Allopatric/parapatric rangesWhereas five pairs of purported sister taxa appear tohave an allopatric distribution in <strong>Acre</strong> (Table 1), it seemslikely that further ornithological surveys may confirmthat these taxa are actually parapatric in the state, and thattheir apparent allopatric distribution is merely a samplingartifact. A common feature of the taxa consi<strong>de</strong>red to be<strong>Revista</strong> <strong>Brasileira</strong> <strong>de</strong> <strong>Ornitologia</strong>, 20(4), 2012