(Nestor notabilis) Husbandry Manual - Kea Conservation Trust

(Nestor notabilis) Husbandry Manual - Kea Conservation Trust

(Nestor notabilis) Husbandry Manual - Kea Conservation Trust

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1<br />

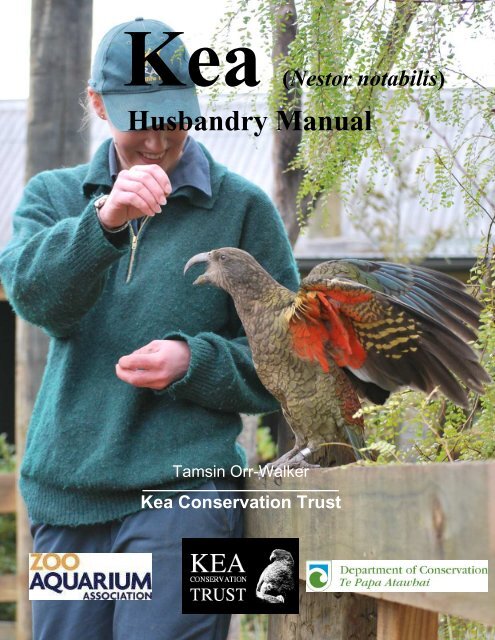

<strong>Kea</strong> (<strong>Nestor</strong> <strong>notabilis</strong>)<br />

<strong>Husbandry</strong> <strong>Manual</strong><br />

Tamsin Orr-Walker<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong><br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

2<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

3<br />

Prepared by<br />

Tamsin Orr-Walker<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong><br />

August 2010<br />

This husbandry manual sets new standards and expectations for the captive<br />

husbandry of kea in New Zealand. The minimum standards throughout this<br />

document are designed to provide the minimum welfare guidelines for captive<br />

kea. It is hoped that all kea holders will strive for the best practice standards<br />

outlined here and even better, exceed them.<br />

This husbandry manual has been the subject of extensive consultation with<br />

captive holders, experienced vet's, the Captive Management Coordinator (CMC)<br />

and industry participants. This husbandry manual is considered best practise by<br />

the KCT and ZAA and in line with the WAZACS. It has been submitted to the<br />

Department of <strong>Conservation</strong> for formal approval in terms of the Department of<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> Captive Management Standard Operating Procedure.<br />

This document is dedicated to Ariki, Hopara and Sweety (Nauhea) and for all<br />

other kea in captive facilities throughout New Zealand; here’s to a brighter future<br />

for you all!<br />

“the critical role of zoos and aquariums within conservation is more<br />

important than ever. Zoos and aquariums are in a unique position: that of<br />

providing conservation in a genuinely integrated way. For the young people of the<br />

world’s cities, zoos and aquariums are often the first contact with nature and so<br />

you are the incubator of the conservationists of tomorrow.”<br />

Achim Steiner - Director General, IUCN (WAZACS, 2005)<br />

Ariki during a training session, spreading<br />

his wings during a health check.<br />

Photo credit: T Orr-Walker 2003<br />

Cover Photo:<br />

Alyssa Salton and Silver during a relaxed training session in Orana Parks<br />

walk through <strong>Kea</strong> enclosure. Photo credit: Orana Wildlife Park<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

4<br />

Contents<br />

1.0 PREFACE ............................................................................8<br />

2.0 INTRODUCTION..................................................................8<br />

2.1 Taxonomy ................................................................................. 9<br />

2.2 <strong>Conservation</strong> Status.................................................................. 9<br />

2.2.1 Population Estimates ..................................................................9<br />

2.3 Captive Management Coordinator and Contacts...................... 9<br />

2.4 Captive Population.................................................................. 10<br />

3.0 NATURAL HISTORY..........................................................12<br />

3.1 Introduction ............................................................................. 12<br />

3.2 Biodata.................................................................................... 12<br />

3.3 Distribution, habitat and home range ...................................... 13<br />

3.4 Habits, movements and social structure ................................. 13<br />

3.5 Feeding behaviour .................................................................. 14<br />

3.6 Reproduction........................................................................... 15<br />

3.7 Protected species’ role in ecosystem...................................... 15<br />

3.8 Threats in the wild................................................................... 16<br />

3.8.1 Human Induced threats ............................................................ 16<br />

3.8.2 Predation .................................................................................. 17<br />

4.0 CAPTIVE HUSBANDRY.....................................................18<br />

4.1 Housing/Environment Standards ............................................ 19<br />

4.1.1 Introduction............................................................................... 19<br />

4.1.2 Enclosure Types ....................................................................... 19<br />

4.1.3 Size........................................................................................... 22<br />

4.1.4 Materials for housing ................................................................ 24<br />

4.1.5 Shelter/screening/barriers......................................................... 25<br />

4.1.6 Water ........................................................................................ 26<br />

4.1.7 Furnishings, vegetation and substrates .................................... 27<br />

4.1.8 Multi-species Exhibits ............................................................... 28<br />

4.1.9 Enclosure Siting........................................................................ 30<br />

4.1.10 Enclosure Security.................................................................. 31<br />

Minimum Standard 4.1 - Housing Environment Standards .... 31<br />

Best Practice 4.1 - Housing Environment Standards.............. 34<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

5<br />

4.2 Enrichment.............................................................................. 35<br />

4.2.1 Introduction............................................................................... 35<br />

4.2.2 Behavioural needs .................................................................... 36<br />

4.2.3 Enrichment programme ............................................................ 37<br />

4.2.4 Additional Links......................................................................... 39<br />

Minimum Standard 4.2 - Enrichment......................................... 39<br />

Best Practice 4.2 - Behavioural Enrichment............................. 40<br />

4.3 Training and conditioning........................................................ 41<br />

4.3.1 Introduction............................................................................... 41<br />

4.3.2 Relevance................................................................................. 41<br />

4.3.3 Methods.................................................................................... 41<br />

4.3.4 Trainers..................................................................................... 42<br />

Minimum Standard 4.3 - Training and Conditioning................ 42<br />

Best Practice 4.3 – Training and Conditioning ........................ 43<br />

4.4 Social Structure....................................................................... 43<br />

4.4.1 Introduction............................................................................... 43<br />

4.4.2 Life stages and gender requirements ....................................... 44<br />

4.4.3 Development of new social groupings ...................................... 44<br />

Minimum Standard 4.4 – Social Structure ................................ 45<br />

Best Practice 4.4 – Social Structure.......................................... 46<br />

4.5 Health Care Standards ........................................................... 46<br />

4.5.1 Environmental hygiene and cleaning ........................................ 46<br />

4.5.2 Health problems........................................................................ 47<br />

4.5.3 Preventative measures ............................................................. 51<br />

4.5.4 Treatments and Veterinary Procedures .................................... 52<br />

4.5.5 Dead specimens ....................................................................... 52<br />

4.5.6 Quarantine procedures ............................................................. 53<br />

4.5.7 Handling/physical restraint........................................................ 53<br />

4.5.8 Transport Requirements ........................................................... 54<br />

4.5.9 Transfer and quarantine ........................................................... 55<br />

Minimum Standard 4.5 – Health Care Standards..................... 55<br />

Best Practice 4.5 – Health care Standards ............................... 57<br />

4.6 Feeding Standards.................................................................. 57<br />

4.6.1 Introduction............................................................................... 57<br />

4.6.2 Toxic Foods .............................................................................. 58<br />

4.6.3 Diets and supplements ............................................................. 59<br />

4.6.4 Presentation of food.................................................................. 60<br />

4.6.5 Seasonal/breeding changes in feeding requirements ............... 61<br />

4.6.6 Food Hygiene ........................................................................... 61<br />

Minimum Standard 4.6 – Feeding Standards ........................... 61<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

6<br />

Best Practice 4.6 – Feeding Standards..................................... 62<br />

4.7 Reproduction........................................................................... 62<br />

4.7.1 Introduction............................................................................... 63<br />

4.7.2 Forming new breeding pairs ..................................................... 65<br />

4.7.2 Nesting/breeding requirements................................................. 65<br />

4.7.3 Requirements and development of young ................................ 66<br />

4.7.4 Hand rearing Techniques.......................................................... 66<br />

4.7.5 Methods of controlling breeding................................................ 66<br />

4.7.6 Breeding recommendations...................................................... 67<br />

Minimum Standard 4.7 – Reproduction .................................... 67<br />

Best Practice Standard 4.7 – Reproduction ............................. 68<br />

5.0 IDENTIFICATION...............................................................69<br />

5.1 Introduction ............................................................................. 69<br />

5.2 Individual Identification............................................................ 69<br />

5.3 Sexing Methods ...................................................................... 70<br />

5.3.1 Morphological Sexing Method................................................... 70<br />

5.3.2 Behavioural Indicators for Sexing ............................................. 70<br />

5.3.3 DNA Feather Sexing................................................................. 71<br />

Minimum Standard 5 – Identification ........................................ 71<br />

Best Practice Standard 5 – Identification ................................. 72<br />

6.0 RECORD KEEPING...........................................................73<br />

6.1 Individual records.................................................................... 73<br />

6.2 End of breeding season reports.............................................. 73<br />

Minimum Standard 6 – Record Keeping ................................... 73<br />

7.0 Acknowledgments ..............................................................75<br />

9.0 Appendices.........................................................................80<br />

9.1 Appendix 1- Internal Audit Document ..................................... 81<br />

9.2 Appendix 2 – Important Links ................................................. 99<br />

9.3 Appendix 3 – List of Appropriate Enclosure Materials .......... 100<br />

9.4 Appendix 4 – Massey University (Huia) Wildlife Submission<br />

Form............................................................................................ 101<br />

9.5 Appendix 5 – Quarantine Protocol........................................ 102<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

7<br />

9.6 Appendix 6 – Example of diet and feeding regime (Franklin<br />

Zoo)............................................................................................. 103<br />

9.7 Appendix 7 - Hand raising techniques (Woolcock, 2000) ..... 104<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

8<br />

1.0 PREFACE<br />

The production of this husbandry manual has been supported by the <strong>Kea</strong><br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> (KCT), Zoo and Aquarium Association (ZAA) and Department<br />

of <strong>Conservation</strong> (DOC). Changes to this document require appropriate<br />

consultation with all stakeholders including the author, KCT, ZAA and DOC.<br />

This document is to be considered a living document and updated as required. It<br />

will be formally reviewed in 2012 and at five yearly intervals thereafter.<br />

2.0 INTRODUCTION<br />

This husbandry manual has been prepared for all holders of captive <strong>Kea</strong>, <strong>Nestor</strong><br />

<strong>notabilis</strong>. It reflects the collective experience of many individuals and<br />

organisations that have held kea in captivity nationally and internationally, and<br />

seeks to document current best practice in husbandry of captive kea. It also<br />

reflects the collective knowledge of researchers and field workers working directly<br />

with kea in-situ and as such aims to increase the standard of care the species<br />

receives in captivity.<br />

This manual also establishes clear minimum standards for some aspects of kea<br />

husbandry. These minimum standards have not been established with the<br />

purpose of eliminating all variation on how holders keep and care for kea (and/or<br />

present them for display). Rather, they are there to reassure all those with an<br />

interest in kea, including the captive management community, the Department of<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong>, <strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>, iwi groups, and the public of New<br />

Zealand, that the fundamental requirements of kea husbandry are being met by<br />

all holders. It is envisaged that fulfilment of minimum standards will be a staged<br />

process with all stakeholders working practically and in collaboration to ensure<br />

the best outcome for captive kea in New Zealand.<br />

Optimal standards are also provided for relevant sections and are in addition to<br />

the minimum standards.<br />

Consistent terminology is used throughout the document. Recommendations or<br />

guidelines are worded using ‘may’, ‘can’, ‘should try to’ etc, whereas requirements<br />

or minimum standards use ‘must’. A six monthly internal audit document can be<br />

found in Appendix 1. This aims to provide holders with a means of assessing<br />

minimum standards in regards their own kea. It also provides holders with a tool<br />

to help them focus on where they need to improve to come up to standard. This<br />

document will be used with other resources by DOC to assess permit approval.<br />

It is not the intention of this manual to reproduce material which has been<br />

published elsewhere. As such this manual should not be considered in isolation,<br />

but as part of a series of resources that lay out why and how we care for kea in<br />

captivity. All resources may be found on the <strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s website<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

9<br />

(www.keaconservation.co.nz). Resources available to download or access<br />

include papers and manuals on kea behaviour and enrichment and captive and<br />

wild research as well as a comprehensive bibliography on the species or related<br />

issues and links to other organisations involved in kea specific work. These links<br />

at the time of publication are as follows:<br />

• http://www.avianbibliography.org/kea.htm<br />

• http://bsweb.unl.edu/avcog/research/keapubs.htm<br />

• http://www.keaconservation.co.nz<br />

People with an interest in the husbandry of kea, especially those that care for kea<br />

on a daily basis, are encouraged to contact the Captive Management staff (see<br />

section 2.3) with suggestions and comments.<br />

2.1 Taxonomy<br />

Class: Aves<br />

Order: Psittaciformes<br />

Family: <strong>Nestor</strong>idae<br />

Species: <strong>Nestor</strong> <strong>notabilis</strong><br />

2.2 <strong>Conservation</strong> Status<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> are presently classified as ‘naturally uncommon” (Townsend et al., 2008) and<br />

as Vulnerable in the IUCN Red List (Birdlife International 2008).<br />

2.2.1 Population Estimates<br />

The current population status of <strong>Kea</strong> in the wild is poorly known. The lack of<br />

accurate population data is due to the difficulties in surveying and monitoring kea.<br />

The low density, marked seasonal and life stage variation and extremely rugged<br />

habitat of this species present a number of challenges to obtaining an accurate<br />

total population count (Elliot & Kemp, 2004).<br />

The most recent estimate of overall population size gives numbers of between<br />

1000-5000 individuals remaining (Anderson, 1986).<br />

Results of research into the effects of hunting and predation on kea by Elliot and<br />

Kemp (2004) suggest a marked increase in the risk of extinction over 100 years<br />

from 0.8% in the 1850’s versus 32% in 2004 and a lack of confidence in<br />

population stability.<br />

2.3 Captive Management Coordinator and Contacts<br />

DOC Lead Technical Support Officer (TSO) for kea<br />

Bruce McKinley<br />

bmckinlay@doc.govt.nz<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

10<br />

DOC Appointed Captive Management Coordinator<br />

Tony Pullar<br />

Dunedin,<br />

New Zealand<br />

Email: tpullar@es.co.nz<br />

Phone: +64 3 4738740<br />

ZAA <strong>Kea</strong> Contact<br />

Stephanie Behrens<br />

Zoo and Aquarium Association<br />

New Zealand Office<br />

Email: steph@zooaquarium.org.au<br />

Phone: +64 9 360 3807<br />

2.4 Captive Population<br />

As of March 2010 the known New Zealand captive kea population numbered 86<br />

birds (58.5 males, 27.5 females) held by 19 public facilities (14 of which are ZAA<br />

members) and 12 private holders. Age of captive population is shown in Fig 1 and<br />

founder representation in the current ZAA membership population is shown in Fig<br />

2 (Behrens, 2010).<br />

Figure 1: Age Pyramid for total living captive population<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

11<br />

Fig 2: ZAA member organisation founders. #45; 53; 80; 162; 170; 232; 320 and<br />

324 are still living although they are not genetically represented in the current<br />

captive population. It is thought founders #123 and #124 escaped. #6; 68; 78;<br />

114; 136; 140 and 172 are dead. Of the 12 living founders, 11 are male (seven<br />

with no genetic representation in the population) and one is female (also without<br />

genetic representation).<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

12<br />

3.0 NATURAL HISTORY<br />

3.1 Introduction<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> (<strong>Nestor</strong> <strong>notabilis</strong>), are a psittacine species endemic to New Zealand’s South<br />

Island alpine areas. They are the world’s only alpine parrot and as such are<br />

unique. <strong>Kea</strong>, along with the kaka (<strong>Nestor</strong> meridionalis) and kākāpo (Strigops<br />

habroptilus), are thought to together form the sole members of a distinct parrot<br />

family, <strong>Nestor</strong>idae, within the avian order Psittaciformes (parrots and cockatoos).<br />

It seems likely that the <strong>Nestor</strong>idae lineage diverged from that of other parrots<br />

some 80 million years ago, perhaps as a result of geographical isolation<br />

associated with the separation of 'Zealandia' (the precursor to New Zealand) from<br />

Gondwanaland (Christidis & Boles, 2008).<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> have been subject to an extended and unusual period of persecution in New<br />

Zealand which has resulted in a major decline in numbers and an uncertain<br />

present day status. <strong>Kea</strong> gained full protection under the Wildlife Act (1953) in<br />

1986. Prior to this they were hunted in a government bounty system up until 1971,<br />

which resulted in an estimated 150,000 killed.<br />

They are considered by scientists nationally and internationally, to be one of the<br />

most intelligent bird species. They are also considered the ‘Clown of the<br />

Mountains’ by our overseas tourists and do much to bring life and colour to the<br />

Southern Alps. They are of both national and local significance to the peoples of<br />

New Zealand and are considered to be " the guardians of the mountains" by the<br />

Waitaha Maori (Temple, 1996).<br />

Maori gave the species their common name, kea, describing the sound of their<br />

call. <strong>Kea</strong> were considered guardians of the mountains for the Waitaha Maori<br />

during their search for Pounamu (greenstone) (Temple, 1996). The keas species<br />

name, <strong>Nestor</strong> is from Greek mythology. <strong>Nestor</strong> was said to be a wise old<br />

counsellor to the Greeks at Troy. Notabilis (latin), means, ‘that worthy of note’.<br />

3.2 Biodata<br />

Adult weights and measurements vary significantly between individuals<br />

particularly in beak length. However males are generally larger and heavier than<br />

females (Fijn, 2003). A combination of weight, skull and beak measurements can<br />

be used to identify probability of gender in kea as follows:<br />

Gender *Weight range Body Beak Skull<br />

length length length<br />

Males 850 -1000g (average 930g) 46cm >45mm >65mm<br />

Females 750-950g (average 840g) 46cm

13<br />

3.3 Distribution, habitat and home range<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> are now restricted to the South Island of New Zealand. They inhabit lowland<br />

areas of podocarp forest on the West Coast of the South Island, through to alpine<br />

beech forests, alpine meadows and mountain scree slopes along the length of the<br />

Southern Alps. A separate population inhabits the Kaikoura Mountains on the<br />

East coast of the South Island. It is not known if this is a genetically distinct<br />

population isolated from the rest of the South Island population. Genetic testing of<br />

this population is currently being undertaken by researchers at Otago University<br />

(Robertson, pers. comm., 2009).<br />

Fig 3. Present distribution of kea in the South Island of<br />

New Zealand (Robertson et al, 2007)<br />

A significant decline in kea distribution from the 1980’s has been identified in the<br />

North West part of the South Island (Robertson et al., 2007).<br />

Territories are extensive and can cover up to 4kms² (Jackson, 1969; Elliott &<br />

Kemp, 1999). Breeding pairs may have one or more nest cavities positioned on a<br />

spur and their territory will extend from the forest floor up to the alpine area above<br />

tree line (Kemp pers. comm., 2009). There has never been evidence of more than<br />

one breeding pair occupying a spur (ibid).<br />

3.4 Habits, movements and social structure<br />

Although kea are considered to be diurnal they are generally more active early<br />

morning and late afternoon/evening.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

14<br />

They are a highly gregarious species which in the wild, form large flocks with nonlinear<br />

hierarchies. Once adults reach breeding age they tend to leave the main<br />

flock and pair up for breeding (Jackson, 1963; Jackson, 1960). Studies by Clarke<br />

(1970), of kea population, movements and foods in Nelson Lakes National Park,<br />

showed very definite changes in group composition and location related to<br />

different times of the year. During August - September it was observed that kea<br />

formed flocks of 6 -8 birds which dispersed in October – December into smaller<br />

groups of 2 – 3. In January and February large flocks of up to 13 individuals again<br />

formed.<br />

Studies by Jackson (1960) in Arthur’s Pass also observed large groups of around<br />

20 first year birds during the summer period. These large flocks were then seen<br />

to disperse into groups of 2 -6 in autumn. Movement of all groups was seasonally<br />

and food related with those birds that moved to higher altitudes (1,219m –<br />

2,133m) in the warmer months observed foraging for food and retreating back to<br />

the shelter of beech forests (up to 1219m) during autumn and winter.<br />

3.5 Feeding behaviour<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> are opportunistic omnivores and consume a wide variety of foods in the wild.<br />

Behavioural, faecal and gut studies have shown that kea eat over 200+ different<br />

varieties of natural foods including a wide range of animal and vegetable matter.<br />

Foods include grasshoppers, beetles (adults and larvae), ant larvae, weta and<br />

cicada nymphs, other invertebrates and the roots, bulbs, leaves, flowers, shoots,<br />

seeds, nectar and fruit of over 200 native plant species (Brejaart, 1988; Clarke,<br />

1970).<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> have also been recorded eating other bird and mammal species including:<br />

Huttons Shearwater (chicks and eggs), racing pigeon, sheep meat and bone<br />

marrow, stoat and possum carcasses (Brejaart, 1988).<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> eating snowberries<br />

Andrew Walmsley<br />

They have also been known to consume fat<br />

from the carcasses of hunted introduced<br />

mammal species such as Tahr, deer and<br />

Chamois (Maloney, pers. comm.), and on<br />

occasion are also known to attack the fatty<br />

area around the kidneys of live sheep left<br />

high in the alpine areas (i.e. above 600m)<br />

during winter when resources are low<br />

(NHNZ, 2006).<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> are one of the few species which have<br />

managed to take advantage of humans<br />

moving in to their habitat. They use their<br />

beak, cognitive abilities and tenacity to<br />

access resources and investigate any<br />

potential uses of new objects. Rubbish<br />

dumps/bins, seasonal deer culls, farms and<br />

ski fields continue to provide useful sources<br />

of food (and toxins in some cases) for kea in<br />

times of hardship.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

15<br />

Historical burn-off of high country forests by farmers, and continued legal annual<br />

burn-off of these areas between June and October (ECAN, 2005) have<br />

significantly decreased the availability of natural food sources throughout the<br />

natural range of kea. How this impacts the survival of the species is unknown.<br />

However, research into the major cause of death in kea has historically been<br />

attributed to lack of food resources (Jackson, 1969).<br />

3.6 Reproduction<br />

Pairs are generally considered monogamous, although there have been accounts<br />

of males pairing with more than one female (Jackson, 1963). <strong>Kea</strong> reach sexual<br />

maturity around 3-4 yrs of age. Mating behaviour begins in midwinter around<br />

June. Egg laying begins in July and peaks in October, but can extend right<br />

through into January (Jackson, 1962; Jackson, 1960).<br />

Up to six eggs may be laid but the typical clutch size is 2–3 in the wild. The eggs<br />

are incubated for approx 28 days by the female. The male feeds the female at the<br />

nest entrance who in turn will regurgitate food to the chicks inside the nest. In the<br />

latter stages of rearing, the male will also directly provision the chicks until after<br />

fledging. This is a resource intensive period for the male who must not only<br />

provide for his own maintenance in often harsh conditions, but also his mate and<br />

offspring. Chicks spend up to 12 weeks or more in the nest (Pullar, 1996). <strong>Kea</strong><br />

chicks have a long juvenile period and as such are dependant on their parents for<br />

the first 4-5 months of their lives. The majority of kea chicks fledge from<br />

December – end of January (Kemp, 1999).<br />

Because of the long period associated with rearing chicks (approximately four<br />

months from start of incubation to chicks fledging) it is uncommon for kea to rear<br />

more than one brood in a season. However, if the eggs fail to hatch or are<br />

damaged, or if the chicks die or are removed, pairs will generally re-nest almost<br />

immediately. This has been observed in both the wild and captive situations<br />

(Pullar, 1996; Barrett, pers. comm. DoC, 2009).<br />

Lifestage Timeframes Time of Year<br />

Egg to hatching 28 days (23-26 days Woolcock,<br />

2000)<br />

July - October<br />

Fledgling 13 weeks December - February<br />

Parental care period Minimum 19 - 26 weeks invested in<br />

chick rearing (2-6 weeks of this after<br />

fledging)<br />

June - March<br />

Table 2: Life stages and time frames (adapted from Fijn, 2003)<br />

3.7 Protected species’ role in ecosystem<br />

<strong>Kea</strong>, as a significant berry and seed eating species in alpine areas, are<br />

considered to be important in the dispersal of the seeds of native alpine plants<br />

(Brejaart, 1988; Clarke 1970). <strong>Kea</strong> habitat covers an extensive area (4ha²) with a<br />

large proportion of this regenerating native bush from high country areas<br />

previously cleared for farming. Dispersal of native plant species in these areas is<br />

important to help combat invasion of pest plant species.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

16<br />

Although not considered carrion feeders, kea are opportunistic and have been<br />

observed feeding off the carcasses of rabbits, possums and deer which have<br />

been killed on the roads, through pest poisoning programmes and/or hunting<br />

(Walmsley, pers. comm., 2009; Maloney, pers. comm., 2009; Kemp & van Klink,<br />

2009). <strong>Kea</strong> may have played a role in cleaning up carcasses prior to human<br />

arrival.<br />

3.8 Threats in the wild<br />

The main threats to kea are intentional and unintentional human induced deaths,<br />

predation by introduced species and reduced availability of natural foods (Elliott &<br />

Kemp, in press; Kemp & van Klink, 2009; Grant, 1993; and Temple, 1996).<br />

Ongoing research continues to highlight the often widespread incidence of these<br />

pressures.<br />

3.8.1 Human Induced threats<br />

Intentional<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> underwent extensive historical persecution in a government bounty which<br />

reduced the population by an estimated 150,000 individuals (Temple, 1978;<br />

Temple 1996) from 1860 – 1971. <strong>Kea</strong> gained partial protection in 1970 and full<br />

protection in 1986 under the Wildlife Act (1952). Persecution of kea still occurs<br />

throughout the species’ range. Intentional poisoning and/or shooting of kea<br />

continues to be reported in the media (NZ Herald, 2008; McDonnell, 2009)<br />

although prosecutions are rare. Smuggling of kea for the international black<br />

market has also been documented in the past and as with other unique New<br />

Zealand species, remains a concern (Diamond & Bond, 1999).<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> were persecuted for their attacks on sheep in high<br />

country areas. Unknown artist 1882. Photo credit: Alexander<br />

Turnbull library<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

17<br />

Unintentional<br />

Human made toxins identified as having potentially widespread and extensive<br />

impacts on kea include lead (McLelland, 2009) and 1080 (Kemp & van Klink,<br />

2009). Both toxins have been used throughout kea habitat over an extended<br />

period of time and are now known to directly impact the health and survival of kea<br />

populations throughout the species’ range. Lead, predominantly in the form of<br />

lead flashing and nail heads, has been used extensively throughout the<br />

landscape since the late 1800’s – 1990’s and still exists in substantial quantities in<br />

old mining areas, public and private high country dwellings inclusive of ski fields,<br />

tramping huts and sheep stations. 1080 has also been used widely by DoC and<br />

the Animal Health Board (AHB) throughout New Zealand since the 1950’s for<br />

control of introduced pest species and in particular brushtail possums as they are<br />

a vector for bovine TB. Research is currently being conducted by the KCT and<br />

DOC into preventing 1080 poisoning with initial positive results and subsequent<br />

changes in 1080 drop protocols. Investigations into the extent of lead throughout<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> estate is currently being undertaken by the NZ Royal Society<br />

(supervised by Unitec, NZ).<br />

Other human induced causes of death include vehicle incidents, accidental<br />

capture in possum traps and ingestion of other pest control poisons, and ingestion<br />

of human foods toxic to kea (e.g. chocolate).<br />

3.8.2 Predation<br />

Predation by introduced predators such as rats, stoats and possums, has<br />

historically been considered a lesser issue to kea than many other New Zealand<br />

endemics (Elliott and Kemp, 2004). <strong>Kea</strong> ground nest and are therefore potentially<br />

as vulnerable to predation as their close relative the kaka, although nesting<br />

success has previously been found to significantly increase above 600mtrs (Elliott<br />

and Kemp, 1999). However, with evidence of predators moving higher into alpine<br />

areas, possibly due to changing climatic conditions, this threat may be increasing.<br />

Possum remains and fresh scat have being found in or around kea nest sites over<br />

1000m (KCT, unpublished report 2009). Possums may not only directly predate<br />

on nesting kea and/or their chicks, they may also compete for available nest sites<br />

and natural food sources.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

18<br />

4.0 CAPTIVE HUSBANDRY<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> are an easy species to hold badly and a difficult species to hold well.<br />

In the poorest of captive environments they will survive. However, they will not<br />

only be an unexciting exhibit for the public, but be a poor advertisement for the<br />

facility holding them. Yet in stimulating and welfare driven facilities, they make an<br />

engaging and popular exhibit that enthralls the public. <strong>Kea</strong> thrive on new<br />

experiences; they have evolved to investigate new objects in new situations and<br />

as a result are insatiably curious; a characteristic familiar to visitors to our South<br />

Island alpine huts. <strong>Kea</strong> are one of our most robust avian species, reacting more<br />

positively to stimulus than to inaction in their environment. Provision of a<br />

stimulating, complex environment should therefore be considered a basic<br />

husbandry requirement for this species.<br />

Primary reasons for holding kea in captivity are advocacy, education and<br />

research to support conservation of the species in the wild. Recommendations for<br />

management of <strong>Nestor</strong> captive populations by the <strong>Conservation</strong> Breeding<br />

Specialist Group (CBSG) state a strong research priority for this species to<br />

enhance in-situ knowledge. This includes studying and analysis of reproductive<br />

behaviours and population dynamics and developing techniques for husbandry<br />

that may be used for enhancing wild populations or help with possible reintroduction<br />

and supplementation (Grant et al., 1993).<br />

Captive facilities also play an important role in conservation through advocacy.<br />

However, the way in which animals are displayed is crucial to the perception of<br />

the public and their take home message;<br />

“In the very best zoos, wild animals can be seen as ambassadors for<br />

the survival of their species in the wild. In the worst zoos, they<br />

generate nothing but negative reactions”.<br />

– Hancock (2001)<br />

Advocacy involves taking the conservation message outside captivity to in-situ<br />

initiatives in order to increase public understanding and buy-in of conservation<br />

efforts. This is achieved through clearly displayed links to in-situ<br />

organisations/initiatives at the enclosure (for a list of links, please refer to<br />

Appendix 2).<br />

Captive holders must be aware that the public today are more cognisant of<br />

welfare standards and what constitutes natural behaviour in species. Animal<br />

welfare standards are increasingly under scrutiny, and captive holders are now<br />

obligated to provide for both the physical and behavioural necessities of species<br />

under the Animal Welfare Act, 1999 and as encouraged by the WZACS (WAZA,<br />

2005). It should be seen of particular importance that facilities run by local and<br />

central government lead the way in ensuring standards for kea are of a<br />

consistently high standard.<br />

This manual sets new standards and expectations for the husbandry of kea in<br />

New Zealand. The minimum standards in this section are designed to provide the<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

19<br />

minimum welfare guidelines for captive kea. An audit document is also included to<br />

aid facilities in assessment of their own minimum standards (Appendix 1).<br />

It is hoped that all kea holders will strive for the best practice standards outlined<br />

here and even better, exceed them.<br />

4.1 Housing/Environment Standards<br />

4.1.1 Introduction<br />

Enclosure complexity and design is crucial for maintenance of an animal’s<br />

physical and psychological wellbeing. Successful management of wild animals in<br />

captivity can be difficult, requiring housing of animals in a way that fulfils both their<br />

physical and psychological requirements (Croke, 1997; Young, 2003).<br />

From a physical point of view, if an enclosure does not enable a species to<br />

perform its basic form of locomotion, then it is viewed as deficient in design<br />

(Young, 2003). Inability of animals to perform basic locomotor behaviours (in this<br />

instance flight) may result in atrophy of associated muscle groups as well as<br />

manifestation of inappropriately directed behaviours – namely stereotypies. This<br />

is documented in Kiepers (1969) where stereotypic route pacing in wild birds was<br />

extinguished when birds were introduced to larger aviaries which allowed<br />

appropriate levels of flight. However, larger enclosures on their own are not<br />

necessarily better, as space within that area may not be physically or<br />

psychologically useable by the species concerned. Enclosure design should<br />

therefore be species specific and take into account variation in topography,<br />

substrate types (as defined by Eisenberg, 1981 as cited in Young, 2003, p 122)<br />

and include a range of useable space and levels.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> are considered a highly intelligent and complex social species with many of<br />

the attributes that support a high level of cognition (Gadjon, 2005). They are<br />

opportunistic feeders with an almost complete lack of neophobia (fear of new<br />

things), and as such fit into Kreger and Mench’s respective models of a high<br />

priority species requiring high levels of novelty and variability in their captive<br />

environment (Mench et al., 1998). Additionally, kea in the wild cover an extensive<br />

range and variety of ecotones (Diamond & Bond, 1999).<br />

The behavioural repertoire of captive kea in New Zealand facilities has been<br />

observed to be significantly effected by provision and complexity of enrichment<br />

and enclosure complexity (Orr-Walker, 2005). High enclosure standards are<br />

considered a basic requirement for this species.<br />

4.1.2 Enclosure Types<br />

There are three main types of enclosure presently housing kea in New Zealand;<br />

public walkthrough enclosures, limited access enclosures and traditional aviaries.<br />

Each has its place in housing kea and can provide vastly different experiences for<br />

kea and public alike.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

20<br />

Walkthrough enclosures are excellent for immersion and provide positive and<br />

exciting experiences for the public. Assuming that there are ample off display<br />

areas that are inaccessible to the public, and enclosures are of a size to<br />

accommodate public presence, they are also extremely effective for ongoing kea<br />

enrichment.<br />

Spot the kea! Walkthrough enclosure – Staglands<br />

Orr-Walker 2005<br />

If the design of walkthrough enclosure is carefully thought out, all life and<br />

reproductive stages can be housed successfully and safely. Additionally due to<br />

the larger size typical of these enclosures, a greater number of birds can be<br />

housed together, providing for an increased potential for complex social<br />

interactions.<br />

Pros:<br />

• Excellent advocacy and public interactive immersion experiences<br />

• Excellent enrichment opportunities for kea<br />

• Excellent social opportunities for kea<br />

• Excellent advertisement for the facility<br />

• Benefits for training and conditioning to be included in encounter<br />

Cons:<br />

• Costly<br />

• Public access may need to be monitored throughout the day to ensure<br />

public are not feeding birds, offering dangerous items or entering kea only<br />

areas<br />

• Care must be taken to meet individual kea requirements; some birds may<br />

not be suitable in public access enclosures<br />

• Potential issues relating to territorial behaviour. This would need to be<br />

assessed on an individual basis<br />

• Potential transfer/introduction of disease<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

21<br />

Limited access enclosures are useful for holding of kea where birds are less able<br />

to cope with direct human presence in their enclosure. This may be particularly<br />

true of older wild sourced birds, or non breeding pair-bonds.<br />

Limited access enclosures allow for unobstructed views of the enclosure while<br />

containing public access to one area of the enclosure by use of a solid barrier<br />

system. Birds get the benefit of the extra space the public viewing offers when the<br />

public are absent (particularly at night when kea are active).<br />

Pros:<br />

• Allows public easy viewing with<br />

no mesh between public and<br />

birds<br />

• Cost effective method of public<br />

immersion<br />

• Provides increased space for the<br />

kea<br />

• Safe for birds which may be less<br />

tolerant of public presence<br />

• Easy to construct on existing<br />

enclosures with minimal<br />

disturbance to birds<br />

• Allows for great encounters with<br />

the public (e.g. An alternative to<br />

free flight)<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> enclosure with limited public access<br />

at Paradise Valley Springs, Paradise<br />

Valley, 2009<br />

Cons:<br />

• Public access may need to be monitored as with walk through enclosures<br />

(i.e. maximum numbers in larger holdings)<br />

• Potential issues relating to territorial behaviour. This would need to be<br />

assessed on an individual basis<br />

• Potential transfer/introduction of disease<br />

Traditional aviaries are those which do not allow any human access into<br />

enclosures. They are appropriate for valuable breeding pairs which will have little<br />

desire for interaction with the public and may also be territorial during the<br />

reproductive season.<br />

Traditional aviaries do not generally enable an interactive exhibit for the public<br />

unless kea are provided with good enrichment opportunities. Excellent signage<br />

and/or interactive interpretation will increase visitor interest in these cases (i.e.<br />

encouraging observation and describing what they are seeing in the enclosure<br />

and why).<br />

Pros:<br />

• Assuming best practice standards are followed, these aviary types are<br />

good for housing valuable breeding pairs<br />

Cons:<br />

• Difficult to provide an interactive experience for the public<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

22<br />

• Advocacy potential substantially lowered<br />

• Enrichment potential for birds substantially lowered<br />

Enclosure design: Housing environment is extremely important for advocacy<br />

purposes – a poor enclosure can send the wrong message to the public and<br />

reflect badly on the facility. Enclosure design should seek to increase expression<br />

of natural behaviours in the kea of a normal duration (i.e. which decrease the<br />

incidence of stereotypic behaviours) and send a clear conservation message to<br />

the public providing a meaningful link for the public to species issues in the wild.<br />

Signage: This may be static (fixed printed signs and images), interactive (quizzes,<br />

tactile, technological, encounters) and/or passively active (e.g. video footage).<br />

Information may include:<br />

• Taxonomy<br />

• Bio-data<br />

• Natural habitat and range<br />

• Population numbers<br />

• Why are kea held in captivity?<br />

• What are the issues in the wild?<br />

• What can the public do to help the species?<br />

• Links to outside organisations for more information (KCT, DOC)*<br />

(*For a list of Links please refer to Appendix 2).<br />

Signage type:<br />

• Static: Traditional signage should be colourful, bold and to the point<br />

getting across key messages with minimal text. Use of powerful<br />

images should be used to lend weight to the text which should include<br />

questions to stimulate enquiry.<br />

• Interactive: Signage which involves some physical interaction with the<br />

public is more likely to be read and information retained (Crawford,<br />

2007). Examples may include quiz panels, tactile (kinaesthetic)<br />

displays (models of kea beaks etc), interactive touch panel video<br />

technology and/or cameras to view live animal footage<br />

• Passively active: Displays which are constantly changing rely on<br />

installation of comparatively expensive equipment, however once in<br />

place this type of display can be updated indefinitely. A video display<br />

with voice over can showcase natural kea behaviours and send key<br />

messages relating to issues in the wild thus providing a visually<br />

powerful conservation message<br />

4.1.3 Size<br />

Stating minimum enclosure sizes for captive kea is problematic. In the wild kea<br />

are strong flyers covering great distances both horizontally and vertically<br />

(altitudinal) in any one day. Satellite tracking of juveniles and observations of<br />

adult kea at Nelson Lakes (unpub. KCT, 2009) has shown birds to fly several<br />

kilometres in a matter of minutes and over 40kms in normal dispersal behaviour<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

23<br />

over a 2 month period. <strong>Kea</strong> territorial range for a breeding pair in the wild is<br />

estimated at 4km2 (Bond & Diamond, 1992).<br />

For a highly intelligent, social and mobile parrot species living in a complex alpine<br />

environment, flight, social interactions and exploration are fundamental<br />

behaviours for kea. Unfortunately captive environments for birds often allow only<br />

limited expression of these behaviours (Engebretson, 2006), denial of which can<br />

result in physical (Graham 1998) and behavioural abnormalities (van Hoek & ten<br />

Cate 1998; Garner et al., 2003b; Meehan et al., 2003a, 2004; Meehan et al.,<br />

2003b cited in Engebretson, 2006).<br />

A measure of adequate housing for kea is difficult to define as a smaller but more<br />

complex enclosure may be preferable to a large empty one. It is a combination<br />

of enclosure size, complexity and enrichment that helps prevent<br />

stereotypies and encourages the expression of natural behaviours in kea.<br />

All holders must provide sufficient space and enrichment so that birds do not<br />

develop overt stereotypic behaviours.<br />

Research on the development of locomotor stereotypies (route tracing) in parrots<br />

has been identified as related to lack of space and physical complexity while<br />

development of oral stereotypies (i.e. feather plucking) to lack of opportunity to<br />

perform foraging behaviour. Both stereotypy types are seen to be related to lack<br />

of social interaction (Sargent & Keiper 1967; Keiper 1969; Meehan et al., 2003a,<br />

2004; Meehan et al., 2003b cited in Engebretson, 2006). Changes in the captive<br />

environment including enclosure size, enrichment, and socialisation have been<br />

shown to improve the welfare of captive parrots (Engebretson, 2006).<br />

The high level of stereotypies observed in the New Zealand captive population<br />

(Orr-Walker, 2005), which include both oral and locomotor stereotypies, would<br />

suggest that the present captive environment does not provide adequately for the<br />

welfare of kea particularly in the areas of space, complexity, social structure and<br />

opportunity to perform foraging behaviours. Although the majority of facilities<br />

involved in this study have exceeded pas minimum standards, the results of this<br />

research may indicate that these still fall short for this species.<br />

An increase in enrichment, and number of feeds per day, were seen to<br />

significantly decrease the amount of stereotypic behaviours observed. The role of<br />

enclosure size and social structure was less clear although as larger enclosures<br />

tended to correspond with enclosure complexity, size may be an important factor<br />

in reducing stereotypies by providing more areas for exploration, space between<br />

animals and more opportunity with larger group size for socialisation.<br />

As such, until further research can be conducted to ascertain minimum<br />

acceptable enclosure size for kea, it should be presumed that the average<br />

enclosure size (which provides an area of

24<br />

(Each additional kea = 3m³)<br />

It is important to remember that more birds in an enclosure are likely to increase<br />

conflict issues, particularly in the case of pairings. As such simply increasing by a<br />

further 90m3/bird may not be adequate in some instances. Groupings of 6+ kea<br />

must be closely monitored to ensure that subordinate birds do not become<br />

aggressed by dominant birds or breeding pairs. Although kea can form large<br />

flocks in the wild, these tend to be fluid groupings of juveniles and sub adult birds<br />

moving over an extensive area prior to pairs forming and establishing breeding<br />

territories (Clarke, 1970).<br />

Height of the enclosure must be a minimum of 3 metres. All other proportions are<br />

up to the holder assuming that the minimum area is surpassed.<br />

The dimensions above are to be reviewed and may also be determined by group<br />

makeup (i.e. a breeding pair may be intolerant of other females in their<br />

environment whereas flocking juveniles/sub-adults may be more comfortable in<br />

larger groups).<br />

If birds are to be kept in below minimum housing areas for longer than 6 months,<br />

an exemption will need to be applied for (to be reviewed 6 monthly thereafter)<br />

Exceptions to housing standards:<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> less than three months old or undergoing medical treatment or quarantine<br />

can be held in any enclosure suitable for housing an individual of that life stage<br />

and/or medical condition temporarily (e.g. brooders, small enclosures, if required<br />

to limit movement of injured birds).<br />

Although kea should never be housed singly long-term, birds which have not<br />

been properly socialised (i.e. are hand reared and are unable to be integrated<br />

with other kea) may require a separate enclosure. This must have a minimum<br />

volume of 108m3 (6x6x3m). The number of birds unable to be integrated will<br />

decrease over time as current practice ensures birds are appropriately socialised.<br />

4.1.4 Materials for housing<br />

(For a list of housing materials and sources, refer to Appendix 3).<br />

All materials used in the construction of kea enclosures (both public display and<br />

holding facilities) should be durable, non-toxic and of a strength that can<br />

withstand manipulation by kea beaks.<br />

• Mesh – mesh size should ideally exclude entrance of pest species into the<br />

enclosure (e.g. mice, rats and sparrows). Care must be taken with<br />

galvanized welded mesh that poisoning does not occur through ingesting<br />

of coating (this should not occur in a well equipped and enriched<br />

enclosure). Mesh should extend into the ground (or conversely<br />

foundations should extend above ground level) to ensure that kea do not<br />

dig out under enclosure perimeter. Breach of containment through digging<br />

by kea has been observed.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

25<br />

Mesh must be of a strength which ensures no other animal species (e.g.<br />

dogs) can access the enclosure and that unauthorized access by humans<br />

is discouraged.<br />

Control of pest species such as rodents and sparrows may be effectively<br />

controlled with the addition of weka into the enclosure. However this<br />

requires careful monitoring and a large area with appropriate refuges for<br />

both species.<br />

• Frame – enclosure framing should be of a material that is not prone to<br />

decay over time. Care must also be taken that frame materials are not<br />

toxic. No lead based paints should be used at anytime. Tanalised timber<br />

may be used but care should be taken that there are no available perching<br />

areas which allow direct access to framing as birds may gnaw and ingest<br />

timber. Galvanised metal framing should be painted where possible or be<br />

inaccessible to birds. The keas beak is designed more for digging and<br />

probing than gnawing and they are generally less likely to gnaw on hard<br />

materials if other furniture is made available.<br />

• Footings – perimeter footings must extend well below ground level,<br />

preferably to 600mm (Pullar, 1996). Alternatively, a 600mm skirt (10mm<br />

square galvanised mesh) may be folded out from the base of the<br />

enclosure and buried approximately 50mm below ground. This skirt must<br />

run the entire enclosure perimeter. Toxic plants should be kept well clear<br />

of the enclosure perimeter fencing.<br />

• Entrance/exit doors – a double gating system where outside door must be<br />

shut before accessing the enclosure should be installed. This is essential<br />

in a public accessed enclosure. All doors must be lockable.<br />

• Nest boxes – a nest box should be provided for all enclosures which<br />

house a female whether authorised to breed or not. Nest material should<br />

also be provided during the nesting season (June – December) to all<br />

enclosures (inclusive of all male only groupings) to allow natural<br />

behaviours to be expressed. Any eggs produced by a non breeding<br />

female should be removed and replaced with dummy eggs. Nest box<br />

dimensions should ideally be 1m² with a tunnel 250mm diameter x 1m<br />

long extending from the front of the nest box (a round concrete drain is<br />

perfect for this purpose). Nest material may include tussock, hay/straw,<br />

rotten logs (kea will strip off wood and bark), sphagnum moss (available<br />

from garden centers) untreated wood wool etc. Material should be dry and<br />

free of dust, mould and foreign objects (watch for baling twine). It is<br />

particularly important that any hay/straw introduced should be<br />

checked for aspergillosis spores as this has been a cause of death in<br />

captive kea. Hay/straw must always be stored in a dry, well aired storage<br />

area to inhibit mould development.<br />

4.1.5 Shelter/screening/barriers<br />

Shelter and screening can be temporary or permanent depending on the reason<br />

for use (i.e. additional temporary screening may be required on introduction of<br />

new birds) and may be made from naturalistic or manmade materials. Rock walls<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

26<br />

or overhangs, timber structures (e.g. tramper’s huts or roofs), live vegetation or<br />

browse are examples of shelter/screening type. Public barriers in walkthrough or<br />

limited access enclosures should be obvious to visitors and of a design that<br />

discourages breaching.<br />

• Undercover area – multiple undercover areas should be made available to<br />

kea to ensure that subordinate birds are excluded by more dominant<br />

individuals. If only one area is available, it should be of a size that is able<br />

to accommodate all birds easily and must have sight barriers and multiple<br />

access/exit points. Each bird should have a 1m² area which is undercover<br />

to access. Separate naturalistic shelter areas can be achieved by<br />

provision of rock ledges, large fallen logs etc.<br />

• Visual barriers between birds – each bird should have access to at least<br />

two areas that allow visual separation from other kea. This can be in the<br />

form of vegetation, rocks or solid screens/walls.<br />

• Visual barriers to public– vegetation, rocks and barriers should be used to<br />

ensure that the public are not allowed constant visual and/or physical<br />

access to all areas of the enclosure which may cause stress to the birds.<br />

This is particularly important in the case of public access enclosures.<br />

4.1.6 Water<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> in the wild have access to fast running alpine streams and high altitude tarns<br />

at all times. Bathing in these areas is a part of daily maintenance. <strong>Kea</strong> are also<br />

sensitive to heat (Freudenberger et al., 2009) and need to be able to cool off in<br />

warmer temperatures.<br />

Fresh water must be provided at all times in enclosures. If using containers, the<br />

main water container must be large and deep enough to allow birds to bathe<br />

(approx 1m² x 200 mm deep). A second water bowl should be located elsewhere<br />

in the enclosure to ensure a subordinate bird is not kept from drinking water at<br />

any time.<br />

Ideally running water features and<br />

pools should be used in<br />

enclosures but care must be taken<br />

to ensure that birds can easily exit<br />

the pool should they fall in. Water<br />

presented in appropriate sized<br />

containers will likely be used for<br />

bathing. Positioning of the water<br />

source in relation to human<br />

proximity is therefore very<br />

important especially with respect<br />

to public access enclosures (ie<br />

water should be away from public<br />

access to ensure birds are not<br />

restricted in their use of water<br />

throughout the day).<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> bathing in enclosure stream.<br />

Photo credit: User Avenue.<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

27<br />

Running water – a water feature (natural waterfall or flowing water through/spigot<br />

system) can be easily set up with a circulating pump system. Water and<br />

receptacle area in a closed system will need changing and cleaning on a regular<br />

basis (twice weekly) to prevent build up of pathogens and algae. <strong>Kea</strong> also have a<br />

tendency to dip their food into water during feeding so it is important to ensure<br />

that food remnants are removed on a daily basis.<br />

4.1.7 Furnishings, vegetation and substrates<br />

In the wild <strong>Kea</strong> spend a large proportion of their time foraging on the ground in<br />

alpine herb fields or on the beech forest floor. They dig up the roots of plants and<br />

search for invertebrate species. It is therefore very important to provide them with<br />

diverse vegetation, substrates and enclosure furniture (such as rotting logs) that<br />

can be manipulated by the birds on a daily basis.<br />

Captive kea are predominantly held at low altitude across the length and breadth<br />

of New Zealand. These environmental conditions may not support the growth of<br />

vegetation native to their natural habitat. Local or introduced plant species will<br />

likely be more practical to grow. However care must be taken to ensure they are<br />

non toxic (refer to the list below).<br />

All new leaf-litter and soil should be screened before being placed in the<br />

enclosure to ensure it is free from harmful material such as small metal or plastic<br />

objects, and/or herbicide/pesticide residue (Fraser, 2004).<br />

Enclosures should also contain shrubs/trees. Vegetation may provide some food<br />

if appropriate species are planted. Plant cover will also generate leaf litter.<br />

In general, native plant species are considered appropriate, however if the safety<br />

of a plant species is not known then do not introduce into the enclosure until<br />

confirmed safe.<br />

The following toxic plant species must not be used in any enclosures as they<br />

are either known or thought to be toxic (see Shaw & Billing 2006 cited in Fraser,<br />

2004) This is not a complete list:<br />

• Onion Weed – Asphodelus fistulosis<br />

• Black Nightshade- Solanum nigrum<br />

• Bittersweet Nightshade – Solanum dulcamara L<br />

• Jerusalem Cherry – Solanum pseudocapsicum<br />

• Karaka – Corynocarpus laevigatus<br />

Examples of furnishings, substrates, and vegetation<br />

• Ground vegetation: kea have been observed in captivity foraging on the<br />

young shoots of grass or picking up scattered food in carex grasses. A<br />

grass area to simulate an alpine herb field in the enclosure is considered<br />

ideal to encourage expression of normal foraging behaviours.<br />

• Substrates: A variety of substrate types should be included in the<br />

enclosure to encourage foraging and digging activities. These should<br />

include, soil, leaf-litter, different sizes of stones/rocks, mulch bark and<br />

snow where possible. Different substrates can also be used to vary the<br />

topography in the enclosure and encourage natural behaviours such as<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

28<br />

climbing on moving scree slopes etc. Research into kea nest site<br />

preference indicates mainly coarse and very coarse gravel is preferred<br />

followed by gravel, and sand. Areas with silt and clay as well as areas with<br />

boulders received very low probabilities of presence (Fredenberger et al.,<br />

2009).<br />

All introduced substrate should be checked for foreign objects, spores and<br />

be screened for seeds etc. Existing soil in enclosures should be turned<br />

over each year to ensure soil health and decrease anaerobic organisms.<br />

• Trees and shrubs: <strong>Kea</strong> spend much of their time within alpine beech<br />

forests foraging for food. Enclosures should be able to support the growth<br />

of nontoxic native/exotic trees and shrubs which will provide shelter,<br />

shade, perching areas and encourage natural behaviours. Vegetation may<br />

need supplementing with browse to support investigative behaviour and<br />

decrease damage to live vegetation.<br />

• Furniture: Semi permanent items such as large logs, tree trunks, ponga<br />

logs, live trees, and multiple perches will increase the enclosures useable<br />

area and encourage flight behaviour between areas.<br />

• Human objects: Human objects can demonstrate a link for the public and if<br />

presented appropriately can provide opportunities to send useful advocacy<br />

messages to those intending to visit the South Island (e.g. don’t feed the<br />

kea, ensure your equipment stowed in kea habitat). Objects may also<br />

provide a diversity of enrichment for the kea (e.g. swandri,<br />

camping/tramping gear, ski equipment, farm equipment, DoC/tramping<br />

huts) which can readily and frequently be changed. Care must be taken<br />

to ensure that introduced items are safe, non-toxic and do not have<br />

parts which can be ingested.<br />

4.1.8 Multi-species Exhibits<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> in the wild interact with many introduced and endemic species, Native<br />

species include kaka, kakariki, bellbird, NZ robin, tomtit, blue duck and kiwi in the<br />

lowland and montane forest areas; falcon, takahe, kākāpo, rock wren and alpine<br />

reptile species in the higher alpine areas. This list is by no means exhaustive.<br />

Introduced species which share kea habitat include large grazing mammals;<br />

sheep, thar, deer and wild pigs; and smaller animals; birds, mice, rats, rabbits,<br />

stoats and possums.<br />

DOC Guidelines for holding protected wildlife for advocacy purposes (DOC,<br />

2007), states that exotic and protected native species cannot be held together. It<br />

may be argued however that in the wild kea share their environment with many<br />

introduced species and important advocacy messages and enrichment<br />

opportunities may be gained by holding kea with exotic ungulates (other exotic<br />

animal groups such as birds, rodents and mustelids would not be appropriate,<br />

unacceptably increasing the risk of disease and stress for the kea). This would be<br />

particularly interesting in a walkthrough enclosure area assuming there was<br />

ample grazing area for any large herbivores and they were of a type that was of<br />

no threat to the public. Holding appropriate exotic and endemic species together<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

29<br />

would also provide an opportunity to discuss high country farmers concerns of<br />

kea interaction with their stock and competition of grazing species for native<br />

plants on conservation land.<br />

The majority of native species listed previously would not be recommended to<br />

hold with kea unless in a very large enclosure which allowed for adequate territory<br />

sizes. <strong>Kea</strong> can become very territorial so any species held with kea must be<br />

either non-threatening to the kea, occupy quite different niches and/or be equally<br />

as robust. Each species must be given the ability to safely utilize different portions<br />

of the enclosure through provision of species specific areas (nest boxes/cavities,<br />

perches, ecotones etc). There must also be provision of adequate space and<br />

visual barriers (vegetation, topography, rocks, enclosure furniture). It is important<br />

to ensure that no corners exist where an individual animal can become trapped.<br />

Consideration of kea social structure is essential to ensure that another species<br />

are not stressed. <strong>Kea</strong> are particularly aggressive during the reproductive season<br />

and breeding pairs may not tolerate another species in their local environment.<br />

Seasonal rotation can mitigate this. Individual kea may also react quite differently<br />

to the presence of other species, therefore integration should be observed closely<br />

to ensure animals do not become stressed, injured or killed.<br />

At present only one facility in New Zealand holds kea in a multi species exhibit<br />

with weka. At the time of writing an initial integration of kea with two male weka<br />

had resulted in a weka fatality whilst subsequent integration of a pair of weka with<br />

resulting chicks was observed to be highly successful with all weka chicks<br />

successfully raised and normal behaviours of both species observed. As such<br />

introduction of kea into multi species situations must only be undertaken with<br />

standardised monitoring protocol in place and in an enclosure of significant area.<br />

Holding of kea in multi species exhibits will require further research to<br />

determine best practice and welfare standards for all species involved.<br />

Native species to be considered<br />

Weka (Gallirallus australis). Weka are a robust flightless species and have been<br />

successfully held with kea in New Zealand. Inclusion of this species in an<br />

enclosure has the added benefit of controlling pest species such as rats, mice<br />

and sparrows. Observations of the Otorohanga Kiwi House kea enclosure over a<br />

three week period showed a complete lack of pest presence (including faecal<br />

matter) and infrequent and non-injurious territorial displays by the kea to counter<br />

weka incursions into kea ‘territory’ (an undeliniated area at the front of the<br />

enclosure designated by the kea). A lack of pest species was also noted<br />

throughout the year by staff (Fortis, pers. comm., 2009) Care must be taken<br />

however as fighting between kea and weka has occurred in other holdings.<br />

Pukeko (Porphyrio porphyrio melanotus) Pukeko are a common native ground<br />

swamp dwelling species which may be used as an analogue species for the<br />

threatened Fiordland Takahe. Pukeko have a very strong beak and may be<br />

territorial so care should be taken when first introducing this species to ensure<br />

that no injuries result.<br />

Duck species <strong>Kea</strong> inhabit areas where threatened Blue Duck (Hymenolaimus<br />

malacorhynchos) are present. Other more common less territorial native duck<br />

<strong>Kea</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> Final 25/11/2010

30<br />

species such as Scaup may potentially be integrated into a multi species exhibit.<br />

Scaup and Grey duck are presently held successfully in multispecies exhibits with<br />

pukeko and weka. Their different niches should ensure they have limited and nonterritorial<br />

contact with kea. Water margin areas should be designed to be less<br />

accessible to the kea to ensure duck species are afforded safe areas to escape<br />

easily to water.<br />

The success of a multispecies exhibit depends on the ability of each species to<br />

safely utilize separate portions of the enclosure through provision of species<br />

specific areas. There must be provision of adequate space and visual barriers. No<br />

corners or funnels should exist where an individual animal may become trapped.<br />

In the case of any large grazing species, it may be prudent to have night quarters<br />

separate from the kea to ensure that a sleeping animal does not get harassed<br />

when staff are not around.<br />

Consideration of kea social structure must also be taken into account to ensure<br />

that any other species are not put under undue stress during the reproductive<br />

season. Pairs going into reproductive behaviour may not tolerate another species<br />

presence in their local environment so animals may need to be rotated seasonally<br />

in this case.<br />

4.1.9 Enclosure Siting<br />

The enclosure must be sited in such a way which provides for correct<br />

thermoregulation and humidity taking into account the following:<br />

• Sunlight: The natural environment of kea is exposed to high levels of solar<br />

radiation. Research has identified that kea prefer areas of high solar<br />

radiation (approx MJ m -2 day -1) (Freudenberger et al., 2009) although areas<br />

with very high solar radiation are preferred less than low solar radiation<br />

areas. Sunlight is very important for manufacture of vitamin D in all<br />

species (important for bone mineralization); a deficiency can result in bone<br />

softening diseases (Grant, 2005). Access to adequate sunlight (minimum<br />

2-3 hours per day) within the captive environment is considered vital for<br />

maintenance of health in kea.<br />