Publi.complète - Musée national d'histoire naturelle

Publi.complète - Musée national d'histoire naturelle

Publi.complète - Musée national d'histoire naturelle

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Ferrantia est une revue publiée à intervalles non réguliers par le <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong><br />

à Luxembourg. Elle fait suite, avec la même tomaison aux TRAVAUX SCIENTIFIQUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE<br />

NATURELLE DE LUXEMBOURG.<br />

Comité de rédaction:<br />

Eric Buttini<br />

Guy Colling<br />

Edmée Engel<br />

Thierry Helminger<br />

Marc Meyer<br />

Mise en page:<br />

Romain Bei<br />

Design:<br />

Service graphique du MNHN<br />

Prix du volume: 10 €<br />

Rédaction:<br />

<strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong><br />

Rédaction Ferrantia<br />

25, rue Münster<br />

L-2160 Luxembourg<br />

tel +352 46 22 33 - 1<br />

fax +352 46 38 48<br />

Internet: http://www.naturmusee.lu<br />

email: ferrantia@mnhn.lu<br />

Echange:<br />

Exchange MNHN-SNL<br />

c/o <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong><br />

25, rue Münster<br />

L-2160 Luxembourg<br />

tel +352 46 22 33 - 1<br />

fax +352 46 38 48<br />

Internet: http://www.mnhnl.lu/biblio/exchange<br />

email: exchange@mnhnl.lu<br />

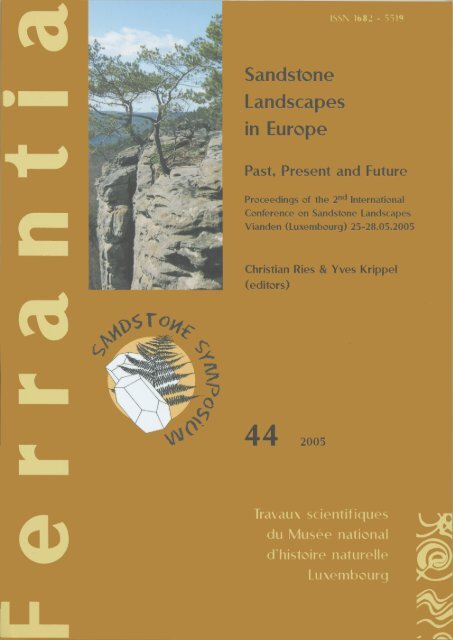

Page de couverture:<br />

Logo du symposium. Réalisation: Anita Faber, Service graphique du MNHN.<br />

Grès de Luxembourg avec Pinus sylvestris près de Berdorf. Photo: Yves Krippel.<br />

Citation:<br />

Ries C. & Krippel Y. (Editors) 2005. - Sandstone Landscapes in Europe - Past, Present and Future.<br />

Proceedings of the 2 nd Inter<strong>national</strong> Conference on Sandstone Landscapes. Vianden (Luxembourg)<br />

25-28.05.2005. Ferrantia 44, 256 p. MNHN, Luxembourg.<br />

Date de publication:<br />

31 décembre 2005<br />

(réception du manuscrit: 15 août 2005)<br />

Impression:<br />

Imprimerie Graphic Press Sàrl, Mamer, Luxembourg<br />

© <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong> Luxembourg, 2005 ISSN 1682-5519

Ferrantia<br />

44<br />

Sandstone Landscapes in Europe<br />

Past, Present and Future<br />

Proceedings of the 2 nd Inter<strong>national</strong> Conference<br />

on Sandstone Landscapes<br />

Vianden (Luxembourg) 25-28.05.2005<br />

Christian Ries & Yves Krippel (Editors)<br />

Luxembourg, 2005<br />

Travaux scientifiques du <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong> Luxembourg

Table of contents - Table des matières<br />

Preface of the editors 7<br />

Conference poster 12<br />

Conference programme 13<br />

Conference opening<br />

Frantzen-Heger, Gaby. - Allocution de bienvenue de la bourgmestre<br />

(Welcome speech of the mayor) 15<br />

Werner, Jean. - Allocution de bienvenue de la part des organisateurs<br />

(Organizers welcome speech) 17<br />

Oral communications - Communications orales<br />

1. Evolution of sandstone landscapes: geology and geomorphology<br />

Evolution des paysages de grès: géologie et géomorphologie<br />

Adamovič, Jiří. - Sandstone cementation and its geomorphic and hydraulic implications. 21<br />

Juilleret, Jérôme, Jean-Francois Iffly, Patrick Matgen, Cyrille Taillez, Lucien Hoffmann &<br />

Laurent Pfister. - Soutien des débits d’étiage des cours d’eau du Grand-Duché du<br />

Luxembourg par l’aquifère du Grès du Luxembourg. 25<br />

Jung, Jürgen. - Sandstone-Saprolite and its relation to geomorphological processes -<br />

examples from Spessart/Germany as a sandstone-dominated highland-region. 31<br />

Mikuláš, Radek. - Features of the sandstone palaeorelief preserved: The Osek area,<br />

Miocene, Czech Republic. 37<br />

Robinson, D.A. & R.B.G. Williams. - Comparative morphology and weathering characteristics<br />

of sandstone outcrops in England, UK. 41<br />

Thiry, Médard. - Weathering morphologies of the Fontainebleau Sandstones and related silica<br />

mobility. 47<br />

Vařilová, Zuzana & Jiří Zvelebil. - Sandstone Relief Geohazards and their Mitigation:<br />

Rock Fall Risk Management in Bohemian Switzerland National Park. 53<br />

2. Archaeology of sandstone landscapes: from Prehistory to the Middle Ages<br />

Archéologie des paysages de grès: de la Préhistoire au Moyen-Âge<br />

Auffret, Marie-Claude & Jean-Pierre Auffret. - Similitudes et différences dans l’art rupestre<br />

post glaciaire de Cantabrie (Espagne), Bassin parisien sud (France), Picardie, Oise et<br />

Aisne (Tardenois, France), Vosges du nord (Bas Rhin et Moselle, France) et Luxembourg. 59<br />

Bénard, Alain. - Aperçu de l’art rupestre des chaos gréseux stampien du Massif de<br />

Fontainebleau, France. 65<br />

Dimitriadis, George. - A Prehistoric Sandstone Landscape: Camonica Valley, Italy. 69<br />

Hauzeur, Anne & Foni Le Brun-Ricalens. - Grès et préhistoire au Luxembourg: Rupture et<br />

continuité dans les stratégies d’implantation et d’approvisionnement liées aux<br />

formations gréseuses durant le Néolithique. 71<br />

Le Brun-Ricalens, Foni & François Valotteau. - Patrimoine archéologique et Grès de<br />

Luxembourg: un potentiel exceptionnel méconnu. 77<br />

Schwenninger, Jean-Luc. - Optical dating of sand grains: Recent advances and applications<br />

in archaeology and Quaternary research. 83

4<br />

3. Flora, fauna and microclimate of sandstone ecosystems<br />

Flore, faune et microclimat des écosystèmes gréseux<br />

Colling, Guy & Sylvie Hermant. - Genetic variation in an isolated population of<br />

Hymenophyllum tunbrigense. 89<br />

Harbusch, Christine. - Bats and sandstone: the importance of sandstone regions in<br />

Luxembourg for the ecology and conservation of bats. 93<br />

Hoffmann, Lucien & Tatyana Darienko. - Algal biodiversity on sandstone in Luxembourg. 99<br />

Härtel, Handrij & Ivana Marková. - Phytogeographic importance of sandstone landscapes. 103<br />

Pokorný, Petr & Petr Kuneš. - Holocene acidification process recorded in three pollen profiles<br />

from Czech sandstone and river terrace environments. 107<br />

Monnier, Olivier, Martial Ferréol, Frédéric Rimet, Alain Dohet, Christophe Bouillon,<br />

Henry-Michel Cauchie, Lucien Hoffmann & Luc Ector. - Le Grès du Luxembourg:<br />

un îlot de biodiversité pour les diatomées des ruisseaux. 115<br />

Muller, Serge. - Les phytocénoses d’indigénat du Pin sylvestre (Pinus sylvestris L.) sur les<br />

affleurements de grès du Pays de Bitche (Vosges du Nord). 119<br />

Signoret, Jonathan. - Les pineraies à caractère naturel au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg:<br />

caractéristiques, conservation et suivi. 123<br />

Świerkosz, Krzysztof & Marek Krukowski. - Main features of the sandstone flora and plant<br />

communities of the North-Western part of Sudetes Foreland. 127<br />

Werner, Jean. - Intérêt et richesse de la flore bryologique du Grès hettangien (Luxembourg,<br />

Eifel et Lorraine). 133<br />

4. Human impact on sandstone landscapes: threats and protection<br />

Impacts humains sur les paysages de grès: menaces et conservation<br />

Alexandrowicz, Zofia & Jan Urban. - Sandstone regions of Poland – Geomorphological types,<br />

scientific importance and problems of protection. 137<br />

Duchamp, Loïc. - Une charte pour la pratique de l’escalade sur les rochers du Parc naturel<br />

régional des Vosges du Nord. 143<br />

Krippel, Yves. - Is the conservation of the natural and cultural heritage of sandstone<br />

landscapes guaranteed? Case study of the Petite Suisse area in Luxembourg. 147<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

Posters<br />

1. Evolution of sandstone landscapes: geology and geomorphology<br />

Evolution des paysages de grès: géologie et géomorphologie<br />

Colbach, Robert. - Overview of the Geology of the Luxembourg Sandstone(s). 155<br />

Faber, Alain & Robert Weis. - Le Grès de Luxembourg: intérêt scientifique et patrimonial<br />

de ses sites fossilifères. 161<br />

Jung, Jürgen. - Cretaceous-Tertiary weathering in sandstones of the Southwest Spessart/<br />

Germany. 165<br />

Mertlík, Jan & Jiří Adamovič. - Some significant geomorphic features of the Klokočí Cuesta,<br />

Czech Republic. 171<br />

Schweigstillová, Jana, Veronika Šímová & David Hradil. - New investigations of the salt<br />

weathering of Cretaceous sandstones in Northern Bohemia, Czech Republic. 177<br />

Urban, Jan. - Pseudokarst caves as an evidence of sandstone forms evolution – a case study<br />

of Niekłań, the Świętokrzyskie Mts., central Poland. 181<br />

2. Archaeology of sandstone landscapes: from Prehistory to the Middle Ages<br />

Archéologie des paysages de grès: de la Préhistoire au Moyen-Âge<br />

Le Brun-Ricalens, Foni. - Grès de Luxembourg et Art rupestre: L’œuvre du Dr E. Schneider<br />

et la correspondance inédite (1937-1949) avec l’abbé H. Breuil. 187<br />

Le Brun-Ricalens, Foni, Jean-Noël Anslijn, Frank Broniewski & Susanne Rick. - Le projet FNR<br />

«Espace et Patrimoine Culturel»: un outil de gestion informatisé au service du<br />

Patrimoine luxembourgeois. L’exemple de la zone-pilote du Müllerthal. 193<br />

Valotteau, François & Foni Le Brun-Ricalens. - Grès de Luxembourg et Mégalithisme : bilan<br />

après 5 années de recherche. 199<br />

3. Flora, fauna and microclimate of sandstone ecosystems<br />

Flore, faune et microclimat des écosystèmes gréseux<br />

Colling Guy, Thierry Helminger & Jim Meisch. - Microclimatic conditions in a sandstone<br />

gorge with Hymenophyllum tunbrigense. 205<br />

Krippel, Yves. - The Hymenophyllaceae (Pteridophyta) in Luxembourg. Past, present and future. 209<br />

Liron, Marie Nieves & Médard Thiry. - Peaty micro-zones on the sandstone ridges of the<br />

Fontainebleau Massif (France): hydrology and vegetation biodiversity. 215<br />

Marková, Ivana. - Bryophyte diversity of Bohemian Switzerland in relation to microclimatic<br />

conditions. 221<br />

Stomp, Norbert & Wanda M. Weiner. - Some remarkable species of Collembola (Insecta,<br />

Apterygota) of the Luxembourg sandstone area. 227<br />

Turoñová, Dana. - Mapping and monitoring of Killarney Fern (Trichomanes speciosum) in the<br />

Czech Republic. 233<br />

Urbanová, Hana & Jan Procházka. - Kokořínsko Protected Landscape area – Rare species,<br />

protection and conservation. 237<br />

Photos of the conference - Photos de la conférence 239<br />

On behalf of the participants - Au nom des participants 245<br />

List of participants - Liste des participants 247<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

5

6<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

C. Ries & Y. Krippel Preface of the Editors<br />

Preface of the Editors<br />

Introduction<br />

You hold in hands the proceedings of the second<br />

inter<strong>national</strong> conference on sandstone landscapes<br />

that took place in Vianden (Luxembourg) from<br />

May 25 to May 28 2005. The conference entitled<br />

“Sandstone landscapes in Europe - Past, present and<br />

future” brought together a range of scientists,<br />

experts, teachers and students from all over<br />

Europe.<br />

This inter<strong>national</strong> sandstone symposium followed<br />

the initial conference “Sandstone Landscapes:<br />

Diversity, Ecology and Conservation” that took place<br />

in Doubice in Saxonian-Bohemian Switzerland,<br />

Czech Republic in September 2002 (Härtel et al.<br />

2002).<br />

The proposal for the follow-up symposium was brought<br />

to Luxembourg by a Luxembourg participant who<br />

attended the Czech symposium.<br />

The “Groupe d’études ayant pour objet la conservation<br />

du patrimoine naturel de la Petite-Suisse luxembourgeoise”,<br />

an advisory group created by the Luxembourg<br />

Government to promote the conservation<br />

of remarkable natural sites in the Luxembourg<br />

sandstone area, the Müllerthal, also known as<br />

the “Petite-Suisse luxembourgeoise”, supported<br />

the initiative to organize the next sandstone<br />

symposium in Luxembourg.<br />

So the idea made its way, a partnership was set up<br />

and the symposium was scheduled for May 2005.<br />

Organization<br />

Organizations and persons are listed in alphabetical<br />

order.<br />

Main organizers<br />

• Administration des eaux et forêts (Water and<br />

forestry administration)<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Christian RIES<br />

Department of Ecology, National Museum of Natural History<br />

25, rue Münster, L-2160 Luxembourg<br />

cries@mnhn.lu<br />

Yves KRIPPEL<br />

Research associate of the Luxembourg National Museum of Natural History<br />

18A, rue de Rollingen, L-7475 Schoos<br />

yves.krippel@mnhn.lu<br />

• <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong> (National<br />

Museum of Natural History)<br />

• <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire et d’art (National<br />

Museum of History and Art)<br />

• Société des naturalistes luxembourgeois<br />

(Luxembourg Naturalist Society)<br />

Partner organizations<br />

• Amis de la géologie, de la minéralogie et de<br />

la paléontologie du Luxembourg (Friends of<br />

geology, mineralogy and palaeontology in<br />

Luxembourg)<br />

• Association des géologues luxembourgeois<br />

(Luxembourg geologists association)<br />

• Fondation Hëllef fir d’Natur (Help for nature<br />

foundation)<br />

• LAG LEADER+ Mullerthal (Local action group<br />

Leader +)<br />

• NATURA - Ligue luxembourgeoise pour la<br />

protection de la nature et de l'environnement<br />

(Luxembourg league for the environment and<br />

nature conservation)<br />

• Naturerkundungsstation Teufelsschlucht<br />

(Nature visitor center)<br />

• Oeko-Zenter Lëtzebuerg (Environmental and<br />

nature conservation foundation)<br />

• Service géologique du Luxembourg (Geological<br />

survey of Luxembourg)<br />

• Société préhistorique luxembourgeoise<br />

(Luxembourg prehistorical society)<br />

Conference coordination and secretariate<br />

• Christian Ries, curator at the National Museum<br />

of Natural History, president of the Luxembourg<br />

Naturalist Society<br />

7

C. Ries & Y. Krippel Preface of the Editors<br />

8<br />

Conference scientific committee<br />

• Guy Colling, researcher at the National<br />

Museum of Natural History<br />

• Alain Faber, curator at the National Museum of<br />

Natural History<br />

• Yves Krippel, research associate of the National<br />

Museum of Natural History<br />

• Christian Ries, curator at the National Museum<br />

of Natural History, president of the Luxembourg<br />

Naturalist Society<br />

• Jean-Marie Sinner, head of Diekirch forestry<br />

district, Water and Forests Administration<br />

• Fernand Spier, president of the Luxembourg<br />

Prehistory Society<br />

• Norbert Stomp, honorary director of the<br />

National Museum of Natural History<br />

• François Valotteau, researcher at the National<br />

Museum of History and Art<br />

• Jean Werner, president of the Study group<br />

for the preservation of the natural heritage of<br />

Luxembourg Little Switzerland<br />

Conference organizing committee<br />

• Georges Bechet, director of the National<br />

Museum of Natural History<br />

• Marie-Paule Kremer, Ministry of Environment<br />

• Frantz-Charles Muller, president of Foundation<br />

'Hëllef fir d’Natur' and NATURA<br />

• Christian Ries, curator at the National Museum<br />

of Natural History, president of the Luxembourg<br />

Naturalist Society<br />

• Jean-Marie Sinner, head of Diekirch forestry<br />

district, Water and Forests Administration<br />

• François Valotteau, researcher at the National<br />

Museum of History and Art<br />

Background and aims<br />

of the conference<br />

Sandstone regions are scattered all over Europe.<br />

Even if different in age and composition, they<br />

all show a great number of similitudes. Distinct<br />

geomorphologic features often create strong<br />

gradients in mesoclimatic conditions and generate<br />

high levels of natural disturbance and resulting<br />

patch dynamics. In sandstone regions these<br />

dynamic geomorphologic processes occur at rates<br />

unseen in the surroundings. The special climatic<br />

or microclimatic conditions in sandstone regions<br />

induce a mosaic of biotopes hosting specific flora<br />

and fauna. The occurring species are often of relict<br />

nature and a testimony of climatic conditions and<br />

vegetation in place earlier in this interglacial.<br />

Sandstone areas are not only a phenomenon of<br />

geological and biological interest. They are well<br />

known for their prehistoric past, and rock shelters<br />

provided excellent opportunities for human<br />

settlements. Later, the outstanding landscapes of<br />

sandstone regions have attracted human attention,<br />

particularly since the Romantic period. It was<br />

the beginning of tourism, a phenomenon that<br />

nowadays often causes irreversible problems in<br />

these fragile environments.<br />

In order to preserve the invaluable landscapes and<br />

ecosystems, associated to sandstone landscapes,<br />

there is a strong need for research, nature and<br />

landscape conservation with concrete management<br />

plans, environmental friendly tourism, etc.<br />

The first sandstone conference in Doubice, Czech<br />

Republic, revealed that the uniqueness of geomorphologic<br />

and ecological processes in sandstone<br />

regions calls for a much more intimate link<br />

between geomorphology, climatology, landscape<br />

history and biology/ecology, etc. and initiated<br />

the so-called 'sandstone community', a database<br />

of people interested in research and conservation<br />

of sandstone landscapes. More information can<br />

be found on the 'Sandstone Landscapes' website<br />

www.sandstones.org, providing information<br />

about the research and events on sandstone<br />

landscapes, especially in Europe (Härtel 2005).<br />

This second inter<strong>national</strong> conference on sandstone<br />

tried to carry on the effort devoted to bridging<br />

all the concerned disciplines. The organizers<br />

intended that this conference would - amongst<br />

others - identify which general research topics<br />

can use sandstone regions as particularly suitable<br />

model systems; permit the comparison of different<br />

sandstone regions in Europe and point out similarities;<br />

establish new contacts and further collaboration<br />

among people interested in sandstone<br />

regions; address conservation issues specific for<br />

sandstone regions (tourism, rock climbing, restoration<br />

management); etc.<br />

Scientific programme<br />

The scientific programme consisted of plenary<br />

lectures, poster sessions, discussions and excursions.<br />

Four major topics were covered by 26 oral<br />

communications and 16 posters:<br />

1. Evolution of sandstone landscapes:<br />

geology and geomorphology<br />

Sandstone is a quite common rock type, which<br />

characterizes different regions and yet each<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

C. Ries & Y. Krippel Preface of the Editors<br />

sandstone formation differs somehow from the<br />

other by its mineralogical composition or by its<br />

origin. Today the geological evolution of these<br />

areas shows a landscape revealing many erosion<br />

features, joint patterns and rockslides from<br />

recent time, as well as a lot of elements from the<br />

geological past. The erosion often formed either<br />

narrow valleys into a sandstone plateau, or slopes<br />

of a cuesta, or buttes as residual hills or outliers,<br />

etc.<br />

2. Archaeology of sandstone landscapes:<br />

from Prehistory to the Middle Ages<br />

There is no doubt about the importance of<br />

sandstone landscapes from Prehistory to the<br />

Middle Ages. Archaeology contributes to the<br />

knowledge of the old populations within the<br />

limits given by the subject. Following topics are<br />

of special interest: the habitat and its additional<br />

activities, as well as architecture; burials, anthropology<br />

and taphonomy in sandy context; petroglyphs<br />

and rupestral art.<br />

3. Flora, fauna and microclimate of<br />

sandstone ecosystems<br />

Sandstone formations with their typical erosion<br />

features are known for special microclimatic<br />

conditions. Great variations in both humidity and<br />

temperature - including temperature inversion -<br />

are responsible for a huge diversity of plants and<br />

animals. The proliferation of Atlantic and sub-<br />

Atlantic species is remarkable; the presence of<br />

mountain and sub-mountain species is significant.<br />

Besides higher plants, the diversity of pteridophytes<br />

and the richness of nonvascular cryptogams<br />

like bryophytes and lichens of sandstone regions<br />

is in general outstanding. On the other hand, the<br />

sandstone outcrops, as well as extended woods<br />

and moist valleys offer habitats for a rich wildlife.<br />

4. Human impact on sandstone<br />

landscapes: threats and protection<br />

Sandstone landscapes often became the victims<br />

of their own success. Exploited and inhabited<br />

by man since prehistory, visited and solicited by<br />

modern man, seeking relaxation and ventures in<br />

these spectacular landscapes, the extreme fragile<br />

sandstone habitats are more and more threatened.<br />

In order to preserve the natural and cultural<br />

heritage of sandstone landscapes, concrete<br />

measures must be initiated and a tourism in accordance<br />

with the environment promoted.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Course of the Symposium<br />

88 participants attended the conference, including<br />

speakers and translation staff (cf. list of participants).<br />

Pre-conference excursion<br />

The pre-conference excursion on Wednesday<br />

May 25 took the participants by bus to the heart<br />

of the “Petite Suisse” area. The participants were<br />

split into two groups according to the conference<br />

languages English and French.<br />

On the programme: sandstone formations, forests<br />

and valleys around Berdorf and Beaufort (Fig. 1).<br />

The prehistoric sites of 'Kalekapp', petroglyphs<br />

and vandalism, rock formations and erosion,<br />

different forest associations, flora (including filmy<br />

ferns), fauna, rock climbing and related problems,<br />

tourism as well as nature conservation, were only<br />

some of the topics.<br />

The field trip was rather demanding, but the<br />

barbecue during lunch break in the stunning<br />

scenery of Beaufort castle helped to forget aching<br />

legs and sunburn.<br />

The guides were: Guy Colling, Alain Faber, Anne<br />

Hauzeur, Yves Krippel, Jean-Marie Sinner and<br />

François Valotteau.<br />

The conference<br />

The plenary sessions lasted the next two days, from<br />

Thursday May 26 to Friday May 27. The venue<br />

was the 'Centre culturel Larei', a former tannery<br />

complex transformed by the city of Vianden into a<br />

cultural centre. An abstract book was provided by<br />

the organizers (Ries 2005).<br />

Instead of grouping the communications by major<br />

themes into distinct Symposia, the organizing<br />

committee was so audacious to mix up the<br />

contributions independently of their topic (cf.<br />

Fig. 1: Pre-conference excursion in the Müllerthal area,<br />

May 25 2005. Photo: Milkuláš Radek.<br />

9

C. Ries & Y. Krippel Preface of the Editors<br />

10<br />

programme). Under the bottom line, as everybody<br />

agreed, this atypical method was of great success.<br />

It is quite unusual that the last speaker of the day<br />

can find himself in front of a full auditory, most<br />

people having attended all day long. Of course<br />

this fact is also due to the excellent quality of the<br />

contributions and to the fact that the programme<br />

was reliable, all speakers perfectly respecting their<br />

allocated time.<br />

We are especially thankful to Handrij Härtel and<br />

Jan Čeřovský who draw general conclusions at<br />

the conference closure and called for joining the<br />

sandstone community and for meeting again at the<br />

next conference which will be held in Poland in a<br />

couple of years. Jan Čeřovský draw the attention<br />

to the range of activities and working groups<br />

of the IUCN and proposed that the sandstone<br />

community should create an IUCN-working<br />

group covering the issues of sandstone areas.<br />

On Friday May 27, after the second morning<br />

session, the organizers were happy to present<br />

the book about the Petite-Suisse area and to offer<br />

a copy to each participant (Fig. 2). The book<br />

comprises 251 pages and covers all the topics of<br />

the conference (Krippel 2005).<br />

After the conference closure, the tourist train<br />

'Benni' took the participants to a guided visit of the<br />

hydro electrical power plant SEO near Stolzembourg.<br />

The conference dinner took place the same<br />

evening in the Hotel Victor Hugo in Vianden.<br />

Post-conference excursion<br />

The post-conference excursion took the participants<br />

by bus to the German part of the Luxembourg<br />

sandstone area near Ernzen and Ferschweiler.<br />

Again the participants were split into two<br />

groups according to the conference languages<br />

English and French.<br />

Fig. 2: Presentation of the book about the Petite-Suisse<br />

area in front of the conference venue Larei, May 27<br />

2005. Photo: Milkuláš Radek.<br />

Fig. 3: Post-conference excursion, Luxembourg-city,<br />

view on the Alzette valley and the Grund district, May<br />

28 2005. Photo: Jiří Adamovič.<br />

After a glance at the visitor centre 'Naturerkundungszentrum<br />

Teufelsschlucht', a trail took the<br />

participants through sandstone formations and<br />

deciduous woods to the valley of the Prüm and<br />

the 'Irreler Wasserfälle', small waterfalls caused by<br />

enormous rock boulders.<br />

The afternoon was spent in Luxembourg-city<br />

covering geological, historical and botanical topics<br />

(Fig. 3). The excursion ended with a visit of two<br />

major museums, the National Museum of Natural<br />

History and the National Museum of History and<br />

Art.<br />

The guides were: Georges Bechet, Alain Faber,<br />

Anne Hauzeur, François Valotteau and Holger<br />

Weber.<br />

Conclusion<br />

On behalf of the organizers we thank all the<br />

participants having attended the conference and<br />

especially those who have contributed to the<br />

programme excellence with a high diversity and<br />

quality of oral communications and poster presentations.<br />

The magnificent weather conditions, the gorgeous<br />

conference venue and last but not least the sociability<br />

and sincerity of the participants made this<br />

symposium a remarkable event that will not be<br />

forgotten soon.<br />

The conference showed clearly the similitude of<br />

the different sandstone landscapes scattered all<br />

over Europe and the similarities of the problematic<br />

of conservation of natural and cultural heritages<br />

in the different regions. By gathering participants<br />

of other countries, the Sandstone Community was<br />

enlarged and there was a clear consensus to join<br />

efforts in the future.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

C. Ries & Y. Krippel Preface of the Editors<br />

We hope these proceedings will contribute to<br />

spread knowledge about one of the most sensible<br />

landscape types in Europe and will increase<br />

networking amongst the scientific community<br />

working in and on sandstone areas.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We are grateful to a range of persons and institutions<br />

which have helped in many ways and thus<br />

contributed to the success of the conference. These<br />

persons and institutions are listed by type and<br />

in alphabetical order. We express these thanks<br />

on behalf of the main organizers, the partner<br />

organizations and the scientific and organizing<br />

committees.<br />

Excursion guides<br />

• Georges Bechet (National Museum of Natural<br />

History, Luxembourg)<br />

• Guy Colling (National Museum of Natural<br />

History, Luxembourg)<br />

• Alain Faber (National Museum of Natural<br />

History, Luxembourg)<br />

• Anne Hauzeur (research associate, National<br />

Museum of History and Art, Luxembourg)<br />

• Yves Krippel (research associate, National<br />

Museum of Natural History, Luxembourg)<br />

• Jean-Marie Sinner (Forestry administration,<br />

Diekirch)<br />

• François Valotteau (National Museum of<br />

History and Art, Luxembourg)<br />

• Holger Weber (Naturerkundungszentrum<br />

Teufelsschlucht, Germany)<br />

Staff<br />

• Bastin Jonny (Municipality<br />

conference venue Larei)<br />

of Vianden,<br />

• Pascal Dellea (driver)<br />

• Nadine De Sousa (student, Hotel school<br />

Diekirch)<br />

• Véronique Maurer (student, Hotel school<br />

Diekirch)<br />

• Tom Müller (Forestry administration, Beaufort)<br />

and his team (barbecue in Beaufort Castle)<br />

Graphical work<br />

• Anita Faber (National Museum of Natural<br />

History, Luxembourg)<br />

• Thierry Helminger (National Museum of<br />

Natural History, Luxembourg)<br />

Sponsors<br />

• Fonds <strong>national</strong> de la recherche, Luxembourg<br />

(National Research Fund)<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

• Luxembourg Presidency of the Council of the<br />

European Union<br />

• Ministry of Culture, Higher Education and<br />

Research, Luxembourg<br />

• Ministry of Environment, Luxembourg<br />

• Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Luxembourg<br />

• Mrs. Anne-Marie Linkels (Castle of Beaufort)<br />

• Municipality of Beaufort<br />

• Municipality of Vianden<br />

• SEO, Société électrique de l’Our, Vianden<br />

• Tourist office of Vianden<br />

Companies<br />

• Accents sprl, Brussels (Simultaneous translation)<br />

• Alltec solution providers, Luxembourg<br />

(Materials)<br />

• Autolux sàrl, Luxembourg (Car rental)<br />

• Dorel Doreanu, Senningen (Music)<br />

• Economat Stronska Fons, Vianden (Catering)<br />

• E.G.E. Stienon sprl, Brussels (Sound and simultaneous<br />

translation technique)<br />

• Hammes sàrl, Vianden (Tourist train Benni)<br />

• Hotel Victor Hugo, Vianden (Catering)<br />

• Hotel Petry, Vianden (Catering)<br />

• Maison Bernard Bergh, Vianden (Materials)<br />

• Shop Vinandy, Vianden (Fuel)<br />

• Voyages Demy Schandeler, Keispelt (Bus transportation)<br />

References<br />

Härtel H. 2005. - Sandstone Landscapes. Website<br />

of the Sandstone Community. Url: http://www.<br />

sandstones.org/s_conf.htm [15.11.2005].<br />

Härtel H., Herben T. & Cílek V. 2002. - Sandstone<br />

Landscapes: Diversity, Ecology and Conservation.<br />

Conference homepage. Url: http://<br />

www.sandstones.org/ibot_sandstone/index.<br />

htm [15.11.2005].<br />

Krippel Y. [ed.] 2005. - Die Kleine Luxemburger<br />

Schweiz - Geheimnisvolle Felsenlandschaft im<br />

Wandel der Zeit. Luxembourg. 251p. ISBN 2-<br />

919877-09-7.<br />

Ries C. 2005. - Sandstone landcapes in Europe<br />

- Past, present and future. 2nd Inter<strong>national</strong><br />

Conference on sandstone landcapes. Conference<br />

abstracts - Préactes de la conférence.<br />

Url: http://www.symposium.lu/symposium/<br />

sandstone/preactes.pdf [15.11.2005]<br />

11

Conference poster Poster de la conférence<br />

12<br />

Poster layout: Thierry Helminger (MNHNL). Logo design: Anita Faber (MNHNL)<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

Conference programme Programme de la conférence<br />

Conference programme<br />

Programme de la conférence<br />

Note of the editors: the authors who presented the<br />

oral communication at the conference are marked<br />

with the sign * after their last name.<br />

Wednesday May 25 2005<br />

Pre-conference excursion (Müllerthal, L)<br />

Thursday May 26 2005<br />

Conference opening<br />

Welcome speeches by Mrs. Gaby Frantzen-Heger,<br />

Mayor of Vianden, and Mr. Jean Werner on behalf<br />

of the organizers.<br />

Session I<br />

Chairman: Yves Krippel (L)<br />

Handrij Härtel* & Ivana Marková. - Phytogeographic<br />

importance of sandstone landscapes (CZ)<br />

Jiří Adamovič*. - Sandstone cementation and its<br />

geomorphic and hydraulic implications (CZ)<br />

Krzysztof Świerkosz & Marek Krukowski*. -<br />

Main features of the sandstone flora and plant<br />

communities of the North-Western part of Sudetes<br />

Foreland (PL)<br />

Session II<br />

Chairman: Handrij Härtel (CZ)<br />

Zuzana Vařilová & Jiří Zvelebil*. - Sandstone Relief<br />

Geohazards and their Mitigation: Rock Fall Risk<br />

Management in Bohemian Switzerland National<br />

Park (CZ)<br />

Médard Thiry*. - Weathering morphologies of<br />

the Fontainebleau Sandstones and related silica<br />

mobility (F)<br />

Alain Bénard*. - Aperçu de l’art rupestre des chaos<br />

gréseux stampien du Massif de Fontainebleau,<br />

France (F)<br />

Petr Pokorný* & Petr Kuneš. - Holocene acidification<br />

process recorded in three pollen profiles<br />

from Czech sandstone and river terrace environments<br />

(CZ)<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Session III<br />

Chairman: Jean-Luc Schwenninger (UK)<br />

David A. Robinson* & Rendel B. G. Williams. -<br />

Comparative morphology and weathering characteristics<br />

of sandstone outcrops in England, UK<br />

(UK)<br />

Radek Mikuláš*. - Features of the sandstone<br />

palaeorelief preserved: The Osek area, Miocene,<br />

Czech Republic (CZ)<br />

Guy Colling* & Sylvie Hermant. - Genetic variation<br />

in an isolated population of Hymenophyllum tunbrigense<br />

(L)<br />

Loïc Duchamp*. - Une charte pour la pratique de<br />

l’escalade sur les rochers du Parc naturel régional<br />

des Vosges du Nord (F)<br />

Poster session<br />

Session IV<br />

Chairwoman: Anne Hauzeur (B)<br />

Foni Le Brun-Ricalens & François Valotteau*. -<br />

Patrimoine archéologique et Grès de Luxembourg:<br />

un potentiel exceptionnel méconnu (L)<br />

Handrij Härtel*. - Sandstone landscapes: research,<br />

conservation and future co-operation within the<br />

Sandstone Community (CZ)<br />

Informal discussion on sandstone community<br />

during and after dinner<br />

Friday May 27 2005<br />

Session V<br />

Chairman: Guy Colling (L)<br />

Jérôme Juilleret*, Jean-Francois Iffly, Patrick<br />

Matgen, Cyrille Taillez, Lucien Hoffmann &<br />

Laurent Pfister. - Soutien des débits d’étiage des<br />

cours d’eau du Grand-Duché du Luxembourg par<br />

l’aquifère du Grès du Luxembourg (L)<br />

Lucien Hoffmann* & Tatyana Darienko. - Algal<br />

biodiversity on sandstone in Luxembourg (L &<br />

UA)<br />

Christine Harbusch*. - Bats and sandstone: the<br />

importance of sandstone regions in Luxembourg<br />

for the ecology and conservation of bats (D)<br />

13

Conference programme Programme de la conférence<br />

14<br />

Anne Hauzeur* & Foni Le Brun-Ricalens. -<br />

Grès et Préhistoire au Luxembourg: Rupture<br />

et continuité dans les stratégies d’implantation<br />

et d’approvisionnement liées aux formations<br />

gréseuses durant le Néolithique (B & L)<br />

Session VI<br />

Chairman: Jan Urban (PL)<br />

Jean Werner*. - Intérêt et richesse de la flore<br />

bryologique du Grès hettangien (Luxembourg,<br />

Eifel et Lorraine) (L)<br />

Olivier Monnier*, Martial Ferréol, Frédéric Rimet,<br />

Alain Dohet, Christophe Bouillon, Henry-Michel<br />

Cauchie, Lucien Hoffmann & Luc Ector. - Le Grès<br />

du Luxembourg: un îlot de biodiversité pour les<br />

diatomées des ruisseaux (L)<br />

Jürgen Jung*. - Sandstone-Saprolite and its relation<br />

to geomorphological processes - examples from<br />

Spessart/Germany as a sandstone-dominated<br />

highland-region (D)<br />

Marie-Claude Auffret* & Jean-Pierre Auffret. -<br />

Similitudes et différences dans l’art rupestre post<br />

glaciaire de Cantabrie (Espagne), Bassin parisien<br />

sud (France), Picardie, Oise et Aisne (Tardenois,<br />

France), Vosges du nord (Bas Rhin et Moselle,<br />

France) et Luxembourg (F)<br />

Session VII<br />

Chairman: Jan Cerovsky (CZ)<br />

Serge Muller*. - Les phytocénoses d’indigénat du<br />

Pin sylvestre (Pinus sylvestris L.) sur les affleurements<br />

de grès du Pays de Bitche (Vosges du Nord)<br />

(F)<br />

Jean-Luc Schwenninger*. - Optical dating of<br />

sand grains: Recent advances and applications in<br />

archaeology and Quaternary research (UK)<br />

Zofia Alexandrowicz & Jan Urban*. - Sandstone<br />

regions of Poland - Geomorphological types,<br />

scientific importance and problems of protection<br />

(PL)<br />

George Dimitriadis*. - A Prehistoric Sandstone<br />

Landscape: Camonica Valley, Italy (I)<br />

Poster session<br />

Session VIII<br />

Chairman: Jean-Marie Sinner (L)<br />

Jonathan Signoret* & Sandrine Signoret. - Les<br />

pineraies à caractère naturel au Grand-Duché de<br />

Luxembourg: caractéristiques, conservation et<br />

suivi (F)<br />

Yves Krippel*. - Is the conservation of the natural<br />

and cultural heritage of sandstone landscapes<br />

guaranteed? Case study of the Petite Suisse area<br />

in Luxembourg (L)<br />

Conference closing<br />

Conference dinner (Hotel Victor Hugo)<br />

Saturday May 28 2005<br />

Post-conference excursion (Teufelsschlucht,<br />

D; Luxembourg-city)<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

G. Frantzen-Heger Allocution de bienvenue<br />

Allocution de bienvenue<br />

Mesdames et Messieurs,<br />

Cette petite ville de Vianden, située aux confins Est<br />

du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, vous souhaite la<br />

plus cordiale bienvenue.<br />

En choisissant Vianden comme lieu du colloque,<br />

vous avez succombé, et c’est compréhensible, à la<br />

double tentation de la nature et tourisme.<br />

La nature d’abord: du point de vue géographique<br />

physique, le Luxembourg ne forme pas une unité<br />

régionale homogène, mais réunit, dans ses étroites<br />

frontières, des fragments d’entités <strong>naturelle</strong>s<br />

auxquelles participent les pays voisins.<br />

La partie méridionale du pays constitue le<br />

prolongement des vallonnements de la plaine<br />

lorraine. Au sud-ouest, le Luxembourg reprend une<br />

bande du gisement de minerai oolithique lorrain.<br />

Au sud-est, il se rattache au domaine viticole de<br />

la Moselle allemande. Sa partie septentrionale,<br />

l’Oesling, et donc notre petite ville de Vianden,<br />

fait partie du massif schisteux rhénan et constitue<br />

un paysage de transition entre l’Eifel allemande et<br />

l’Ardenne belge. Le centre est occupé par le paysage<br />

rupestre et forestier du grès du Luxembourg,<br />

« Sandstone » – le thème de votre colloque, qui, lui<br />

aussi, s’étend au-delà de la frontière orientale.<br />

Empruntant ainsi à des régions <strong>naturelle</strong>s très<br />

diverses, le Luxembourg réunit sur une très faible<br />

étendue territoriale une grande variété de paysages.<br />

C’est là un des secrets de l’attrait qu’il exerce sur<br />

le touriste étranger et l’explication du fait qu’il est<br />

un terrain de prédilection pour les étudiants en<br />

géologie.<br />

Un géographe anglais, George Renwick, a pu dire<br />

qu’ici le grand tome de la nature est condensé en<br />

format de poche.<br />

Il est difficile, en parlant à des professionnels que<br />

vous êtes, de trouver les mots et les définitions<br />

justes pour vanter les beautés de nos sites. Et si,<br />

pour parler avec un poète, qui fut aussi un noble<br />

orateur, il conviendrait peut-être de dire qu’en<br />

pareille occasion «seul le silence est grand».<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Gaby FRANTZEN-HEGER<br />

Bourgmestre, Administration communale de la ville de Vianden<br />

B.P. 10, L-9401 Vianden<br />

bourgmestre@vianden.lu<br />

La voix d’un autre poète me souffle à l’oreille une<br />

sorte d’invocation qui supplée heureusement à mon<br />

inspiration défaillante. Cet autre poète, vous l’avez<br />

deviné, c’est le grand, le majestueux Victor Hugo.<br />

Et cette invocation, la voici, extraite d’une note de<br />

juin 1871 que l’auteur des 'Burgraves' dédia à la cité<br />

de Vianden: «Dans un paysage splendide que viendra<br />

visiter un jour toute l’Europe, Vianden se compose de<br />

deux choses également consolantes et magnifiques,<br />

l’une, sinistre: une ruine, l’autre, riante: un peuple.»<br />

En guise de reconnaissance, la ville de Vianden<br />

a transformé la maison où habitait jadis le grand<br />

homme en musée, le seul musée littéraire du<br />

Grand-Duché, très intéressant à visiter.<br />

On se plait aujourd’hui à voir en Victor Hugo le<br />

précurseur de l’Europe. Il a entrevu des possibilités<br />

de rapprochement des peuples, de l’union<br />

nécessaire de notre continent. Toute l’Europe, vous<br />

la représentez aujourd’hui en ce qu’elle a de plus<br />

avide à connaître.<br />

Le plus illustre visiteur de Vianden parle d’une<br />

chose sinistre: la ruine. Aujourd’hui il n’écrirait plus<br />

ce mot et il puiserait dans son riche vocabulaire<br />

pour chanter les beautés du château palais reconstruit,<br />

un des plus grands et plus beaux bâtiments<br />

des époques romane et gothique de notre Europe,<br />

joyau d’architecture visité annuellement par<br />

quelque 200.000 visiteurs. Et si seulement il avait<br />

pu se servir du télésiège, quelle vue magnifique son<br />

regard d‘aigle aurait embrassé.<br />

A cet égard, Mesdames et Messieurs, vous êtes des<br />

privilégiés par rapport au poète qui, les pieds bien<br />

sur notre terre viandenoise, ne pouvait que monter<br />

nos collines ou se complaire dans les hauteurs de sa<br />

méditation olympienne.<br />

Vianden n’est pas de ces endroits qu’on fait entre<br />

deux trains. Il faut savoir le regarder. Il faut quitter<br />

la grande route et grimper sur les rochers, écouter le<br />

chant de la rivière qui longe ici le centre culturel et<br />

laisser planer ses regards au loin. Il faut aller dans<br />

les ravins boisés, humer le parfum de la bruyère. Et<br />

s’engager dans la grande forêt pour se gonfler les<br />

poumons du souffle de la brise qui murmure dans<br />

les vieux chênes.<br />

15

G. Frantzen-Heger Allocution de bienvenue<br />

16<br />

Après la période d’occupation (lors de la 2ème guerre<br />

mondiale), la petite ville de Vianden a été reconstruite,<br />

adaptée aux exigences modernes, tout en<br />

gardant autant que possible le style médiéval qui<br />

fait de Vianden « La perle du Grand-Duché ».<br />

Il faut emprunter le circuit botanique et le circuit<br />

«extra-muros - intra-muros», visiter l’église des<br />

Trinitaires avec son cloître, le musée d’art rustique<br />

et le musée des poupées, le barrage de l’Our avec<br />

la plus grande centrale hydro-électrique d’Europe,<br />

se détendre à la piscine, avec une magnifique vue<br />

sur le château.<br />

Quant à la chose riante par laquelle le poète<br />

désigne notre peuple, Mesdames et Messieurs, ce<br />

n’est pas à moi de vous en chanter les louanges.<br />

J’espère que vous le connaîtrez par vous-mêmes,<br />

dans une franchise totale et qui permet, je pense,<br />

de nouer de cordiales et durables relations.<br />

C’est au nom de ce peuple viandenois que j’ai<br />

le grand honneur de vous souhaiter une bien<br />

cordiale bienvenue et de formuler tous mes vœux<br />

pour que votre passage à Vianden constitue pour<br />

vous une expérience agréable dans votre colloque<br />

de ces journées.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

J. Werner Discours de bienvenue - Welcome speech<br />

Discours de bienvenue<br />

Madame la bourgmestre, chers collègues,<br />

c’est avec un grand plaisir qu’au nom des organisateurs<br />

je vous souhaite la bienvenue à ce symposium.<br />

En convergeant vers ce joyau des Ardennes, vous<br />

réalisez à votre tour la vision de Victor Hugo, qui a<br />

évoqué Vianden «dans son paysage splendide que<br />

viendra visiter un jour toute l’Europe».<br />

On m’a demandé de faire ce petit discours de<br />

bienvenue alors que l’idée du symposium a germé<br />

au sein du groupe d’études dont je suis le président.<br />

Le botaniste Yves Krippel, un de nos membres les<br />

plus actifs, venait d’assister en septembre 2002,<br />

en République tchèque, au premier congrès interdisciplinaire<br />

de ce genre et il a réussi sans peine<br />

à nous enthousiasmer pour l’organisation d’un<br />

symposium dans notre pays.<br />

Le Luxembourg est prédestiné à accueillir ce<br />

symposium, alors que le Grès hettangien (Jurassique)<br />

affleure sur le cinquième environ de son<br />

territoire, avec notamment la «Petite Suisse<br />

Luxembourgeoise», située à moins de 20 km de<br />

cet endroit! En guise d’introduction je vous dirai<br />

quelques mots sur le «Groupe d’études ayant pour<br />

objet la conservation du patrimoine naturel de la<br />

Petite-Suisse Luxembourgeoise».<br />

Nous sommes en juin 1989. Quelques mois<br />

s’étaient écoulés depuis une mémorable excursion<br />

bryologique qui venait de réunir une trentaine des<br />

plus éminents bryologues du continent, sous la<br />

houlette de mon ami René Schumacker, professeur<br />

à l’Université de Liège. Toutes ces personnes<br />

n’avaient pas quitté la Petite-Suisse sans signer<br />

un appel solennel aux autorités publiques, à fin<br />

qu’elles protègent cette région <strong>naturelle</strong> remarquable<br />

à l’échelle de l’Europe, dont les gorges<br />

et vallées boisées hébergent de nombreuses<br />

bryophytes rares. Comme on n’est souvent pas<br />

prophète dans son pays, il fallait que d’éminents<br />

spécialistes étrangers le clament tout haut! En juin<br />

1989, donc, cet appel fut entendu et le Ministre de<br />

l’Environnement de l’époque, le regretté Robert<br />

Krieps, me demanda de présider un nouveau<br />

groupe d’études qu’il voulait créer. Il me remit<br />

un billet destiné à son administration, portant la<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Jean WERNER<br />

Président du Groupe d’études ayant pour objet la conservation<br />

du patrimoine naturel de la Petite-Suisse luxembourgeoise<br />

Collaborateur scientifique du <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d‘histoire <strong>naturelle</strong><br />

32, rue Michel-Rodange, L-7248 Bereldange<br />

jean.werner@mnhn.lu<br />

phrase laconienne suivante: «Veuillez faire un<br />

règlement pour M. Werner». Au ministère je reçus<br />

évidemment un accueil plutôt glacial, d’autant plus<br />

qu’il restait de nombreux règlements à faire passer<br />

avant les élections imminentes. Je me résignai<br />

alors à rédiger moi-même le texte de droit, lequel<br />

fut, à peine amendé, soumis à la signature du<br />

ministre. Ce dernier promulgua à la même époque<br />

un règlement limitant sévèrement l’escalade<br />

sportive sur les falaises de grès de la région. Il y<br />

eut aussi des échos au niveau communal avec une<br />

résolution du conseil de la ville d’Echternach, la<br />

capitale de la Petite-Suisse, qui reprenait mot à<br />

mot le manifeste des bryologues.<br />

Voilà près de seize ans que le groupe de travail est<br />

actif; il a connu des succès et des déceptions. Parmi<br />

les succès j’évoquerai la fermeture par deux grilles<br />

de la principale gorge à Hymenophyllum et le rôle<br />

de conseil - parfois efficace - que nous avons pu<br />

jouer en matière de mise en œuvre de la Directive<br />

«Habitats» et de quelques autres réglementations<br />

spécifiques. La visite que nous organisons chaque<br />

année pour notre chef d’Etat, Son Altesse Royale<br />

le Grand-Duc Henri, un «aficionado» de la Petite-<br />

Suisse, sont l’occasion de motiver les élus locaux<br />

et de sensibiliser la presse.<br />

Depuis quelques années nous avons élargi notre<br />

champ d’action à la préhistoire. Cet élargissement<br />

nous a beaucoup profité et les nouvelles synergies<br />

qui en résultent sont prometteuses.<br />

Notre groupe n’aurait pas réussi à lui seul<br />

l’organisation d’un congrès. C’est pourquoi il me<br />

faut remercier d’une part les autorités luxembourgeoises<br />

qui en assurent le financement,<br />

et d’autre part les administrations publiques -<br />

Administration des eaux et forêts, <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong><br />

d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong>, <strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire et<br />

d’art- qui ont fait tout le travail logistique. C’est<br />

le moment de dire ma gratitude particulière au<br />

<strong>Musée</strong> <strong>national</strong> d’histoire <strong>naturelle</strong> et plus particulièrement<br />

à son directeur G. Bechet, membre de<br />

notre groupe d’études, et à l’infatigable et inventif<br />

Christian Ries, qui est aussi président de la Société<br />

des naturalistes luxembourgeois. Un grand merci<br />

17

J. Werner Discours de bienvenue - Welcome speech<br />

18<br />

aussi à Madame Gaby Frantzen-Heger, bourgmestre<br />

de Vianden, pour avoir mis à notre disposition<br />

ces splendides locaux !<br />

Ladies and gentlemen, dear colleagues,<br />

I wish you a pleasant stay in this romantic little<br />

town. I am sure that you will enjoy the lectures<br />

and the posters, which cover such diverse subjects<br />

as botany, zoology, conservation, prehistoric<br />

dwellings and art. They pertain not solely to the<br />

sandstone rock itself, but also to the whole natural<br />

landscape, with forests and streams.<br />

Our colleague Andy Jackson, a bryologist from<br />

Kew Gardens, reminded us in a recent paper that<br />

extensive sandstone landscapes, at low altitude,<br />

are rare within the European Continent: He<br />

mentions the Weald in SE England (where he is<br />

active himself), the Petite-Suisse Luxembourgeoise,<br />

the Bohemian-Saxon sandstone area, and<br />

the Forêt de Fontainebleau; he could have added<br />

some other areas like the Northern Vosges, some<br />

parts of Rheinland-Pfalz etc. It is urgent to set up a<br />

complete list of all those areas, indeed!<br />

But, while fostering a better scientific understanding,<br />

one should not forget public action at a<br />

European level. Un updated version of "Habitats"<br />

Directive, for instance, should hopefully refer,<br />

in its annexes, more explicitly to those precious<br />

sandstone rock ecosystems.<br />

Let us hope that those who make environmental<br />

decisions in Europe will read the proceedings<br />

of this symposium. Conservation issues are<br />

often perceived as a nuisance in a society just<br />

preoccupied by material success and efficiency.<br />

Beyond those many rational arguments which<br />

can be put forth to preserve sandstone rock,<br />

there is something which cannot be proved just<br />

at the level of rational thinking: It is the Beauty<br />

of nature and the happiness it can give to many<br />

people. The mossy, pink or yellow sandstone<br />

scenery of Luxembourg Petite Suisse or of the<br />

Vosges area, surrounded by beeches or conifers,<br />

eventually embellished by prehistoric pictograms,<br />

against a clear blue summer sky, is indeed simply<br />

beautiful.<br />

I thank you for your attention.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Oral communications<br />

Communications orales<br />

19

20<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

J. Adamovič Sandstone cementation and its geomorphic and hydraulic implications<br />

Sandstone cementation and its geomorphic and<br />

hydraulic implications.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Jiří ADAMOVIČ<br />

Institute of Geology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic<br />

Rozvojová 135, CZ-165 02 Praha 6<br />

adamovic@gli.cas.cz<br />

Keywords: Sandstone; Siliceous cement; Carbonate cement; Ferruginous cement; Paleohydraulics;<br />

Geomorphology; Sandstone landforms<br />

Introduction<br />

Mineral cement is the most important intrinsic<br />

factor in estimating erosion rates in sandstone<br />

regions. Its composition is a function of mineral<br />

availability in the basin and burial/thermal history<br />

of the basin. Post-depositional tectonic setting of<br />

particular segments of the basin may then control<br />

cement distribution, especially through differential<br />

fluid circulation. Most cemented sandstones<br />

are relatively resistant to weathering in outcrops,<br />

giving rise to a variety of forms of positive relief.<br />

In the subsurface, however, where flushing rate is<br />

higher, silica and carbonate cements get readily<br />

dissolved producing large volumes of easily<br />

eroded loose sand. Impressive solutional forms<br />

in quartzite can be observed in tropical (Chalcraft<br />

& Pye 1984), subtropical (Busche & Erbe 1987) as<br />

well as temperate (Battiau-Queney 1984) climatic<br />

zones, and quartz dissolution is considered a<br />

process playing a major role in the karstification<br />

of even weakly cemented quartzose sandstones<br />

worldwide (Wray 1997).<br />

Silica cement<br />

The very low solubilities of quartz at normal pH<br />

and temperature (~5 ppm) rapidly increase with<br />

increasing pH values, especially above the pH of<br />

9.83 which corresponds to the first dissociation<br />

constant of silicic acid (Eby 2004), reaching values<br />

of >20 ppm at pH 10 and 25 °C. Comparable<br />

solubilities of quartz can be also achieved by rising<br />

temperature: at normal pH, 20 ppm SiO 2 (quartz)<br />

dissolve at temperatures of around 50 °C. Solubilities<br />

of cryptocrystalline and amorphous silica are<br />

by one order of magnitude higher than those of<br />

crystalline quartz. Laboratory experiments are<br />

consistent with observations from deeply buried<br />

sandstones where secondary quartz overgrowths<br />

typically appear on detrital quartz grains at<br />

depths of over 1 km and temperatures of over<br />

40 °C (McBride 1989). The main source of diagenetic<br />

silica is pressure solution at grain contacts<br />

and stylolites, and conversion of primary clay<br />

minerals due to sediment burial.<br />

Where rapid silica precipitation takes place,<br />

chalcedony and opal are the dominant phases.<br />

This is the case of hydrothermally mobilized SiO 2<br />

in areas of siliceous hot springs (Guidry & Chafetz<br />

2003) or near contacts of sandstone with volcanic<br />

bodies.<br />

A wide range of silica phases are present in<br />

silcretes, products of surface and near-surface<br />

diagenesis generally conforming to surface topography<br />

and formed either within a weathering<br />

profile or at stable groundwater levels. Silica<br />

mobilization in such settings (normal pH and<br />

low temperatures) is explained by high flushing<br />

rates over a prolonged time. The best known<br />

silcrete examples in Europe are the Fontainebleau<br />

sandstone in France (Thiry et al. 1988) and the<br />

sarsen and puddingstone sandstones of southern<br />

England (Hepworth 1998).<br />

Carbonate cement<br />

Unlike silica, carbonates can be transported in<br />

solutions of low pH and low temperature. Calcite,<br />

dolomite and siderite cements generally form<br />

patchy, strata-bound bodies in the sandstone, or<br />

isolated concretions. CaCO 3 is mostly derived from<br />

shells and skeletal remains of fossil organisms, or is<br />

precipitated directly from pore waters. Carbonate<br />

cement is of early diagenetic origin, and its precipitation<br />

predates deeper sediment burial.<br />

21

J. Adamovič Sandstone cementation and its geomorphic and hydraulic implications<br />

22<br />

Ferruginous cement<br />

Iron is mobile in its bivalent form, in environments<br />

of low redox potential. In oxidative environments,<br />

within the reach of meteoric waters, ferrous iron<br />

turns into ferric iron which is difficult to mobilize,<br />

unless by fluids of very low pH.<br />

Red colouration of sandstones (commonly referred<br />

to as red beds) indicates the presence of ferric iron:<br />

dispersed goethite/limonite after weathering of<br />

iron-rich detrital minerals, which gets transformed<br />

into hematite grain coatings after burial-induced<br />

goethite dehydration. Small amounts of cement<br />

in the red-beds sandstones have, however, only a<br />

weak effect on their permeability or geomorphic<br />

expression. Massive filling of pores in sandstone<br />

by hematite and/or goethite to form sheet-like,<br />

tube-like and spherical concretionary bodies of<br />

ferruginous sandstone is caused by fault-parallel<br />

circulation of saline fluids and hydrocarbons in<br />

the red-beds sandstones (Navajo Sandstone, Utah<br />

- Chan et al. 2000) or fluids laden with Fe 2+ from the<br />

adjacent volcanic bodies (Bohemian Cretaceous<br />

Basin, Czech Republic - Adamovič et al. 2001).<br />

Lateritic horizons are formed by in situ chemical<br />

weathering of rocks under tropical humid<br />

conditions favouring removal of alkalis, alkali<br />

earths and silicon and enrichment in iron and<br />

aluminium. A related term ferricrete was introduced<br />

for surface sands and gravels cemented<br />

into a hard mass by iron oxide derived from the<br />

oxidation of percolating solutions of iron salts.<br />

The process of pedogenic laterite formation is<br />

equivalent to podzolization in temperate humid<br />

regions, leading to the formation of Ortstein.<br />

Cementation and permeability<br />

Less permeable sheet-like and concretionary<br />

bodies of early cemented sandstone tend to be<br />

elongated parallel to the groundwater flow and<br />

are often hosted by pre-existing higher-permeability<br />

fault and fracture zones. This way, early<br />

cementation may control the direction of later<br />

fluid flow and seal the tectonically predisposed<br />

paths of fluid ascent from the basement rocks. A<br />

series of drawings in Fig. 1 schematically illustrates<br />

a progressive hydraulic compartmentation<br />

of a sandstone-filled basin after three consecutive<br />

episodes of cementation.<br />

Porosity reduction due to quartz and chalcedony<br />

cementation of quartzose sandstone has been<br />

documented at Milštejn, northern Bohemian<br />

Cretaceous Basin, Czech Republic (Adamovič &<br />

Kidston 2004). Total porosity was measured on<br />

a profile transverse to a phonolite dyke, which<br />

supplied alkaline fluids responsible for silica<br />

redistribution. A 12 m broad proximal zone of<br />

secondary porosity due to quartz dissolution<br />

(limited outcrops but large cavities nearby) passes<br />

to a 3–5 m broad zone where porosity drops to<br />

5 % due to grain compaction, pressure solution<br />

and microquartz precipitation. Lenses 0.2 m thick<br />

of chalcedonized sandstone with only 0.5 % total<br />

porosity follow a subvertical brecciation zone. At<br />

22 m from the dyke, porosity increases to 25 % in a<br />

sandstone with occasional quartz overgrowths.<br />

Cementation and morphology<br />

Cemented sandstones are generally more resistant<br />

to weathering and form positive relief. Large<br />

cementation-induced landforms include plateaus<br />

and table mountains, ridges and walls. Rock<br />

mushrooms, arches and bridges with tops of<br />

cemented sandstone are the typical landforms on<br />

plateau rims. Microforms like ledges, knob- and<br />

tube-shaped protrusions as well as fine sculptation<br />

on rock walls are generally controlled by<br />

uneven cement distribution and the presence<br />

of concretions. In contrast, silicified sandstones<br />

shaped by silica dissolution tend to form negative<br />

relief (spherical cavities, caves) and have the<br />

appearance of karst forms in carbonate rocks.<br />

Parallels with carbonate karst also exist in the<br />

presence of accumulation forms of silica speleothems<br />

(Wray 1999).<br />

In the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin, uneven<br />

cementation of thick bodies (>100 m) of quartzose<br />

sandstone with iron oxyhydroxides and silica<br />

results from their interaction with intrusive and<br />

effusive bodies of volcanic rocks, and produces a<br />

variety of landforms of various size (Müller 1928;<br />

Adamovič et al. 2001; Adamovič & Cílek 2002).<br />

The research was conducted within Project<br />

A3013302 of the Grant Agency of the Academy of<br />

Sciences of the Czech Republic.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

J. Adamovič Sandstone cementation and its geomorphic and hydraulic implications<br />

Fig. 1: A model example of the evolution of a sand-dominated sedimentary basin subjected to three stages of cementation.<br />

A. Sandstone packages thin away from the tectonically active basin margin on the right (source area),<br />

with conglomerate beds and shell layers preserved on sequence boundaries/flooding surfaces. B. Compaction of<br />

the basin fill is accompanied by formation of poikilotopic calcite cement in shell layers. C. Tectonic reactivation<br />

results in pulses of iron-rich fluids from the basement rocks and precipitation of ferruginous cement in high-permeability<br />

zones. D. Tectonic subsidence of the basin produces silica cementation along faults and in deeper-buried<br />

parts of the basin (quartz overgrowts). E. After tectonic inversion and emergence of the basin fill, cemented<br />

sandstones show higher resistance to weathering and erosion. Note the increasing compartmentation of the basin<br />

during its evolution, restricting the fluid circulation.<br />

References<br />

Adamovič J. & Cílek V. (eds.) 2002. - Železivce<br />

české křídové pánve. Ironstones of the<br />

Bohemian Cretaceous Basin. Knihovna ČSS 38:<br />

146-151. Praha.<br />

Adamovic J. & Kidston J. 2004. - Porosity reduction<br />

in coarse detrital rocks along dike contacts:<br />

evidence from basaltic and phonolitic dikes.<br />

AAPG European Region Conference with GSA,<br />

October 10-13, 2004, Prague. Official Program<br />

& Abstract Book, 56. Praha.<br />

Adamovič J., Ulrych J. & Peroutka J. 2001. - Geology<br />

of occurrences of ferruginous sandstones in<br />

N Bohemia: famous localities revisited. Geol.<br />

Saxonica – Abh. Mus. Miner. Geol. Dresden<br />

46/47: 105-123.<br />

Battiau-Queney Y. 1984. - The pre-glacial evolution<br />

of Wales. Earth Surf. Proc. Landf. 9: 229-252.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Busche D. & Erbe W. 1987. - Silicate karst landforms<br />

on the southern Sahara, northeastern Niger<br />

and southern Libya. Z. Geomorphol. (Suppl.)<br />

64: 55-72.<br />

Chalcraft D. & Pye K. 1984. - Humid tropical<br />

weathering of quartzite in southeastern<br />

Venezuela. Zeitschr. Geomorphologie 28: 321-<br />

332.<br />

Chan M.A., Parry W.T. & Bowman J.R. (2000):<br />

Diagenetic hematite and manganese oxides and<br />

fault-related fluid flow in Jurassic sandstones,<br />

southeastern Utah. AAPG Bull. 84: 1281-1310.<br />

Eby G. N. 2004. - Principles of environmental<br />

geochemistry. Thomson Brooks/Cole, Pacific<br />

Grove, 514 p.<br />

Guidry S. A. & Chafetz H. S. 2003. - Anatomy of<br />

siliceous hot springs: examples from Yellowstone<br />

National Park, Wyoming, USA. Sed.<br />

Geol. 157: 71-106.<br />

23

J. Adamovič Sandstone cementation and its geomorphic and hydraulic implications<br />

24<br />

Hepworth J. V. 1998. - Aspects of the English<br />

silcretes and comparison with some Australian<br />

occurrences. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 109: 271-288.<br />

McBride E. F. 1989. - Quartz cement in sandstone:<br />

a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 26: 69-112.<br />

Müller B. 1928. - Der Einfluss der Vererzungen<br />

und Verkieselungen auf die Sandsteinlandschaft.<br />

Firgenwald 1: 145-155.<br />

Thiry M., Ayrault M. B. & Grisoni J.-C. 1988. -<br />

Ground-water silicification and leaching in<br />

Résumé de la présentation<br />

Le liant du grès et ses implications géomorphologiques et hydrauliques<br />

Les ciments siliceux, ferrugineux et de carbonate sont<br />

les constituants secondaires les plus communs des grès,<br />

remplissant souvent <strong>complète</strong>ment tous les espaces<br />

intergranulaires. La présence du ciment minéral rend<br />

nécessaire, d’une part, une source interne ou externe au<br />

bassin sédimentaire des éléments requis, d’autre part,<br />

la mobilisation des fluides de chimisme appropriée, du<br />

pH, et de la température pour transporter ces éléments.<br />

Et en final, rend nécessaire, la mise en place des conditions<br />

physico-chimiques dans la fenêtre de stabilité des<br />

minéraux de cimentage particuliers au bassin sédimentaire.<br />

La variété des ciments minéraux dans les grès est une<br />

fonction du chimisme du fond du bassin, de la présence<br />

de corps intrusifs et extrusifs à proximité du bassin, et<br />

de l’histoire tectonique du bassin, particulièrement la<br />

profondeur d’enfouissement du sédiment.<br />

Après enfouissement profond (à des profondeurs<br />

supérieures à 2,5 km), les minéraux primaires d’argile<br />

de même que les grains détritiques de quartz sont<br />

modifiés en silice mobile. La précipitation de cette silice,<br />

la plupart du temps sous forme de croissance syntaxial<br />

de quartz sur des grains de quartz eux-mêmes peut<br />

mener à la diminution importante de porosité sur de<br />

grands volumes de grès enfouis. Une faible dissolution<br />

du quartz, se produit même à des températures et des<br />

pressions beaucoup plus basses, comme mis en évidence<br />

par la silicification de grès le long des corps des roches<br />

volcaniques alcalines et par des exemples multiples de<br />

karst de quartzite partout dans le monde. Le ciment de<br />

carbonate a la plupart du temps une provenance interne<br />

au bassin, dérivé des coquilles de mollusque mises en<br />

solution lors des premières étapes de la diagenèse du<br />

sands: example of the Fontainebleau Sand<br />

(Oligocene) in the Paris Basin. Geol. Soc. Amer.<br />

Bull. 100: 1283-1290.<br />

Wray R. A. L. 1997. - A global review of solutional<br />

weathering forms on quartz sandstone. Earth<br />

Sci. Rev. 42: 137-160.<br />

Wray R. A. L. 1999. - Opal and chalcedony speleothems<br />

on quartz sandstones in the Sydney<br />

region, southeastern Australia. Austr. J. Earth<br />

Sci. 46: 623-632.<br />

Mots-clés: Grès; Ciment silicieux; Ciment de carbonate; Ciment ferrugineux; Paléohydraulique;<br />

Géomorphologie; Reliefs de paysages de grès<br />

sédiment. Les sources du fer pour le ciment ferrugineux<br />

peuvent être multiples, s’étendant des minéraux détritiques<br />

riches en fer présents dans le bassin aux roches<br />

encaissantes mafiques (foncées).<br />

Comme la distribution du ciment est commandée par<br />

le flux de fluide dans le bassin, les corps concrétionnés<br />

ou en forme de feuillet du grès cimenté tendent à être<br />

allongés parallèlement au paléoflux des eaux souterraines<br />

et sont souvent accueillis par des zones de faille<br />

ou de fracture de haute perméabilité. Le ciment précoce<br />

réduit la porosité du grès, et de ce fait, limite les mouvements<br />

de liquide dans le bassin en soutenant une modification<br />

du compartimentage hydraulique.<br />

Les grès cimentés sont généralement plus résistants à<br />

l’altération et forment des reliefs positifs. Les formes de<br />

relief de ces cémentation induites sont de diverses tailles,<br />

depuis des plateaux et des ‘montagne-table’, arêtes et<br />

murs, rebords de roche en forme de champignons, de<br />

bouton et de tube comme autant de fines sculptures dans<br />

les murs de roche. Beaucoup de formes de relief dans les<br />

grès silicifiés ont été dessinées par la dissolution de silice<br />

et partagent le caractère des formes de karst des roches<br />

carbonatées.<br />

Les principes donnés peuvent être illustrés par des<br />

exemples de, par exemple, des paysages tempérés de la<br />

République Tchèque et de l’Angleterre ou des paysages<br />

arides du sud-ouest américain.<br />

Cette recherche fut menée dans le cadre du projet<br />

A3013302 de l’office des subsides de l’Académie des<br />

sciences de la République Tchèque.<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

J. Juilleret et al. Soutien des débits d’étiage par l’aquifère du Grès du Luxembourg<br />

Soutien des débits d’étiage des cours d’eau du<br />

grand-duché du Luxembourg par l’aquifère du<br />

Grès du Luxembourg<br />

Ferrantia • 44 / 2005<br />

Jérôme JUILLERET, Fabrizio FENICIA, Patrick MATGEN, Cyrille TAILLIEZ,<br />

Lucien HOFFMANN & Laurent PFISTER<br />

Cellule de Recherche en Environnement et Biotechnologies<br />

Centre de Recherche <strong>Publi</strong>c-Gabriel Lippmann<br />

41, rue du Brill, L-4422 Belvaux<br />

juillere@lippmann.lu<br />

Mots-clés: débits spécifiques d’étiage; Grès du Luxembourg; bassin versant; lithologie; aquifère<br />

Introduction<br />

Au Luxembourg, la tendance pour l’avenir à<br />

des étés plus chauds et plus secs (Drogue et al.<br />

2005) souligne la vulnérabilité des rivières et<br />

des aquifères tant quantitativement que qualitativement.<br />

Le réseau hydrographique luxembourgeois<br />

appartient en quasi-totalité au bassin<br />

versant de la Sûre qui traverse le pays depuis la<br />

frontière belgo-luxembourgeoise au nord-ouest<br />

vers l’est où elle rejoint la Moselle à Wasserbillig.<br />

A l’amont d’Ettelbrück, la Sûre s’écoule sur le<br />

substrat principalement schisteux de la région<br />

<strong>naturelle</strong> de l‘Oesling. L’Alzette qui conflue avec<br />

la Sûre à Ettelbrück draine l’autre région <strong>naturelle</strong><br />

appelée Gutland, où les principales lithologies<br />

sont des alternances marno-calcaro-gréseuses et le<br />

Grès du Luxembourg.<br />

Le réseau de mesure de débits mis en place par le<br />

Centre de Recherche <strong>Publi</strong>c- Gabriel Lippmann et<br />

l’Administration de la Gestion de l’Eau enregistre<br />

les débits journaliers de la Sûre et de ses affluents.<br />

Le débit étant tributaire d’une part des eaux<br />

souterraines et d’autre part du ruissellement lié<br />

à la nature lithologique ainsi qu’aux sols (Pfister<br />

et al. 2002) il est possible d’analyser les hydrogrammes<br />

à la lumière de la nature du substrat du<br />

bassin versant. Le but de cette étude est de mettre<br />

en évidence l’influence des différentes lithologies<br />

sur le débit de manière générale et le rôle des Grès<br />

du Luxembourg en particulier.<br />

Méthodologie<br />

L’analyse du régime hydrologique est basée<br />

sur les hydrogrammes de débits spécifiques<br />

estivaux des années 2003 et 2004 ainsi que sur<br />

l’analyse des courbes de récession des débits.<br />

Les hydrogrammes ont été dressés à partir des<br />

débits journaliers enregistrés aux stations hydrométriques<br />

de Winseler pour la Wiltz, Hagen et<br />

Hunnebour pour l’Eisch et Mamer et Schoenfels<br />

pour la Mamer. Le débit spécifique rapporté<br />

à la superficie du bassin versant, exprimé en<br />

l.s -1 .km -2 permet de comparer les débits des<br />