By Ariefrahman, CC BY-SA 4.0

Etymology: Great Head

First Described By: Müller, 1846

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Megapodiidae

Status: Extant, Endangered

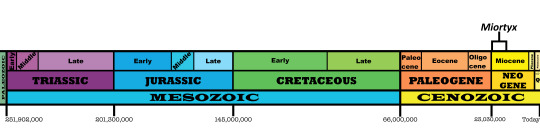

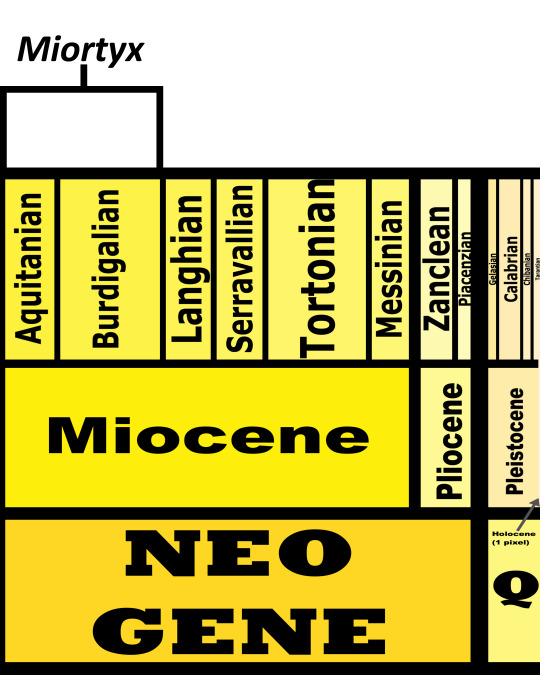

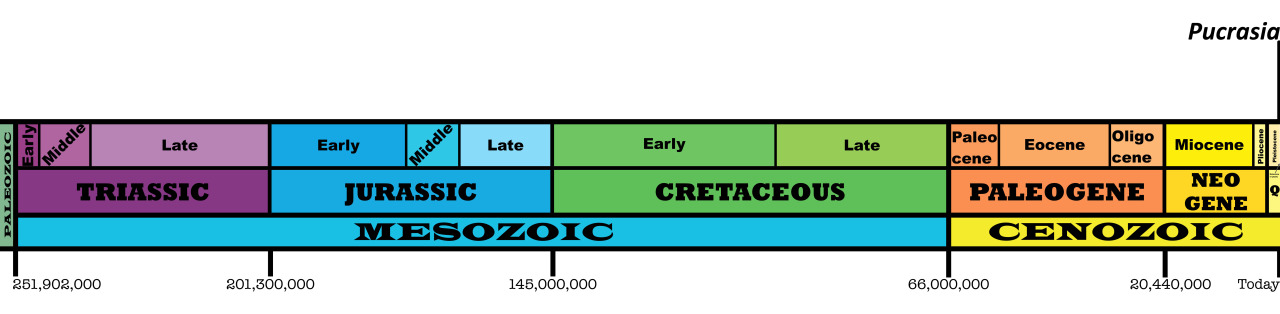

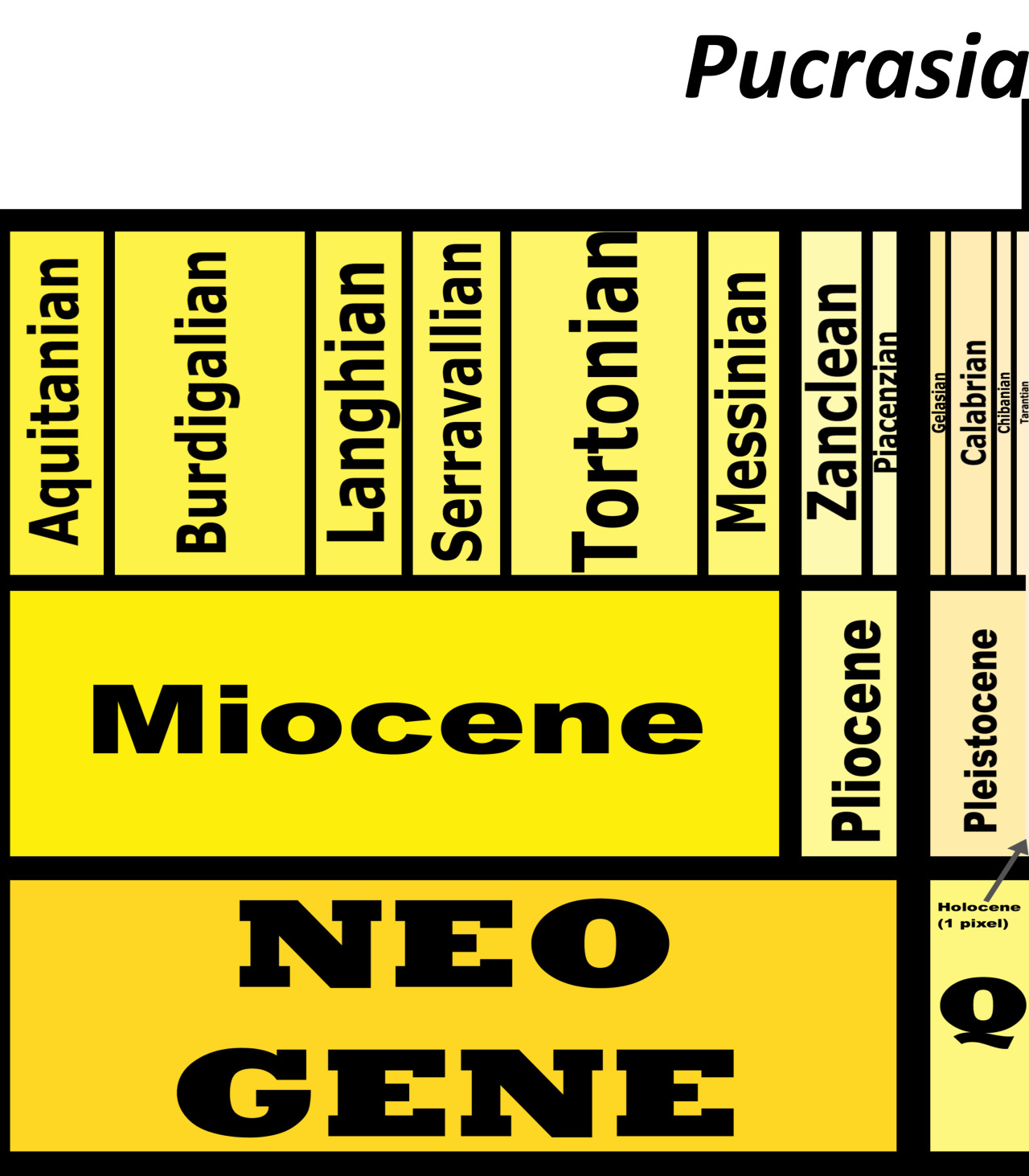

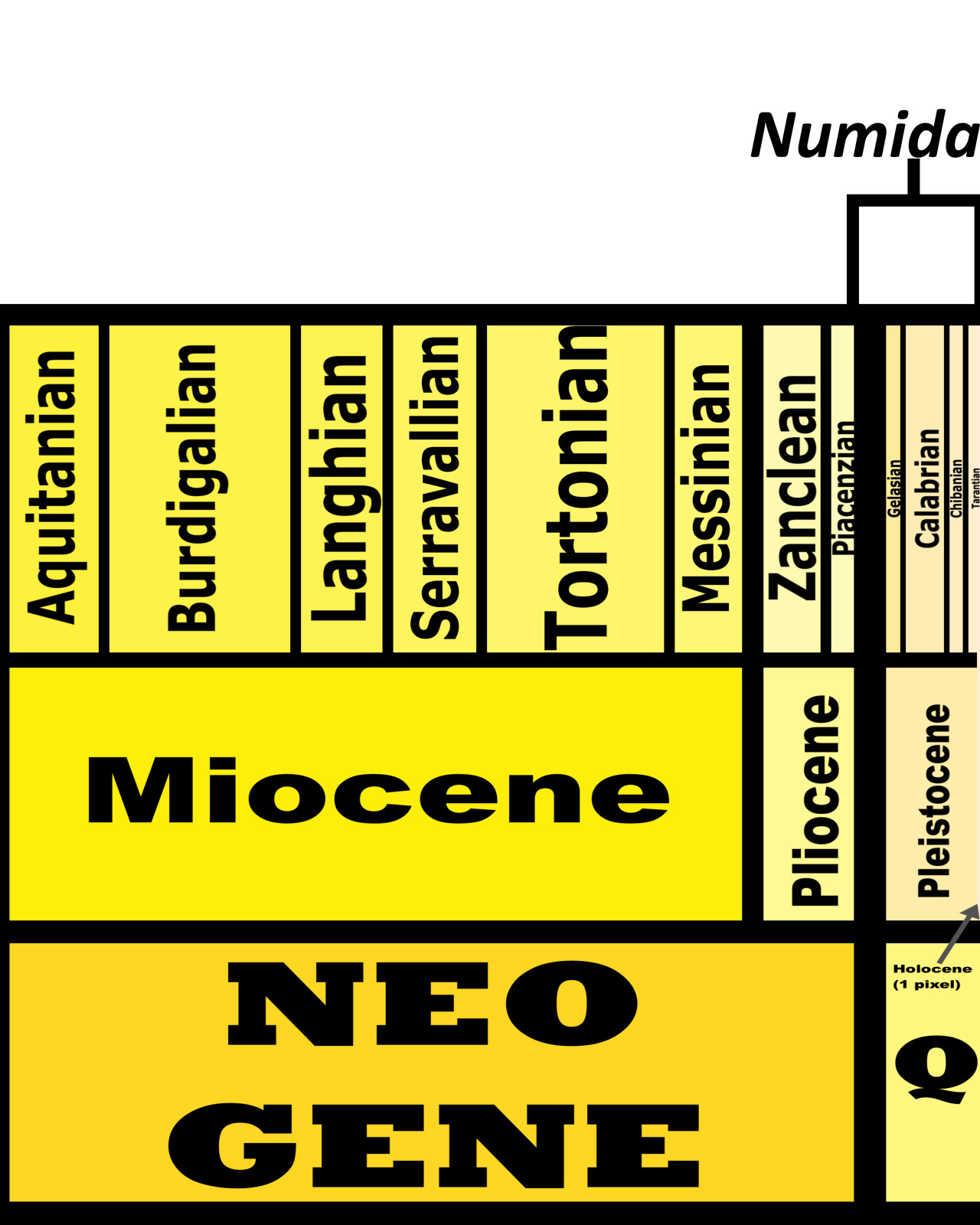

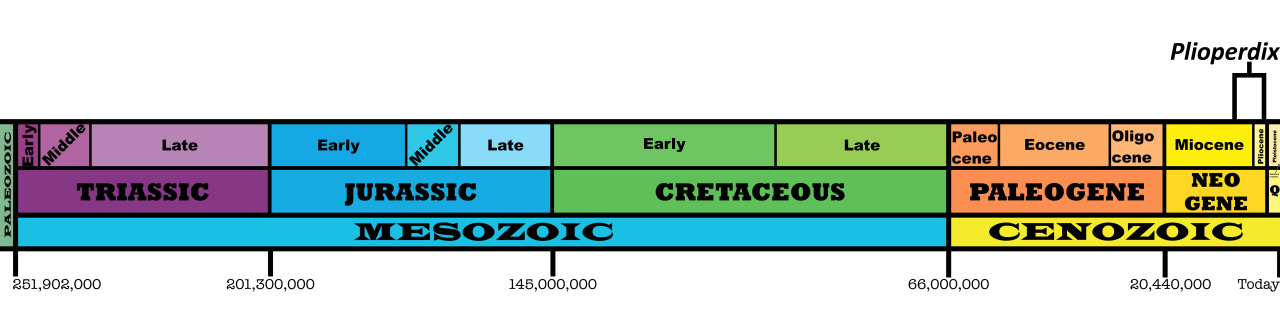

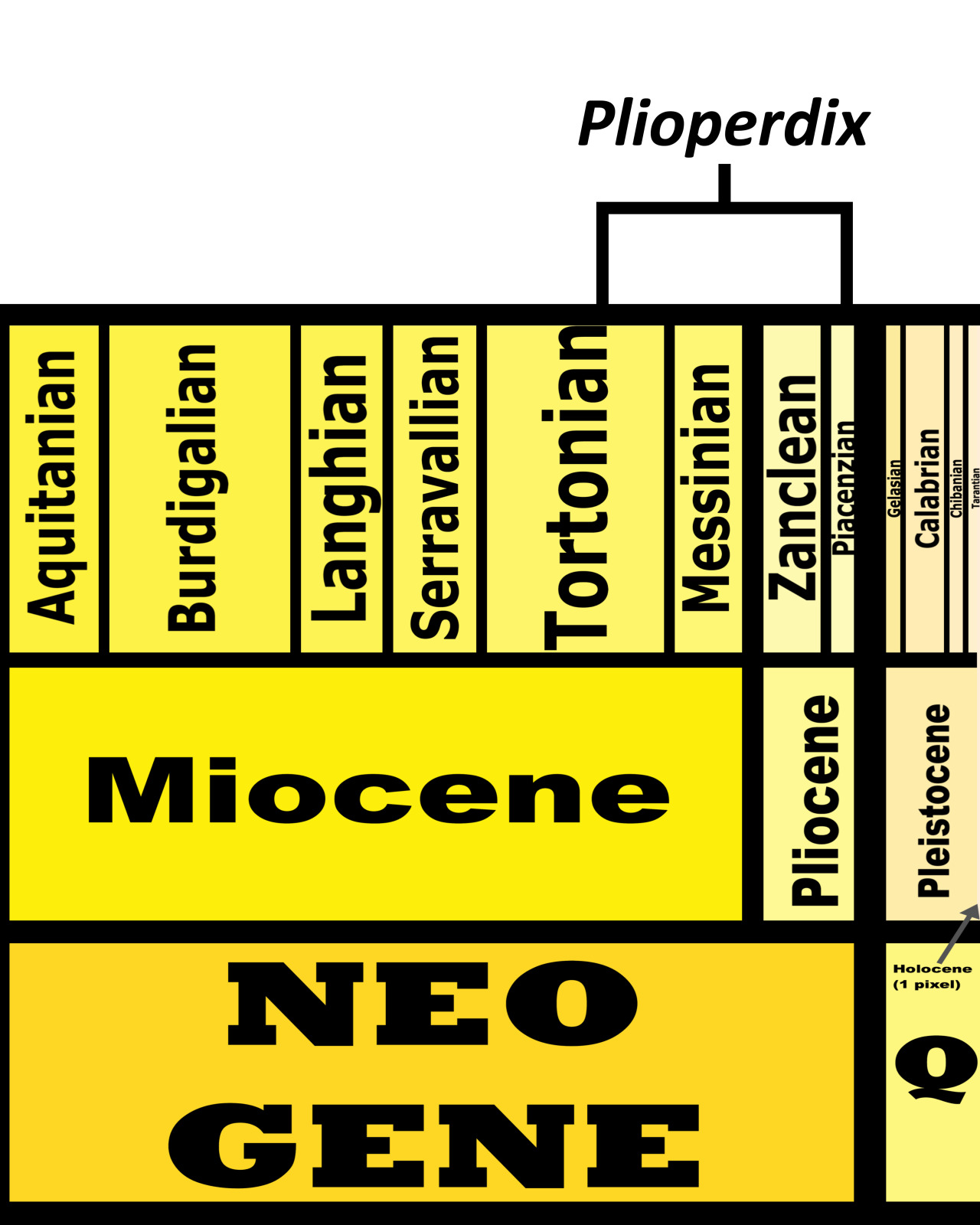

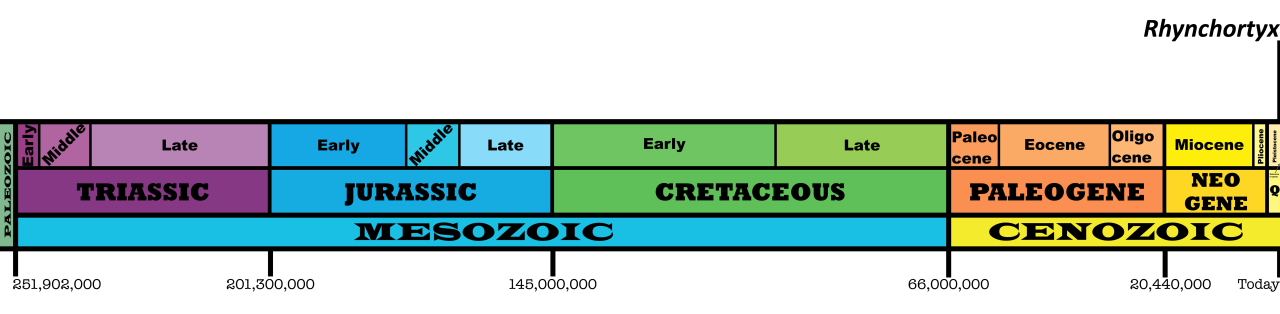

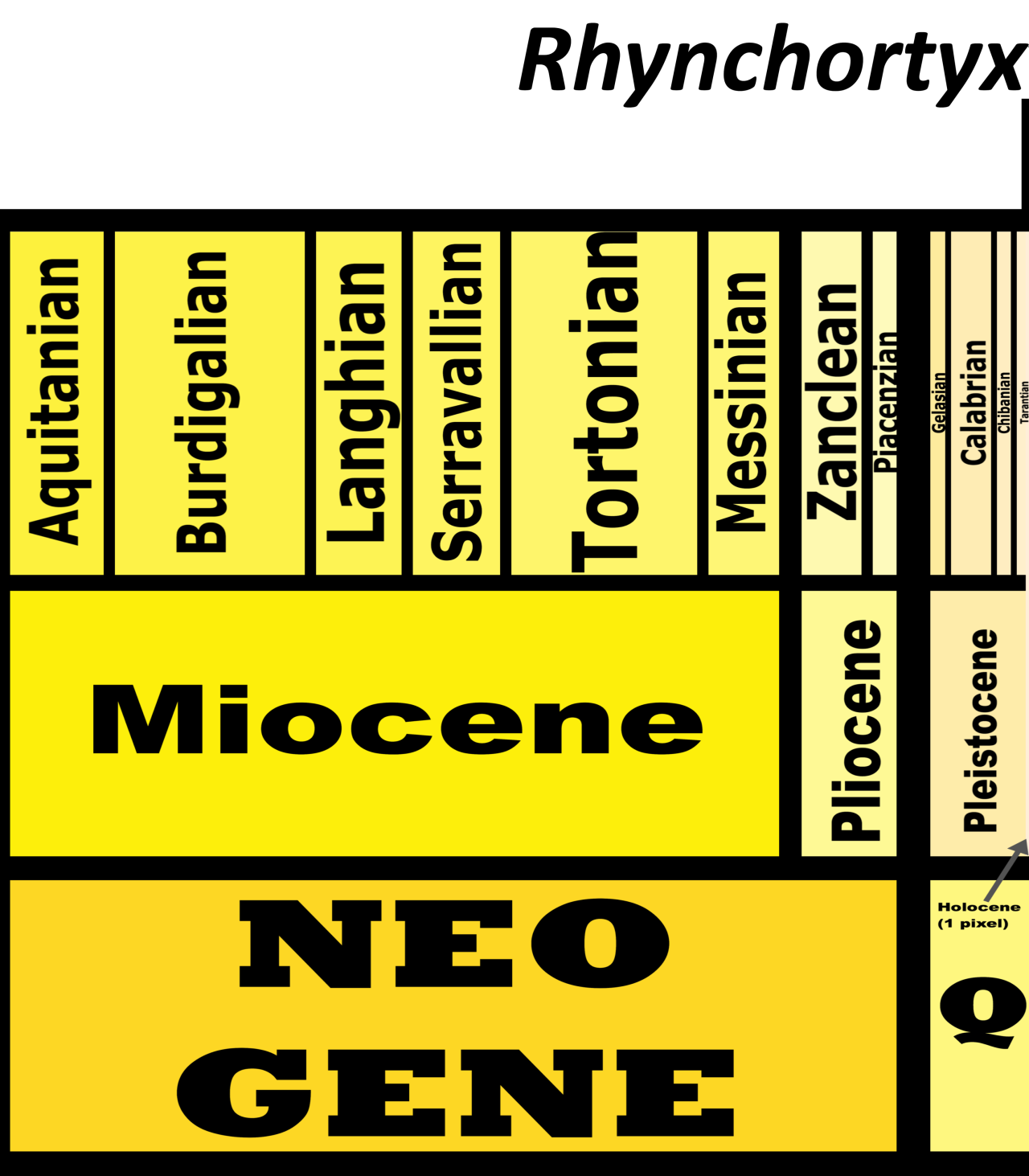

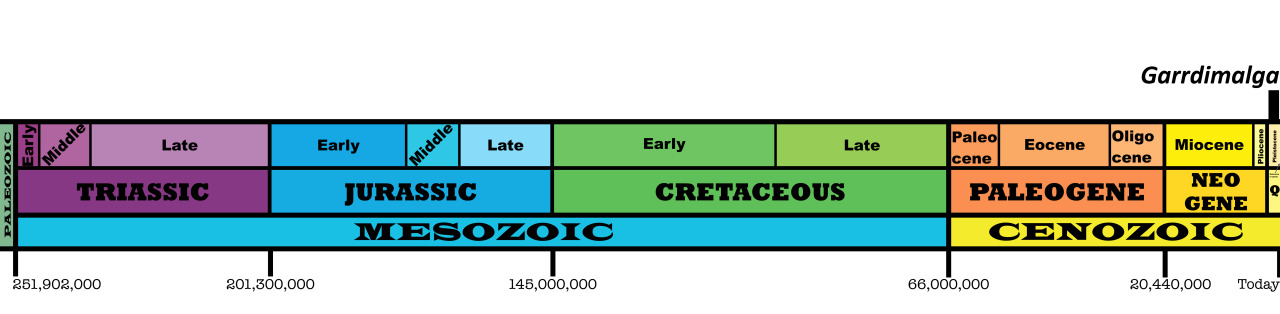

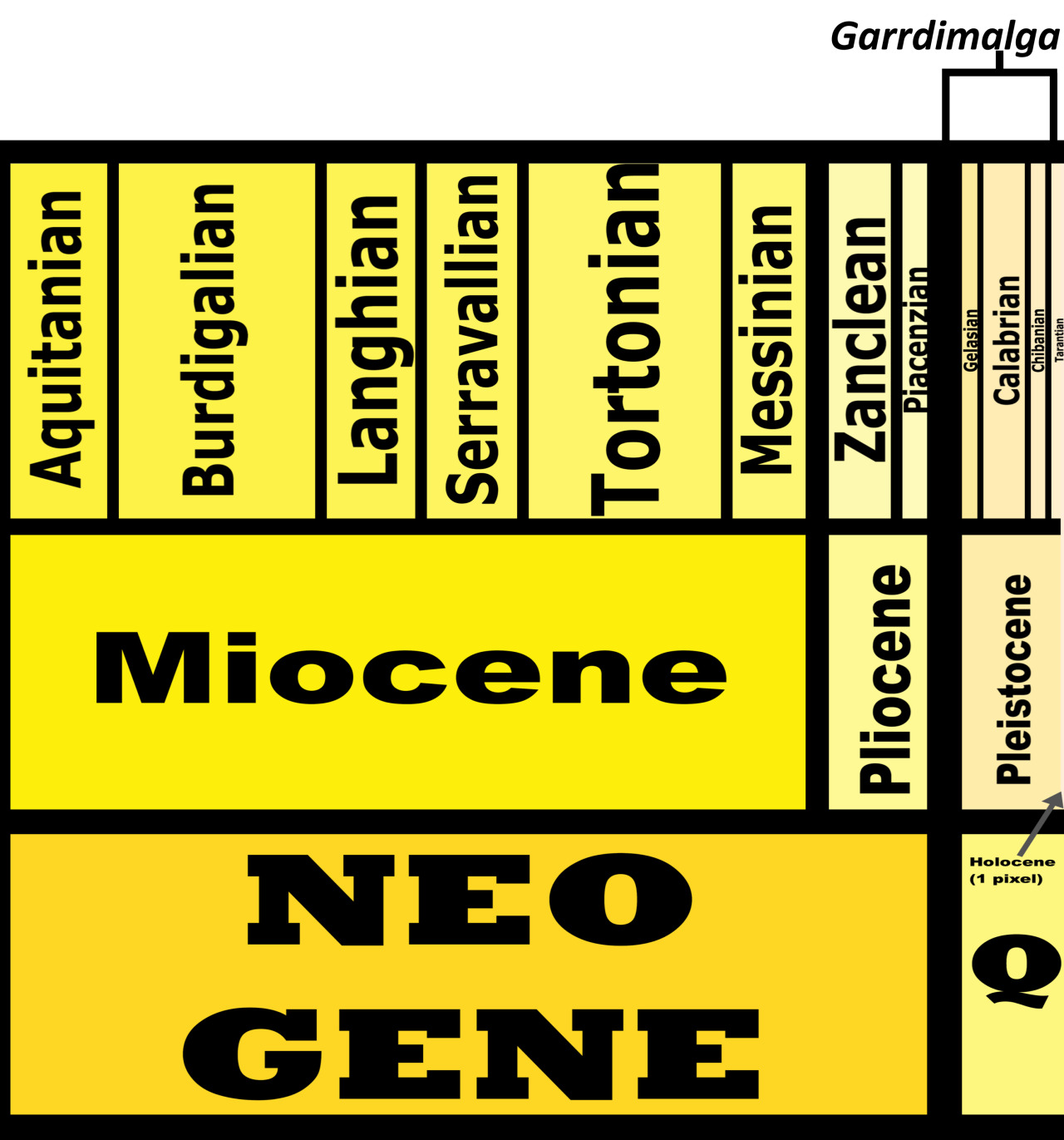

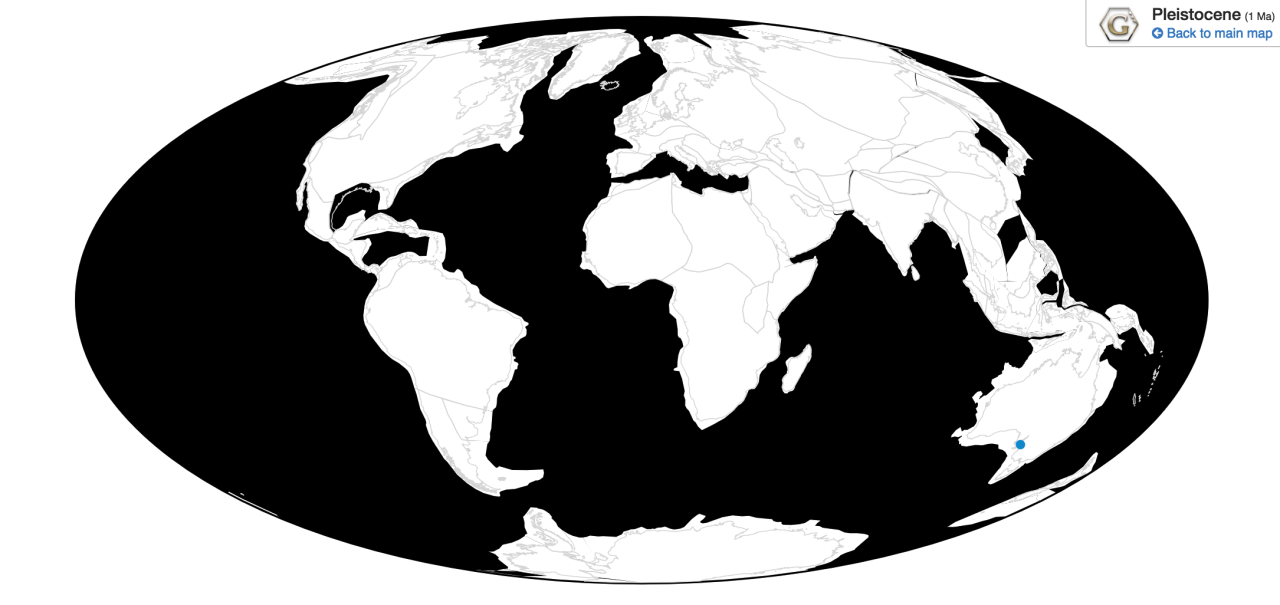

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

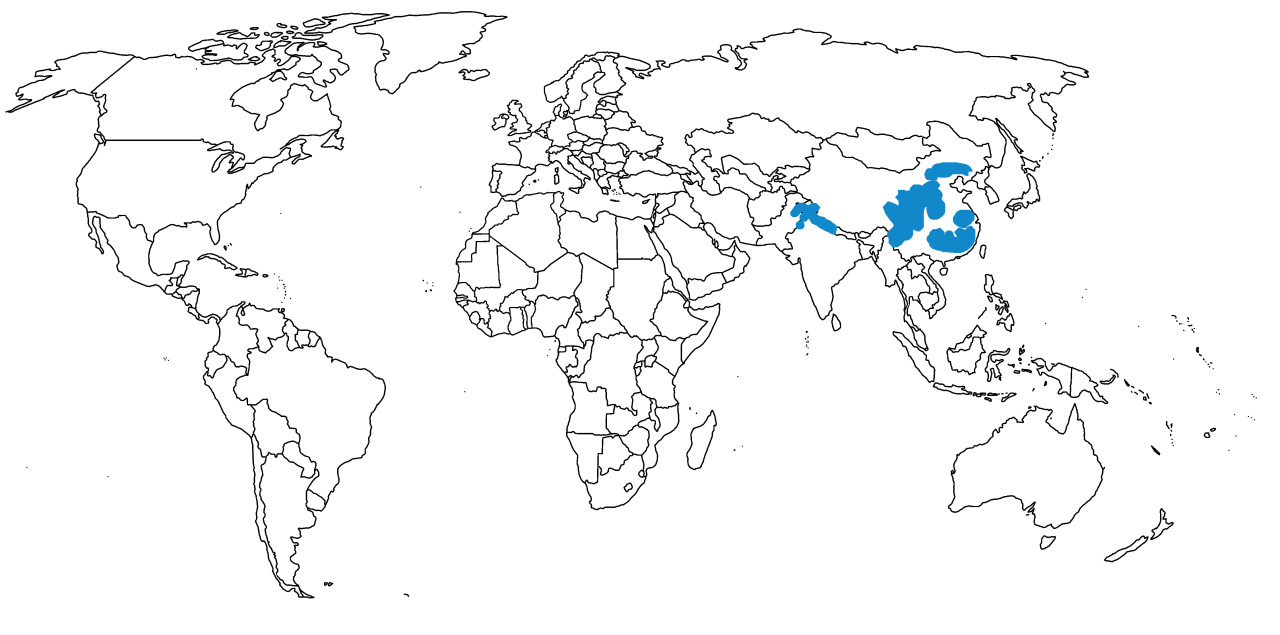

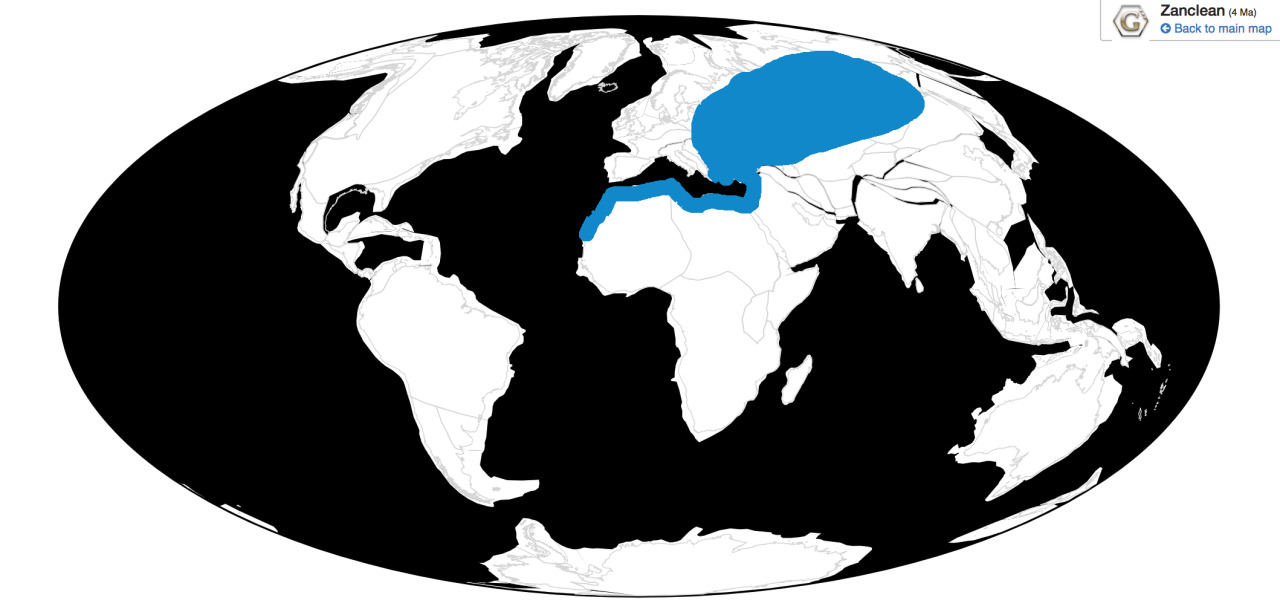

Maleos are known entirely from the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia

Physical Description: Maleos are large landfowl, reaching 55 centimeters in length. These are large, round birds with skinny necks and odd looking heads – they have black crests on the tops of their heads that flop over the back, and little red bands at the top of their beaks. The beaks of Maleos are thick and grey, and they have primarily brown heads. Their backs are black, as are their wings and tails, but their bellies are white; and they have long, grey legs. In addition to all of this, Maleos have orange rings around their eyes that are extremely noticeable. The young tend to have black heads in addition to these features.

Diet: Maleos feed on a variety of fruits, seeds, insects, and other invertebrates.

By Stavenn, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Maleos are Megapodes, which means they are one of the only groups of dinosaurs that don’t take care of their young! Instead, Megapodes make giant mound-nests which use geothermal energy and solar-heat in order to incubate the eggs. Maleos are monogamous, mating with only one individual per season (and potentially per life, but they aren’t very well studied), and the pair builds the nest mound together, lays the eggs, and leaves. Around ten eggs are laid per year, though some may lay as many as thirty. The eggs incubate for nearly three months; when the young hatch, they rapidly lose a lot of weight, before beginning to chow down on as much food as possible and growing rapidly for the next two months. They reach sexual maturity themselves at around two years of age. They can live for up to 23 years.

By BronxZooFan, CC BY-SA 4.0

These are noisy birds, making a wide variety of calls including brays, rolls, and quacking – to the point of sounding rather surreal in some situations. They tend to spend most of their time foraging with their mate, walking around and gathering the food off of the ground. They do not migrate, but they also do move around the island each year, not sticking in one place or placing their nests in the same sites from year to year.

Ecosystem: These megapodes live primarily in lowland and hill jungle, going to the beaches for their breeding or in forest clearings with extensive amounts of sand. They usually roost in trees high off of the ground. Maleos are preyed upon by humans, pigs, monitor lizards, and crocodilians.

By Ariefrahman, CC BY-SA 4.0

Other: Maleos are endangered, with only potentially 14,000 individuals left with a rapidly declining population. The reasons for this seem to be due to human exploitation, egg hunting by humans and introduced mammalian predators, and extensive habitat loss. This is also illegal, as much of that lost habitat is protected – as are the eggs of this species, which are being collected in the thousands. Since they are a delicacy, and not a food source staple, this practice must be condemned and hopefully further regulation can help to increase Maleo populations.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut